Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

16 Dec 2022

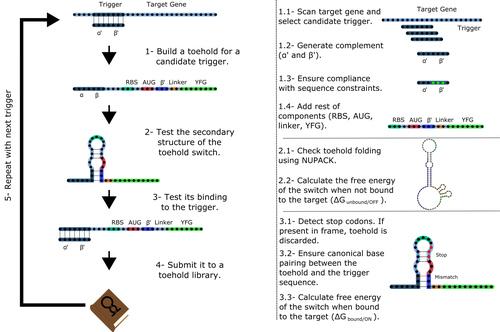

Toeholder: a Software for Automated Design and In Silico Validation of Toehold RiboswitchesAngel F. Cisneros, François D. Rouleau, Carla Bautista, Pascale Lemieux, Nathan Dumont-Leblond https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.09.467922A novel approach for engineering biological systems by interfacing computer science with synthetic biologyRecommended by Sahar Melamed based on reviews by Wim Wranken and 1 anonymous reviewerBiological systems depend on finely tuned interactions of their components. Thus, regulating these components is critical for the system's functionality. In prokaryotic cells, riboswitches are regulatory elements controlling transcription or translation. Riboswitches are RNA molecules that are usually located in the 5′-untranslated region of protein-coding genes. They generate secondary structures leading to the regulation of the expression of the downstream protein-coding gene (Kavita and Breaker, 2022). Riboswitches are very versatile and can bind a wide range of small molecules; in many cases, these are metabolic byproducts from the gene’s enzymatic or signaling pathway. Their versatility and abundance in many species make them attractive for synthetic biological circuits. One class that has been drawing the attention of synthetic biologists is toehold switches (Ekdahl et al., 2022; Green et al., 2014). These are single-stranded RNA molecules harboring the necessary elements for translation initiation of the downstream gene: a ribosome-binding site and a start codon. Conformation change of toehold switches is triggered by an RNA molecule, which enables translation. To exploit the most out of toehold switches, automation of their design would be highly advantageous. Cisneros and colleagues (Cisneros et al., 2022) developed a tool, “Toeholder”, that automates the design of toehold switches and performs in silico tests to select switch candidates for a target gene. Toeholder is an open-source tool that provides a comprehensive and automated workflow for the design of toehold switches. While web tools have been developed for designing toehold switches (To et al., 2018), Toeholder represents an intriguing approach to engineering biological systems by coupling synthetic biology with computational biology. Using molecular dynamics simulations, it identified the positions in the toehold switch where hydrogen bonds fluctuate the most. Identifying these regions holds great potential for modifications when refining the design of the riboswitches. To be effective, toehold switches should provide a strong ON signal and a weak OFF signal in the presence or the absence of a target, respectively. Toeholder nicely ranks the candidate toehold switches based on experimental evidence that correlates with toehold performance (based on good ON/OFF ratios). Riboswitches are highly appealing for a broad range of applications, including pharmaceutical and medical purposes (Blount and Breaker, 2006; Giarimoglou et al., 2022; Tickner and Farzan, 2021), thanks to their adaptability and inexpensiveness. The Toeholder tool developed by Cisneros and colleagues is expected to promote the implementation of toehold switches into these various applications. References Blount KF, Breaker RR (2006) Riboswitches as antibacterial drug targets. Nature Biotechnology, 24, 1558–1564. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt1268 Cisneros AF, Rouleau FD, Bautista C, Lemieux P, Dumont-Leblond N, ULaval 2019 T iGEM (2022) Toeholder: a Software for Automated Design and In Silico Validation of Toehold Riboswitches. bioRxiv, 2021.11.09.467922, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.09.467922 Ekdahl AM, Rojano-Nisimura AM, Contreras LM (2022) Engineering Toehold-Mediated Switches for Native RNA Detection and Regulation in Bacteria. Journal of Molecular Biology, 434, 167689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2022.167689 Giarimoglou N, Kouvela A, Maniatis A, Papakyriakou A, Zhang J, Stamatopoulou V, Stathopoulos C (2022) A Riboswitch-Driven Era of New Antibacterials. Antibiotics, 11, 1243. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11091243 Green AA, Silver PA, Collins JJ, Yin P (2014) Toehold Switches: De-Novo-Designed Regulators of Gene Expression. Cell, 159, 925–939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.002 Kavita K, Breaker RR (2022) Discovering riboswitches: the past and the future. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2022.08.009 Tickner ZJ, Farzan M (2021) Riboswitches for Controlled Expression of Therapeutic Transgenes Delivered by Adeno-Associated Viral Vectors. Pharmaceuticals, 14, 554. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14060554 To AC-Y, Chu DH-T, Wang AR, Li FC-Y, Chiu AW-O, Gao DY, Choi CHJ, Kong S-K, Chan T-F, Chan K-M, Yip KY (2018) A comprehensive web tool for toehold switch design. Bioinformatics, 34, 2862–2864. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty216 | Toeholder: a Software for Automated Design and In Silico Validation of Toehold Riboswitches | Angel F. Cisneros, François D. Rouleau, Carla Bautista, Pascale Lemieux, Nathan Dumont-Leblond | <p>Abstract: Synthetic biology aims to engineer biological circuits, which often involve gene expression. A particularly promising group of regulatory elements are riboswitches because of their versatility with respect to their targets, but e... |  | Bioinformatics | Sahar Melamed | 2022-02-16 14:40:13 | View | |

