Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

22 Oct 2024

Chromosome level genome reference of the Caucasian dwarf goby Knipowitschia cf. caucasica, a new alien Gobiidae invading the River RhineAlexandra Schoenle, Nadège Guiglielmoni, Tobias Mainz, Carola Greve, Alexander B. Hamadou, Lisa Heermann, Jost Borcherding, Ann-Marie Waldvogel https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.04.22.590508New chromosome-scale genome assembly for the Dwarf Goby, a River Rhine invaderRecommended by Iker Irisarri based on reviews by Tereza Manousaki, Ruiqi Li and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Tereza Manousaki, Ruiqi Li and 1 anonymous reviewer

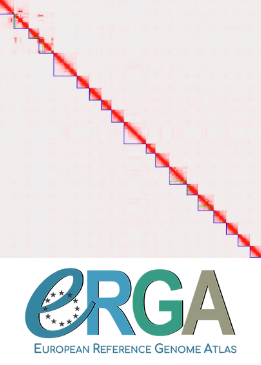

Since the opening of the Rhine-Main-Danube-Channel, four goby species are known to have invaded the River Rhine. Of these, the most recent and numerous is the Caucasian Dwarf Goby, which has been found in the Rhine since 2019. This study presents a new high-quality genome for this species (Knipowitschia cf. caucasica) (Schoenle et al. 2024). Currently, chromosome-scale genome assemblies represent a key first step in invasion biology, allowing the reconstruction of a species’ invasion history and monitoring its progress, as well as identifying and characterizing candidate genes that control invasiveness (McCartney et al. 2019). The authors sequenced the nuclear and mitochondrial genomes of this species using state-of-the art methods including long-read sequencing techniques, scaffolded based on chromatin conformation data, and annotated using both direct transcriptomic and protein homology evidence. Data analyses follow currently established pipelines for genome assembly, scaffolding, annotation, and downstream bioinformatic analyses. The quality of the final genome was thoroughly assessed and conforms to what is expected from other genomes of fishes in the family Gobiidae. This study follows other recent endeavors that generated high-quality genomes to improve our understanding of invasion biology (e.g. Shao et al. 2020 and Kitsoulis et al. 2023). These studies are successfully contributing to increasing the genomic resources for the world’s most damaging invasive species, which were not available for even a third of the top 100 invasive species just five years ago (McCarthy et al. 2019). Beyond invasion biology, the Dwarf Goby genome is also an important resource for many other applications, including evolutionary genomic analyses and phylogeography of this species and closely related ones in their native ranges. Kitsoulis CV, Papadogiannis V, Kristoffersen JB, Kaitetzidou E, Sterioti A, Tsigenopoulos CS, Manousaki T (2023) Near-chromosome level genome assembly of devil firefish, Pterois miles. Peer Community Journal 3:e64. https://doi.org/10.24072/pcjournal.295 McCartney MA, Mallez S, Gohl DM (2019) Genome projects in invasion biology. Conservation Genetics 20:1201–1222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10592-019-01224-x Schoenle A, Guiglielmoni N, Mainz T, Greve C, Hamadou AB, Heermann L, Borcherding J, Waldvogel A-M (2024) Chromosome level genome reference of the Caucasian dwarf goby Knipowitschia cf. caucasica, a new alien Gobiidae invading the River Rhine. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.04.22.590508 Shao F, Ludwig A, Mao Y, Liu N, Peng Z (2020). Chromosome-level genome assembly of the female western mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis). GigaScience 9:giaa092. https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giaa092

| Chromosome level genome reference of the Caucasian dwarf goby *Knipowitschia* cf. *caucasica*, a new alien Gobiidae invading the River Rhine | Alexandra Schoenle, Nadège Guiglielmoni, Tobias Mainz, Carola Greve, Alexander B. Hamadou, Lisa Heermann, Jost Borcherding, Ann-Marie Waldvogel | <p>The Caucasian dwarf goby <em>Knipowitschia</em> cf. <em>caucasica</em> is a new invasive alien Gobiidae spreading in the Lower Rhine since 2019. Little is known about the invasion biology of the species and further investigations to reconstruct... |  | ERGA, Vertebrates | Iker Irisarri | 2024-04-29 17:52:25 | View | |