15 Dec 2022

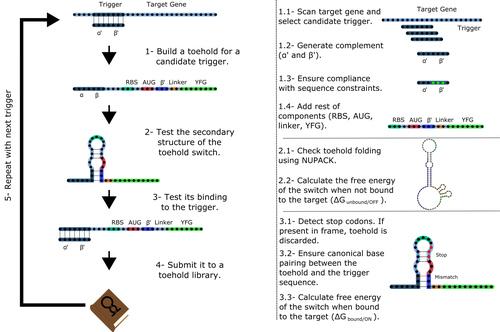

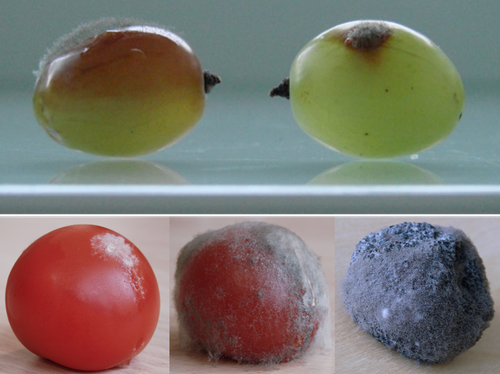

Botrytis cinerea strains infecting grapevine and tomato display contrasted repertoires of accessory chromosomes, transposons and small RNAsAdeline Simon, Alex Mercier, Pierre Gladieux, Benoit Poinssot, Anne-Sophie Walker, Muriel Viaud https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.07.483234Exploring genomic determinants of host specialization in Botrytis cinereaRecommended by Sebastien Duplessis based on reviews by Cecile Lorrain and Thorsten LangnerThe genomics era has pushed forward our understanding of fungal biology. Much progress has been made in unraveling new gene functions and pathways, as well as the evolution or adaptation of fungi to their hosts or environments through population studies (Hartmann et al. 2019; Gladieux et al. 2018). Closing gaps more systematically in draft genomes using the most recent long-read technologies now seems the new standard, even with fungal species presenting complex genome structures (e.g. large and highly repetitive dikaryotic genomes; Duan et al. 2022). Understanding the genomic dynamics underlying host specialization in phytopathogenic fungi is of utmost importance as it may open new avenues to combat diseases. A strong host specialization is commonly observed for biotrophic and hemi-biotrophic fungal species or for necrotrophic fungi with a narrow host range, whereas necrotrophic fungi with broad host range are considered generalists (Liang and Rollins, 2018; Newman and Derbyshire, 2020). However, some degrees of specialization towards given hosts have been reported in generalist fungi and the underlying mechanisms remain to be determined. Botrytis cinerea is a polyphagous necrotrophic phytopathogen with a particularly wide host range and it is notably responsible for grey mould disease on many fruits, such as tomato and grapevine. Because of its importance as a plant pathogen, its relatively small genome size and its taxonomical position, it has been targeted for early genome sequencing and a first reference genome was provided in 2011 (Amselem et al. 2011). Other genomes were subsequently sequenced for other strains, and most importantly a gapless assembled version of the initial reference genome B05.10 was provided to the community (van Kan et al. 2017). This genomic resource has supported advances in various aspects of the biology of B. cinerea such as the production of specialized metabolites, which plays an important role in host-plant colonization, or more recently in the production of small RNAs which interfere with the host immune system, representing a new class of non-proteinaceous virulence effectors (Dalmais et al. 2011; Weiberg et al. 2013). In the present study, Simon et al. (2022) use PacBio long-read sequencing for Sl3 and Vv3 strains, which represent genetic clusters in B. cinerea populations found on tomato and grapevine. The authors combined these complete and high-quality genome assemblies with the B05.10 reference genome and population sequencing data to perform a comparative genomic analysis of specialization towards the two host plants. Transposable elements generate genomic diversity due to their mobile and repetitive nature and they are of utmost importance in the evolution of fungi as they deeply reshape the genomic landscape (Lorrain et al. 2021). Accessory chromosomes are also known drivers of adaptation in fungi (Möller and Stukenbrock, 2017). Here, the authors identify several genomic features such as the presence of different sets of accessory chromosomes, the presence of differentiated repertoires of transposable elements, as well as related small RNAs in the tomato and grapevine populations, all of which may be involved in host specialization. Whereas core chromosomes are highly syntenic between strains, an accessory chromosome validated by pulse-field electrophoresis is specific of the strains isolated from grapevine. Particularly, they show that two particular retrotransposons are discriminant between the strains and that they allow the production of small RNAs that may act as effectors. The discriminant accessory chromosome of the Vv3 strain harbors one of the unraveled retrotransposons as well as new genes of yet unidentified function. I recommend this article because it perfectly illustrates how efforts put into generating reference genomic sequences of higher quality can lead to new discoveries and allow to build strong hypotheses about biology and evolution in fungi. Also, the study combines an up-to-date genomics approach with a classical methodology such as pulse-field electrophoresis to validate the presence of accessory chromosomes. A major input of this investigation of the genomic determinants of B. cinerea is that it provides solid hints for further analysis of host-specialization at the population level in a broad-scale phytopathogenic fungus. References Amselem J, Cuomo CA, Kan JAL van, Viaud M, Benito EP, Couloux A, Coutinho PM, Vries RP de, Dyer PS, Fillinger S, Fournier E, Gout L, Hahn M, Kohn L, Lapalu N, Plummer KM, Pradier J-M, Quévillon E, Sharon A, Simon A, Have A ten, Tudzynski B, Tudzynski P, Wincker P, Andrew M, Anthouard V, Beever RE, Beffa R, Benoit I, Bouzid O, Brault B, Chen Z, Choquer M, Collémare J, Cotton P, Danchin EG, Silva CD, Gautier A, Giraud C, Giraud T, Gonzalez C, Grossetete S, Güldener U, Henrissat B, Howlett BJ, Kodira C, Kretschmer M, Lappartient A, Leroch M, Levis C, Mauceli E, Neuvéglise C, Oeser B, Pearson M, Poulain J, Poussereau N, Quesneville H, Rascle C, Schumacher J, Ségurens B, Sexton A, Silva E, Sirven C, Soanes DM, Talbot NJ, Templeton M, Yandava C, Yarden O, Zeng Q, Rollins JA, Lebrun M-H, Dickman M (2011) Genomic Analysis of the Necrotrophic Fungal Pathogens Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and Botrytis cinerea. PLOS Genetics, 7, e1002230. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002230 Dalmais B, Schumacher J, Moraga J, Le Pêcheur P, Tudzynski B, Collado IG, Viaud M (2011) The Botrytis cinerea phytotoxin botcinic acid requires two polyketide synthases for production and has a redundant role in virulence with botrydial. Molecular Plant Pathology, 12, 564–579. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1364-3703.2010.00692.x Duan H, Jones AW, Hewitt T, Mackenzie A, Hu Y, Sharp A, Lewis D, Mago R, Upadhyaya NM, Rathjen JP, Stone EA, Schwessinger B, Figueroa M, Dodds PN, Periyannan S, Sperschneider J (2022) Physical separation of haplotypes in dikaryons allows benchmarking of phasing accuracy in Nanopore and HiFi assemblies with Hi-C data. Genome Biology, 23, 84. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-022-02658-2 Gladieux P, Condon B, Ravel S, Soanes D, Maciel JLN, Nhani A, Chen L, Terauchi R, Lebrun M-H, Tharreau D, Mitchell T, Pedley KF, Valent B, Talbot NJ, Farman M, Fournier E (2018) Gene Flow between Divergent Cereal- and Grass-Specific Lineages of the Rice Blast Fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. mBio, 9, e01219-17. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.01219-17 Hartmann FE, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, Carpentier F, Gladieux P, Cornille A, Hood ME, Giraud T (2019) Understanding Adaptation, Coevolution, Host Specialization, and Mating System in Castrating Anther-Smut Fungi by Combining Population and Comparative Genomics. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 57, 431–457. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-phyto-082718-095947 Liang X, Rollins JA (2018) Mechanisms of Broad Host Range Necrotrophic Pathogenesis in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Phytopathology®, 108, 1128–1140. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-06-18-0197-RVW Lorrain C, Oggenfuss U, Croll D, Duplessis S, Stukenbrock E (2021) Transposable Elements in Fungi: Coevolution With the Host Genome Shapes, Genome Architecture, Plasticity and Adaptation. In: Encyclopedia of Mycology (eds Zaragoza Ó, Casadevall A), pp. 142–155. Elsevier, Oxford. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-819990-9.00042-1 Möller M, Stukenbrock EH (2017) Evolution and genome architecture in fungal plant pathogens. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 15, 756–771. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2017.76 Newman TE, Derbyshire MC (2020) The Evolutionary and Molecular Features of Broad Host-Range Necrotrophy in Plant Pathogenic Fungi. Frontiers in Plant Science, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.591733 Simon A, Mercier A, Gladieux P, Poinssot B, Walker A-S, Viaud M (2022) Botrytis cinerea strains infecting grapevine and tomato display contrasted repertoires of accessory chromosomes, transposons and small RNAs. bioRxiv, 2022.03.07.483234, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.07.483234 Van Kan JAL, Stassen JHM, Mosbach A, Van Der Lee TAJ, Faino L, Farmer AD, Papasotiriou DG, Zhou S, Seidl MF, Cottam E, Edel D, Hahn M, Schwartz DC, Dietrich RA, Widdison S, Scalliet G (2017) A gapless genome sequence of the fungus Botrytis cinerea. Molecular Plant Pathology, 18, 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/mpp.12384 Weiberg A, Wang M, Lin F-M, Zhao H, Zhang Z, Kaloshian I, Huang H-D, Jin H (2013) Fungal Small RNAs Suppress Plant Immunity by Hijacking Host RNA Interference Pathways. Science, 342, 118–123. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1239705 | Botrytis cinerea strains infecting grapevine and tomato display contrasted repertoires of accessory chromosomes, transposons and small RNAs | Adeline Simon, Alex Mercier, Pierre Gladieux, Benoit Poinssot, Anne-Sophie Walker, Muriel Viaud | <p style="text-align: justify;">The fungus <em>Botrytis cinerea</em> is a polyphagous pathogen that encompasses multiple host-specialized lineages. While several secreted proteins, secondary metabolites and retrotransposons-derived small RNAs have... |  | Fungi, Structural genomics, Viruses and transposable elements | Sebastien Duplessis | Cecile Lorrain, Thorsten Langner | 2022-03-15 11:15:48 | View |