19 Sep 2024

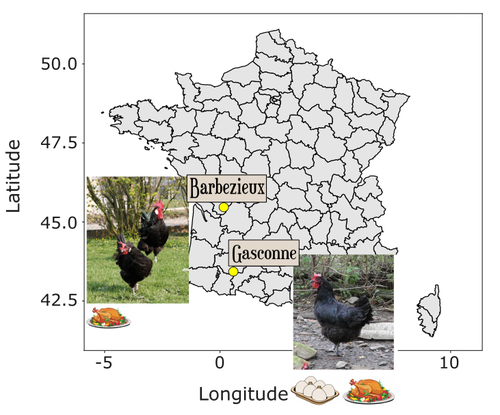

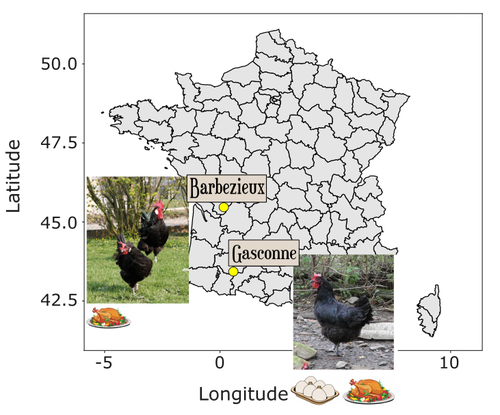

Trends in genome diversity of small populations under a conservation program: a case study of two French chicken breedsChiara Bortoluzzi, Gwendal Restoux, Romuald Rouger, Benoit Desnoues, Florence Petitjean, Mirte Bosse, Michele Tixier-Boichard https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.02.22.581528Professionalising conservation programmes for local chicken breedsRecommended by Claudia Kasper based on reviews by Markus Neuditschko and Claudia Fontsere Alemany based on reviews by Markus Neuditschko and Claudia Fontsere Alemany