25 Nov 2022

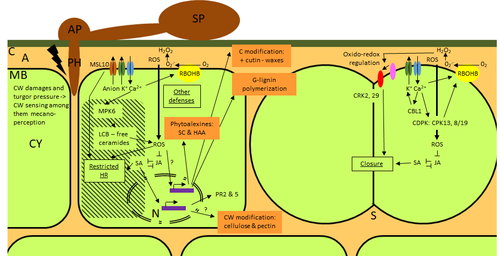

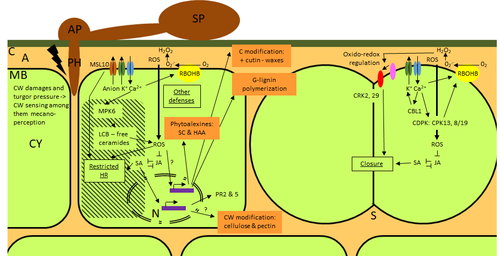

Phenotypic and transcriptomic analyses reveal major differences between apple and pear scab nonhost resistanceE. Vergne, E. Chevreau, E. Ravon, S. Gaillard, S. Pelletier, M. Bahut, L. Perchepied https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.01.446506Apples and pears: two closely related species with differences in scab nonhost resistanceRecommended by Wirulda Pootakham based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersNonhost resistance is a common form of disease resistance exhibited by plants against microorganisms that are pathogenic to other plant species [1]. Apples and pears are two closely related species belonging to Rosaceae family, both affected by scab disease caused by fungal pathogens in the Venturia genus. These pathogens appear to be highly host-specific. While apples are nonhosts for Venturia pyrina, pears are nonhosts for Venturia inaequalis. To date, the molecular bases of scab nonhost resistance in apple and pear have not been elucidated. This preprint by Vergne, et al (2022) [2] analyzed nonhost resistance symptoms in apple/V. pyrina and pear/V. inaequalis interactions as well as their transcriptomic responses. Interestingly, the author demonstrated that the nonhost apple/V. pyrina interaction was almost symptomless while hypersensitive reactions were observed for pear/V. inaequalis interaction. The transcriptomic analyses also revealed a number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) that corresponded to the severity of the interactions, with very few DEGs observed during the apple/V. pyrina interaction and a much higher number of DEGs during the pear/V. inaequalis interaction. This type of reciprocal host-pathogen interaction study is valuable in gaining new insights into how plants interact with microorganisms that are potential pathogens in related species. A few processes appeared to be involved in the pear resistance against the nonhost pathogen V. inaequalis at the transcriptomic level, such as stomata closure, modification of cell wall and production of secondary metabolites as well as phenylpropanoids. Based on the transcriptomics changes during the nonhost interaction, the author compared the responses to those of host-pathogen interactions and revealed some interesting findings. They proposed a series of cascading effects in pear induced by the presence of V. inaequalis, which I believe helps shed some light on the basic mechanism for nonhost resistance. I am recommending this study because it provides valuable information that will strengthen our understanding of nonhost resistance in the Rosaceae family and other plant species. The knowledge gained here may be applied to genetically engineer plants for a broader resistance against a number of pathogens in the future. References 1. Senthil-Kumar M, Mysore KS (2013) Nonhost Resistance Against Bacterial Pathogens: Retrospectives and Prospects. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 51, 407–427. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-phyto-082712-102319 2. Vergne E, Chevreau E, Ravon E, Gaillard S, Pelletier S, Bahut M, Perchepied L (2022) Phenotypic and transcriptomic analyses reveal major differences between apple and pear scab nonhost resistance. bioRxiv, 2021.06.01.446506, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.01.446506 | Phenotypic and transcriptomic analyses reveal major differences between apple and pear scab nonhost resistance | E. Vergne, E. Chevreau, E. Ravon, S. Gaillard, S. Pelletier, M. Bahut, L. Perchepied | <p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>Background. </strong>Nonhost resistance is the outcome of most plant/pathogen interactions, but it has rarely been described in Rosaceous fruit species. Apple (<em>Malus x domestica</em> Borkh.) have a nonho... |  | Functional genomics, Plants | Wirulda Pootakham | Jessica Soyer, Anonymous | 2022-05-13 15:06:08 | View |

08 Nov 2022

Somatic mutation detection: a critical evaluation through simulations and reanalyses in oaksSylvain Schmitt, Thibault Leroy, Myriam Heuertz, Niklas Tysklind https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.11.462798How to best call the somatic mosaic tree?Recommended by Nicolas Bierne based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersAny multicellular organism is a molecular mosaic with some somatic mutations accumulated between cell lineages. Big long-lived trees have nourished this imaginary of a somatic mosaic tree, from the observation of spectacular phenotypic mosaics and also because somatic mutations are expected to potentially be passed on to gametes in plants (review in Schoen and Schultz 2019). The lower cost of genome sequencing now offers the opportunity to tackle the issue and identify somatic mutations in trees. However, when it comes to characterizing this somatic mosaic from genome sequences, things become much more difficult than one would think in the first place. What separates cell lineages ontogenetically, in cell division number, or in time? How to sample clonal cell populations? How do somatic mutations distribute in a population of cells in an organ or an organ sample? Should they be fixed heterozygotes in the sample of cells sequenced or be polymorphic? Do we indeed expect somatic mutations to be fixed? How should we identify and count somatic mutations? To date, the detection of somatic mutations has mostly been done with a single variant caller in a given study, and we have little perspective on how different callers provide similar or different results. Some studies have used standard SNP callers that assumed a somatic mutation is fixed at the heterozygous state in the sample of cells, with an expected allele coverage ratio of 0.5, and less have used cancer callers, designed to detect mutations in a fraction of the cells in the sample. However, standard SNP callers detect mutations that deviate from a balanced allelic coverage, and different cancer callers can have different characteristics that should affect their outcomes. In order to tackle these issues, Schmitt et al. (2022) conducted an extensive simulation analysis to compare different variant callers. Then, they reanalyzed two large published datasets on pedunculate oak, Quercus robur. The analysis of in silico somatic mutations allowed the authors to evaluate the performance of different variant callers as a function of the allelic fraction of somatic mutations and the sequencing depth. They found one of the seven callers to provide better and more robust calls for a broad set of allelic fractions and sequencing depths. The reanalysis of published datasets in oaks with the most effective cancer caller of the in silico analysis allowed them to identify numerous low-frequency mutations that were missed in the original studies. I recommend the study of Schmitt et al. (2022) first because it shows the benefit of using cancer callers in the study of somatic mutations, whatever the allelic fraction you are interested in at the end. You can select fixed heterozygotes if this is your ultimate target, but cancer callers allow you to have in addition a valuable overview of the allelic fractions of somatic mutations in your sample, and most do as well as SNP callers for fixed heterozygous mutations. In addition, Schmitt et al. (2022) provide the pipelines that allow investigating in silico data that should correspond to a given study design, encouraging to compare different variant callers rather than arbitrarily going with only one. We can anticipate that the study of somatic mutations in non-model species will increasingly attract attention now that multiple tissues of the same individual can be sequenced at low cost, and the study of Schmitt et al. (2022) paves the way for questioning and choosing the best variant caller for the question one wants to address. References Schoen DJ, Schultz ST (2019) Somatic Mutation and Evolution in Plants. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 50, 49–73. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110218-024955 Schmitt S, Leroy T, Heuertz M, Tysklind N (2022) Somatic mutation detection: a critical evaluation through simulations and reanalyses in oaks. bioRxiv, 2021.10.11.462798. ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.11.462798 | Somatic mutation detection: a critical evaluation through simulations and reanalyses in oaks | Sylvain Schmitt, Thibault Leroy, Myriam Heuertz, Niklas Tysklind | <p style="text-align: justify;">1. Mutation, the source of genetic diversity, is the raw material of evolution; however, the mutation process remains understudied, especially in plants. Using both a simulation and reanalysis framework, we set out ... |  | Bioinformatics, Plants | Nicolas Bierne | Anonymous, Anonymous | 2022-04-28 13:24:19 | View |

23 Sep 2022

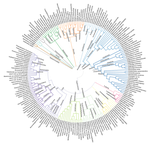

MATEdb, a data repository of high-quality metazoan transcriptome assemblies to accelerate phylogenomic studiesRosa Fernandez, Vanina Tonzo, Carolina Simon Guerrero, Jesus Lozano-Fernandez, Gemma I Martinez-Redondo, Pau Balart-Garcia, Leandro Aristide, Klara Eleftheriadi, Carlos Vargas-Chavez https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.18.500182MATEdb: a new phylogenomic-driven database for MetazoaRecommended by Samuel Abalde based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

The development (and standardization) of high-throughput sequencing techniques has revolutionized evolutionary biology, to the point that we almost see as normal fine-detail studies of genome architecture evolution (Robert et al., 2022), adaptation to new habitats (Rahi et al., 2019), or the development of key evolutionary novelties (Hilgers et al., 2018), to name three examples. One of the fields that has benefited the most is phylogenomics, i.e. the use of genome-wide data for inferring the evolutionary relationships among organisms. Dealing with such amount of data, however, has come with important analytical and computational challenges. Likewise, although the steady generation of genomic data from virtually any organism opens exciting opportunities for comparative analyses, it also creates a sort of “information fog”, where it is hard to find the most appropriate and/or the higher quality data. I have personally experienced this not so long ago, when I had to spend several weeks selecting the most complete transcriptomes from several phyla, moving back and forth between the NCBI SRA repository and the relevant literature. In an attempt to deal with this issue, some research labs have committed their time and resources to the generation of taxa- and topic-specific databases (Lathe et al., 2008), such as MolluscDB (Liu et al., 2021), focused on mollusk genomics, or EukProt (Richter et al., 2022), a protein repository representing the diversity of eukaryotes. A new database that promises to become an important resource in the near future is MATEdb (Fernández et al., 2022), a repository of high-quality genomic data from Metazoa. MATEdb has been developed from publicly available and newly generated transcriptomes and genomes, prioritizing quality over quantity. Upon download, the user has access to both raw data and the related datasets: assemblies, several quality metrics, the set of inferred protein-coding genes, and their annotation. Although it is clear to me that this repository has been created with phylogenomic analyses in mind, I see how it could be generalized to other related problems such as analyses of gene content or evolution of specific gene families. In my opinion, the main strengths of MATEdb are threefold:

On a negative note, I see two main drawbacks. First, as of today (September 16th, 2022) this database is in an early stage and it still needs to incorporate a lot of animal groups. This has been discussed during the revision process and the authors are already working on it, so it is only a matter of time until all major taxa are represented. Second, there is a scalability issue. In its current format it is not possible to select the taxa of interest and the full database has to be downloaded, which will become more and more difficult as it grows. Nonetheless, with the appropriate resources it would be easy to find a better solution. There are plenty of examples that could serve as inspiration, so I hope this does not become a big problem in the future. Altogether, I and the researchers that participated in the revision process believe that MATEdb has the potential to become an important and valuable addition to the metazoan phylogenomics community. Personally, I wish it was available just a few months ago, it would have saved me so much time. References Fernández R, Tonzo V, Guerrero CS, Lozano-Fernandez J, Martínez-Redondo GI, Balart-García P, Aristide L, Eleftheriadi K, Vargas-Chávez C (2022) MATEdb, a data repository of high-quality metazoan transcriptome assemblies to accelerate phylogenomic studies. bioRxiv, 2022.07.18.500182, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.18.500182 Hilgers L, Hartmann S, Hofreiter M, von Rintelen T (2018) Novel Genes, Ancient Genes, and Gene Co-Option Contributed to the Genetic Basis of the Radula, a Molluscan Innovation. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 35, 1638–1652. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy052 Lathe W, Williams J, Mangan M, Karolchik, D (2008). Genomic data resources: challenges and promises. Nature Education, 1(3), 2. Liu F, Li Y, Yu H, Zhang L, Hu J, Bao Z, Wang S (2021) MolluscDB: an integrated functional and evolutionary genomics database for the hyper-diverse animal phylum Mollusca. Nucleic Acids Research, 49, D988–D997. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa918 Rahi ML, Mather PB, Ezaz T, Hurwood DA (2019) The Molecular Basis of Freshwater Adaptation in Prawns: Insights from Comparative Transcriptomics of Three Macrobrachium Species. Genome Biology and Evolution, 11, 1002–1018. https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evz045 Richter DJ, Berney C, Strassert JFH, Poh Y-P, Herman EK, Muñoz-Gómez SA, Wideman JG, Burki F, Vargas C de (2022) EukProt: A database of genome-scale predicted proteins across the diversity of eukaryotes. bioRxiv, 2020.06.30.180687, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.30.180687 Robert NSM, Sarigol F, Zimmermann B, Meyer A, Voolstra CR, Simakov O (2022) Emergence of distinct syntenic density regimes is associated with early metazoan genomic transitions. BMC Genomics, 23, 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-022-08304-2 | MATEdb, a data repository of high-quality metazoan transcriptome assemblies to accelerate phylogenomic studies | Rosa Fernandez, Vanina Tonzo, Carolina Simon Guerrero, Jesus Lozano-Fernandez, Gemma I Martinez-Redondo, Pau Balart-Garcia, Leandro Aristide, Klara Eleftheriadi, Carlos Vargas-Chavez | <p style="text-align: justify;">With the advent of high throughput sequencing, the amount of genomic data available for animals (Metazoa) species has bloomed over the last decade, especially from transcriptomes due to lower sequencing costs and ea... |  | Bioinformatics, Evolutionary genomics, Functional genomics | Samuel Abalde | 2022-07-20 07:30:39 | View | |