While it is widely agreed that the conservation of local breeds is key to the maintenance of livestock biodiversity, the implementation of such programmes is often carried out by amateur breeders and may be inadequate due to a lack of knowledge and financial resources. Bortoluzzi et al. (2024) clearly demonstrate the utility of whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data for this purpose, compare two scenarios that differ in the consistency of conservation efforts, and provide valuable recommendations for conservation programmes. Genetic diversity in livestock is generally considered to be crucial to maintaining food security and ensuring the provision of necessary nutrients to humans (Godde et al. 2021). It is also important to recognise that the preservation of local breeds is a matter of cultural identity for certain regions, and that the products of these breeds are niche products which are in high demand. Especially today, as we face extreme weather conditions, drought and other consequences of global warming, modern breeds selected to perform under constant and temperate conditions are being challenged. The possibility of tapping into the reservoir of genetic variation held by traditional, locally adapted breeds offers an important option for breeding robust livestock. The best way to characterise genetic diversity is through modern molecular methods, based on whole genome sequencing and subsequent advanced population analyses, which has been demonstrated for domesticated and wild chicken (Qanbari et al. 2019). But are local breed conservation programmes up to the task? In their article, Bortoluzzi and colleagues show that well-designed and professionally managed conservation programmes for local chicken breeds are effective in maintaining genetic diversity. Their article is based on a comparison of two examples of conservation programmes for local chicken breeds: the Barbezieux and the Gasconne, which originated from comparably sized founder populations and for which WGS data were available in a biobank at two timepoints, 2003 and 2013, representing 10 generations. While the conservation programme for the former was continuous, that for the latter was interrupted and later started from scratch with a small number of sires and dams. The greater loss of genomic diversity in the Gasconne than in the Barbezieux shown in this article may therefore be unsurprising, but the authors provide a range of evidence for this using their population genomics toolbox. The less well-managed breed, Gasconne, shows a lower genome-wide heterozygosity, higher lengths of runs of homozygosity, higher levels of genomic inbreeding, a smaller effective population size and a higher genetic load in terms of predicted deleterious mutations. The sample sizes available for population genetic analyses are typically small for local breeds, which is difficult to change as the populations are very small at any given time. It is therefore all the more important to make the most out of it, and Bortoluzzi and co-authors approach the issue from several angles that help support their claim, using WGS data and the latest genomic resources. In addition to their analyses, the authors provide clear and valuable advice for the management of such conservation programmes. Their analysis of signatures of selection suggests that, apart from adult fertility, not much selection has been taking place. However, the authors emphasise that clear selection objectives other than maintaining the breed, such as production and product quality, can help conservation efforts by providing better guidelines for managing the programme and increasing the availability of resources for conservation programmes when the products of these local breeds become successful. In summary, Bortoluzzi et al. (2024) have provided a clear, well-written account of the impact of conservation programme management on the genetic diversity of local chicken breeds, using the most up-to-date genomic resources and analysis methods. As such, this article makes a significant and valuable contribution to the maintenance of genomic resources in livestock, providing approaches and lessons that will hopefully be adopted by other such initiatives. Bortoluzzi C, Restoux G, Rouger R, Desnoues B, Petitjean F, Bosse M, Tixier-Boichard M (2024) Trends in genome diversity of small populations under a conservation program: a case study of two French chicken breeds. bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.02.22.581528 Godde CM, Mason-D’Croz D, Mayberry DE, Thornton PK, Herrero M (2021) Impacts of climate change on the livestock food supply chain; a review of the evidence. Global Food Security 28:100488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2020.100488 Qanbari S, Rubin C-J, Maqbool K, Weigend S, Weigend A, Geibel J, Kerje S, Wurmser C, Peterson AT, IL Brisbin Jr., Preisinger R, Fries R, Simianer H, Andersson L (2019) Genetics of adaptation in modern chicken. PLOS Genetics, 15, e1007989. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1007989 | Trends in genome diversity of small populations under a conservation program: a case study of two French chicken breeds | Chiara Bortoluzzi, Gwendal Restoux, Romuald Rouger, Benoit Desnoues, Florence Petitjean, Mirte Bosse, Michele Tixier-Boichard | <p>Livestock biodiversity is declining globally at rates unprecedented in human history. Of all avian species, chickens are among the most affected ones because many local breeds have a small effective population size that makes them more suscepti... |  | Bioinformatics, Evolutionary genomics, Population genomics, Vertebrates | Claudia Kasper | 2024-02-26 13:01:08 | View | |

03 Sep 2024

A chromosome-level, haplotype-resolved genome assembly and annotation for the Eurasian minnow (Leuciscidae: Phoxinus phoxinus) provide evidence of haplotype diversityTemitope O. Oriowo, Ioannis Chrysostomakis, Sebastian Martin, Sandra Kukowka, Thomas Brown, Sylke Winkler, Eugene W. Myers, Astrid Boehne, Madlen Stange https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.30.569369Exploring evolutionary adaptations through Phoxinus phoxinus genomicsRecommended by Jitendra Narayan based on reviews by Alice Dennis and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Alice Dennis and 2 anonymous reviewers