15 Sep 2022

EukProt: A database of genome-scale predicted proteins across the diversity of eukaryotesDaniel J. Richter, Cédric Berney, Jürgen F. H. Strassert, Yu-Ping Poh, Emily K. Herman, Sergio A. Muñoz-Gómez, Jeremy G. Wideman, Fabien Burki, Colomban de Vargas https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.30.180687EukProt enables reproducible Eukaryota-wide protein sequence analysesRecommended by Gavin Douglas based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Comparative genomics is a general approach for understanding how genomes differ, which can be considered from many angles. For instance, this approach can delineate how gene content varies across organisms, which can lead to novel hypotheses regarding what those organisms do. It also enables investigations into the sequence-level divergence of orthologous DNA, which can provide insight into how evolutionary forces differentially shape genome content and structure across lineages. Burki F, Roger AJ, Brown MW, Simpson AGB (2020) The New Tree of Eukaryotes. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 35, 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2019.08.008 Richter DJ, Berney C, Strassert JFH, Poh Y-P, Herman EK, Muñoz-Gómez SA, Wideman JG, Burki F, Vargas C de (2022) EukProt: A database of genome-scale predicted proteins across the diversity of eukaryotes. bioRxiv, 2020.06.30.180687, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.30.180687 Wilkinson MD, Dumontier M, Aalbersberg IjJ, Appleton G, Axton M, Baak A, Blomberg N, Boiten J-W, da Silva Santos LB, Bourne PE, Bouwman J, Brookes AJ, Clark T, Crosas M, Dillo I, Dumon O, Edmunds S, Evelo CT, Finkers R, Gonzalez-Beltran A, Gray AJG, Groth P, Goble C, Grethe JS, Heringa J, ’t Hoen PAC, Hooft R, Kuhn T, Kok R, Kok J, Lusher SJ, Martone ME, Mons A, Packer AL, Persson B, Rocca-Serra P, Roos M, van Schaik R, Sansone S-A, Schultes E, Sengstag T, Slater T, Strawn G, Swertz MA, Thompson M, van der Lei J, van Mulligen E, Velterop J, Waagmeester A, Wittenburg P, Wolstencroft K, Zhao J, Mons B (2016) The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data, 3, 160018. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18 | EukProt: A database of genome-scale predicted proteins across the diversity of eukaryotes | Daniel J. Richter, Cédric Berney, Jürgen F. H. Strassert, Yu-Ping Poh, Emily K. Herman, Sergio A. Muñoz-Gómez, Jeremy G. Wideman, Fabien Burki, Colomban de Vargas | <p style="text-align: justify;">EukProt is a database of published and publicly available predicted protein sets selected to represent the breadth of eukaryotic diversity, currently including 993 species from all major supergroups as well as orpha... |  | Bioinformatics, Evolutionary genomics | Gavin Douglas | 2022-06-08 14:19:28 | View | |

23 Aug 2022

A novel lineage of the Capra genus discovered in the Taurus Mountains of Turkey using ancient genomicsKevin G. Daly, Benjamin S. Arbuckle, Conor Rossi, Valeria Mattiangeli, Phoebe A. Lawlor, Marjan Mashkour, Eberhard Sauer, Joséphine Lesur, Levent Atici, Cevdet Merih Erek, Daniel G. Bradley https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.08.487619Goat ancient DNA analysis unveils a new lineage that may have hybridized with domestic goatsRecommended by Laura Botigué based on reviews by Torsten Günther and 1 anonymous reviewerThe genomic analysis of ancient remains has revolutionized the study of the past over the last decade. On top of the discoveries related to human evolution, plant and animal archaeogenomics has been used to gain new insights into the domestication process and the dispersal of domestic forms. In this study, Daly and colleagues analyse the genomic data from seven goat specimens from the Epipalaeolithic recovered from the Direkli Cave in the Taurus Mountains in southern Turkey. They also generate new genomic data from Capra lineages across the phylogeny, contributing to the availability of genomic resources for this genus. Analysis of the ancient remains is compared to modern genomic variability and sheds light on the complexity of the Tur wild Capra lineages and their relationship with domestic goats and their wild ancestors. Authors find that during the Late Pleistocene in the Taurus Mountains wild goats from the Tur lineage, today restricted to the Caucasus region, were not rare and cohabited with Bezoar, the wild goats that are the ancestors of domestic goats. They identify the Direkli Cave specimens as a lineage separate from the A modified D statistic, Dex, is developed to examine the contribution of the ancient Tur lineage in domestic goats through time and space. Dex measures the relative degree of allele sharing, derived specifically in a selected genome or group of genomes, and may have some utility in genera with complex admixture histories or admixture from ghost lineages. Results confirm that Neolithic European goat had an excess of allele sharing with this ancient Tur lineage, something that is absent in contemporary goats eastwards or in modern goats. Interspecific gene flow is not uncommon among mammals, but the case of Capra has the additional motivation of understanding the origins of the domestic species. This work uncovers an ancient Tur lineage that is different from the modern ones and is additionally found in another geographic area. Furthermore, evidence shows that this ancient lineage exhibits substantial amounts of allele sharing with the wild ancestor of the domestic goat, but also with the Neolithic Eurasian domestic goats, highlighting the complexity of the domestication process. This work has also important implications in understanding the effect of over-hunting and habitat disruption during the Anthropocene on the evolution of the Capra genus. The availability of more ancient specimens and better coverage of the modern genomic variability can help quantifying the lineages that went lost and identify the causes of their extinction. This work is limited by the current availability of whole genomes from modern Capra specimens, but pieces of evidence as well that an effort is needed to obtain more genomic data from ancient goats from different geographic ranges to determine to what extent these lineages contributed to goat domestication. References Daly KG, Arbuckle BS, Rossi C, Mattiangeli V, Lawlor PA, Mashkour M, Sauer E, Lesur J, Atici L, Cevdet CM and Bradley DG (2022) A novel lineage of the Capra genus discovered in the Taurus Mountains of Turkey using ancient genomics. bioRxiv, 2022.04.08.487619, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.08.487619 | A novel lineage of the Capra genus discovered in the Taurus Mountains of Turkey using ancient genomics | Kevin G. Daly, Benjamin S. Arbuckle, Conor Rossi, Valeria Mattiangeli, Phoebe A. Lawlor, Marjan Mashkour, Eberhard Sauer, Joséphine Lesur, Levent Atici, Cevdet Merih Erek, Daniel G. Bradley | <p>Direkli Cave, located in the Taurus Mountains of southern Turkey, was occupied by Late Epipaleolithic hunters-gatherers for the seasonal hunting and processing of game including large numbers of wild goats. We report genomic data from new and p... |  | Evolutionary genomics, Population genomics, Vertebrates | Laura Botigué | 2022-04-15 12:05:47 | View | |