Oriowo et al. (2024) offer a thorough and meticulously conducted study that makes a substantial contribution to our understanding of the Eurasian minnow (Phoxinus phoxinus), particularly in terms of its genetic diversity, structural variations, and evolutionary adaptations. The authors have achieved an impressive feat by generating an annotated haplotype-phased, chromosome-level genome assembly (2n = 50). This was accomplished through the integration of high-fidelity long reads with chromosome conformation capture data (Hi-C), resulting in a highly complete and accurate genome assembly. The assembly is characterized by a haploid size of 940 Megabase pairs (Mbp) for haplome one and 929 Mbp for haplome two, with scaffold N50 values of 36.4 Mb and 36.6 Mb, respectively. These metrics, alongside BUSCO scores of 96.9% and 97.2%, highlight the high quality of the genome, making it a robust foundation for further genetic exploration and analyses. The study’s findings are both novel and significant, providing deep insights into the genetic architecture of P. phoxinus. The authors report heterozygosity rate of 1.43% and a high repeat content of approximately 54%, primarily consisting of DNA transposons. These transposons play a crucial role in genome rearrangements and variations, contributing to the species' adaptability and evolution (Bourque et al. 2018). The research also identifies substantial structural variations within the genome, including insertions, deletions, inversions, and translocations (Oriowo et al. 2024). Beyond these findings, the genome annotation is exceptionally comprehensive, containing 30,980 mRNAs and 23,497 protein-coding genes. The study’s gene family evolution analysis, which compares the P. phoxinus proteome to that of ten other teleost species, reveals immune system gene families that favor histone-based disease prevention mechanisms over NLR-based immune responses. This provides new insight into the evolutionary strategies that have emerged in P. phoxinus, enabling its survival in its environment. Moreover, the demographic analysis conducted in the study reveals historical fluctuations in the effective population size of P. phoxinus, likely correlated with past climatic changes, offering insights into the species' evolutionary history. This annotated and phased reference genome not only serves as a crucial resource for resolving taxonomic complexities within the genus Phoxinus but also highlights the importance of haplotype-phased assemblies in understanding genetic diversity, particularly in species characterized by high heterozygosity. The authors have delivered a study that is methodologically sound, richly detailed, and highly relevant to the field. The study represents a valuable and impactful contribution to the scientific community, offering resources and knowledge that will likely inform future research in the field.

References Bourque G, Burns KH, Gehring M, Gorbunova V, Seluanov A, Hammell M, Imbeault M, Izsvák Z, Levin HL, Macfarlan TS, Mager DL, Feschotte C (2018) Ten things you should know about transposable elements. Genome Biology, 19, 199. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-018-1577-z Oriowo TO, Chrysostomakis I, Martin S, Kukowka S, Brown T, Winkler S, Myers EW, Böhne A, Stange M (2024) A chromosome-level, haplotype-resolved genome assembly and annotation for the Eurasian minnow (Leuciscidae: Phoxinus phoxinus) provide evidence of haplotype diversity. bioRxiv, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Genomics https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.30.569369 | A chromosome-level, haplotype-resolved genome assembly and annotation for the Eurasian minnow (Leuciscidae: *Phoxinus phoxinus*) provide evidence of haplotype diversity | Temitope O. Oriowo, Ioannis Chrysostomakis, Sebastian Martin, Sandra Kukowka, Thomas Brown, Sylke Winkler, Eugene W. Myers, Astrid Boehne, Madlen Stange | <p>In this study we present an in-depth analysis of the Eurasian minnow (<em>Phoxinus phoxinus</em>) genome, highlighting its genetic diversity, structural variations, and evolutionary adaptations. We generated an annotated haplotype-phased, chrom... |  | Evolutionary genomics, Structural genomics, Vertebrates | Jitendra Narayan | Henrik Lanz, Rui Borges, Fergal Martin, Vinod Scaria, Mihai Pop, Alice Dennis, Jin-Wu Nam, Monya Baker, Giuseppe Narzisi | 2023-12-04 14:49:17 | View |

21 Aug 2024

MATEdb2, a collection of high-quality metazoan proteomes across the Animal Tree of Life to speed up phylogenomic studiesGemma I. Martínez-Redondo, Carlos Vargas-Chávez, Klara Eleftheriadi, Lisandra Benítez-Álvarez, Marçal Vázquez-Valls, Rosa Fernández https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.02.21.581367MATEdb2 is a valuable phylogenomics resource across MetazoaRecommended by Philipp Schiffer based on reviews by Natasha Glover and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Natasha Glover and 1 anonymous reviewer