18 Jul 2022

CulebrONT: a streamlined long reads multi-assembler pipeline for prokaryotic and eukaryotic genomesJulie Orjuela, Aurore Comte, Sébastien Ravel, Florian Charriat, Tram Vi, Francois Sabot, Sébastien Cunnac https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.19.452922A flexible and reproducible pipeline for long-read assembly and evaluationRecommended by Raúl Castanera based on reviews by Benjamin Istace and Valentine MurigneuxThird-generation sequencing has revolutionised de novo genome assembly. Thanks to this technology, genome reference sequences have evolved from fragmented drafts to gapless, telomere-to-telomere genome assemblies. Long reads produced by Oxford Nanopore and PacBio technologies can span structural variants and resolve complex repetitive regions such as centromeres, unlocking previously inaccessible genomic information. Nowadays, many research groups can afford to sequence the genome of their working model using long reads. Nevertheless, genome assembly poses a significant computational challenge. Read length, quality, coverage and genomic features such as repeat content can affect assembly contiguity, accuracy, and completeness in almost unpredictable ways. Consequently, there is no best universal software or protocol for this task. Producing a high-quality assembly requires chaining several tools into pipelines and performing extensive comparisons between the assemblies obtained by different tool combinations to decide which one is the best. This task can be extremely challenging, as the number of tools available rises very rapidly, and thorough benchmarks cannot be updated and published at such a fast pace. In their paper, Orjuela and collaborators present CulebrONT [1], a universal pipeline that greatly contributes to overcoming these challenges and facilitates long-read genome assembly for all taxonomic groups. CulebrONT incorporates six commonly used assemblers and allows to perform assembly, circularization (if needed), polishing, and evaluation in a simple framework. One important aspect of CulebrONT is its modularity, which allows the activation or deactivation of specific tools, giving great flexibility to the user. Nevertheless, possibly the best feature of CulebrONT is the opportunity to benchmark the selected tool combinations based on the excellent report generated by the pipeline. This HTML report aggregates the output of several tools for quality evaluation of the assemblies (e.g. BUSCO [2] or QUAST [3]) generated by the different assemblers, in addition to the running time and configuration parameters. Such information is of great help to identify the best-suited pipeline, as exemplified by the authors using four datasets of different taxonomic origins. Finally, CulebrONT can handle multiple samples in parallel, which makes it a good solution for laboratories looking for multiple assemblies on a large scale. References 1. Orjuela J, Comte A, Ravel S, Charriat F, Vi T, Sabot F, Cunnac S (2022) CulebrONT: a streamlined long reads multi-assembler pipeline for prokaryotic and eukaryotic genomes. bioRxiv, 2021.07.19.452922, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.19.452922 2. Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM (2015) BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics, 31, 3210–3212. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351 3. Gurevich A, Saveliev V, Vyahhi N, Tesler G (2013) QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics, 29, 1072–1075. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086 | CulebrONT: a streamlined long reads multi-assembler pipeline for prokaryotic and eukaryotic genomes | Julie Orjuela, Aurore Comte, Sébastien Ravel, Florian Charriat, Tram Vi, Francois Sabot, Sébastien Cunnac | <p style="text-align: justify;">Using long reads provides higher contiguity and better genome assemblies. However, producing such high quality sequences from raw reads requires to chain a growing set of tools, and determining the best workflow is ... |  | Bioinformatics | Raúl Castanera | Valentine Murigneux | 2022-02-22 16:21:25 | View |

13 Jul 2022

Nucleosome patterns in four plant pathogenic fungi with contrasted genome structuresColin Clairet, Nicolas Lapalu, Adeline Simon, Jessica L. Soyer, Muriel Viaud, Enric Zehraoui, Berengere Dalmais, Isabelle Fudal, Nadia Ponts https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.16.439968Genome-wide chromatin and expression datasets of various pathogenic ascomycetesRecommended by Sébastien Bloyer and Romain Koszul based on reviews by Ricardo C. Rodríguez de la Vega and 1 anonymous reviewerPlant pathogenic fungi represent serious economic threats. These organisms are rapidly adaptable, with plastic genomes containing many variable regions and evolving rapidly. It is, therefore, useful to characterize their genetic regulation in order to improve their control. One of the steps to do this is to obtain omics data that link their DNA structure and gene expression. Clairet C, Lapalu N, Simon A, Soyer JL, Viaud M, Zehraoui E, Dalmais B, Fudal I, Ponts N (2022) Nucleosome patterns in four plant pathogenic fungi with contrasted genome structures. bioRxiv, 2021.04.16.439968, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.16.439968 | Nucleosome patterns in four plant pathogenic fungi with contrasted genome structures | Colin Clairet, Nicolas Lapalu, Adeline Simon, Jessica L. Soyer, Muriel Viaud, Enric Zehraoui, Berengere Dalmais, Isabelle Fudal, Nadia Ponts | <p style="text-align: justify;">Fungal pathogens represent a serious threat towards agriculture, health, and environment. Control of fungal diseases on crops necessitates a global understanding of fungal pathogenicity determinants and their expres... |  | Epigenomics, Fungi | Sébastien Bloyer | 2021-04-17 10:32:41 | View | |

13 Jul 2022

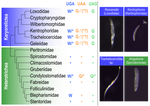

Karyorelict ciliates use an ambiguous genetic code with context-dependent stop/sense codonsBrandon Kwee Boon Seah, Aditi Singh, Estienne Carl Swart https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.12.488043An accident frozen in time: the ambiguous stop/sense genetic code of karyorelict ciliatesRecommended by Iker Irisarri based on reviews by Vittorio Boscaro and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Vittorio Boscaro and 2 anonymous reviewers

Several variations of the “universal” genetic code are known. Among the most striking are those where a codon can either encode for an amino acid or a stop signal depending on the context. Such ambiguous codes are known to have evolved in eukaryotes multiple times independently, particularly in ciliates – eight different codes have so far been discovered (1). We generally view such genetic codes are rare ‘variants’ of the standard code restricted to single species or strains, but this might as well reflect a lack of study of closely related species. In this study, Seah and co-authors (2) explore the possibility of codon reassignment in karyorelict ciliates closely related to Parduczia sp., which has been shown to contain an ambiguous genetic code (1). Here, single-cell transcriptomics are used, along with similar available data, to explore the possibility of codon reassignment across the diversity of Karyorelictea (four out of the six recognized families). Codon reassignments were inferred from their frequencies within conserved Pfam (3) protein domains, whereas stop codons were inferred from full-length transcripts with intact 3’-UTRs. Results show the reassignment of UAA and UAG stop codons to code for glutamine (Q) and the reassignment of the UGA stop codon into tryptophan (W). This occurs only within the coding sequences, whereas the end of transcription is marked by UGA as the main stop codon, and to a lesser extent by UAA. In agreement with a previous model proposed that explains the functioning of ambiguous codes (1,4), the authors observe a depletion of in-frame UGAs before the UGA codon that indicates the stop, thus avoiding premature termination of transcription. The inferred codon reassignments occur in all studied karyorelicts, including the previously studied Parduczia sp. Despite the overall clear picture, some questions remain. Data for two out of six main karyorelict lineages are so far absent and the available data for Cryptopharyngidae was inconclusive; the phylogenetic affinities of Cryptopharyngidae have also been questioned (5). This indicates the need for further study of this interesting group of organisms. As nicely discussed by the authors, experimental evidence could further strengthen the conclusions of this paper, including ribosome profiling, mass spectrometry – as done for Condylostoma (1) – or even direct genetic manipulation. The uniformity of the ambiguous genetic code across karyorelicts might at first seem dull, but when viewed in a phylogenetic context character distribution strongly suggest that this genetic code has an ancient origin in the karyorelict ancestor ~455 Ma in the Proterozoic (6). This ambiguous code is also not a rarity of some obscure species, but it is shared by ciliates that are very diverse and ecologically important. The origin of the karyorelict code is also intriguing. Adaptive arguments suggest that it could confer robustness to mutations causing premature stop codons. However, we lack evidence for ambiguous codes being linked to specific habitats of lifestyles that could account for it. Instead, the authors favor the neutral view of an ancient “frozen accident”, fixed stochastically simply because it did not pose a significant selective disadvantage. Once a stop codon is reassigned to an amino acid, it is increasingly difficult to revert this without the deleterious effect of prematurely terminating translation. At the end, the origin of the genetic code itself is thought to be a frozen accident too (7). References 1. Swart EC, Serra V, Petroni G, Nowacki M. Genetic codes with no dedicated stop codon: Context-dependent translation termination. Cell 2016;166: 691–702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.020 2. Seah BKB, Singh A, Swart EC (2022) Karyorelict ciliates use an ambiguous genetic code with context-dependent stop/sense codons. bioRxiv, 2022.04.12.488043. ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.12.488043 3. Mistry J, Chuguransky S, Williams L, Qureshi M, Salazar GA, Sonnhammer ELL, Tosatto SCE, Paladin L, Raj S, Richardson LJ, Finn RD, Bateman A. Pfam: The protein families database in 2021, Nuc Acids Res 2020;49: D412-D419. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa913 4. Alkalaeva E, Mikhailova T. Reassigning stop codons via translation termination: How a few eukaryotes broke the dogma. Bioessays. 2017;39. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.201600213 5. Xu Y, Li J, Song W, Warren A. Phylogeny and establishment of a new ciliate family, Wilbertomorphidae fam. nov. (Ciliophora, Karyorelictea), a highly specialized taxon represented by Wilbertomorpha colpoda gen. nov., spec. nov. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2013;60: 480–489. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeu.12055 6. Fernandes NM, Schrago CG. A multigene timescale and diversification dynamics of Ciliophora evolution. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2019;139: 106521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2019.106521 7. Crick FH. The origin of the genetic code. J Mol Biol. 1968;38: 367–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-2836(68)90392-6 | Karyorelict ciliates use an ambiguous genetic code with context-dependent stop/sense codons | Brandon Kwee Boon Seah, Aditi Singh, Estienne Carl Swart | <p style="text-align: justify;">In ambiguous stop/sense genetic codes, the stop codon(s) not only terminate translation but can also encode amino acids. Such codes have evolved at least four times in eukaryotes, twice among ciliates (<em>Condylost... |  | Bioinformatics, Evolutionary genomics | Iker Irisarri | 2022-05-02 11:06:10 | View |

FOLLOW US

MANAGING BOARD

Gavin Douglas

Jean-François Flot

Danny Ionescu