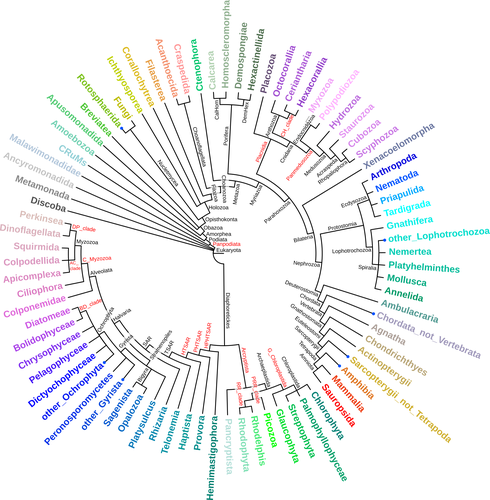

Martínez-Redondo and colleagues (2024) present MATEdb2, which provides the scientific community with Metazoa proteomes that have been predicted and annotated in a standardised way. The authors improved the taxon representation from the earlier MATEdb and their current database has a strong focus on Arthropoda, Annelida, and Mollusca. In particular, for the latter two groups not many high-quality reference genomes are available. Standardisation of the prediction and annotation process in a reproducible pipeline, as integrated in MATEdb2, is of great value, in particular to infer phylogenies as correctly as possible. Thus, I am sure that MATEdb2 will be an excellent go-to resource for phylogenomic studies, as well as for probing the biology of new, obscure species, especially marine ones.

| MATEdb2, a collection of high-quality metazoan proteomes across the Animal Tree of Life to speed up phylogenomic studies | Gemma I. Martínez-Redondo, Carlos Vargas-Chávez, Klara Eleftheriadi, Lisandra Benítez-Álvarez, Marçal Vázquez-Valls, Rosa Fernández | <p>Recent advances in high throughput sequencing have exponentially increased the number of genomic data available for animals (Metazoa) in the last decades, with high-quality chromosome-level genomes being published almost daily. Nevertheless, ge... |  | Arthropods, Bioinformatics, Evolutionary genomics, Marine invertebrates, Terrestrial invertebrates | Philipp Schiffer | 2024-03-04 11:37:21 | View | |

12 Aug 2024

A Comprehensive Resource for Exploring Antiphage Defense: DefenseFinder Webservice, Wiki and DatabasesF. Tesson, R. Planel, A. Egorov, H. Georjon, H. Vaysset, B. Brancotte, B. Néron, E. Mordret, A Bernheim, G. Atkinson, J. Cury https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.01.25.577194DefenseFinder update advances prokaryotic antiviral system researchRecommended by Sishuo Wang based on reviews by Pierre Pontarotti , Pedro Leão and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Pierre Pontarotti , Pedro Leão and 1 anonymous reviewer

Prokaryotic antiviral systems, such as CRISPR-Cas and restriction-modification systems, provide defense against viruses through diverse mechanisms including intracellular signaling, chemical defense, and nucleotide depletion. However, bioinformatic tools and resources for identifying and cataloging these systems are still in development. The work by Tesson and colleagues (2024) presents a significant advancement in understanding the defense systems of prokaryotes. The authors have provided an update of their previously developed online service DefenseFinder, which helps to detect known antiviral systems in prokaryotes genomes (Tesson et al. 2022), plus three new databases: one serving as a wiki for defense systems, one housing experimentally determined and AlphaFold2-predicted structures, and a third one consisting of precomputed results from DefenseFinder. Users can analyze their own data through the user-friendly interface. This initiative will help promote a community-driven approach to sharing knowledge on antiphage systems, which is very useful given their complexity and diversity. The authors' commitment to maintaining an up-to-date platform and encouraging community contributions makes this resource accessible to both newcomers and experienced researchers in the rapidly growing field of defense system research. Experienced researchers will find that there are ways to contribute to the future expansion of these databases, while new users can easily access and use the platform. Overall, the updated DefenseFinder, as well as the other databases introduced in the manuscript, are well-suited for researchers (both dry- and wet-lab ones) interested in antiphage defense. I am hopeful that the efforts by the authors will collectively create valuable online resources for researchers in this field and will foster an environment of open science and accessible bioinformatics tools.

References Tesson F, Hervé A, Mordret E, Touchon M, d’Humières C, Cury J, Bernheim A (2022) Systematic and quantitative view of the antiviral arsenal of prokaryotes. Nature Communications, 13, 2561. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-30269-9 Tesson F, Planel R, Egorov A, Georjon H, Vaysset H, Brancotte B, Néron B, Mordret E, Atkinson G, Bernheim A, Cury J (2024) A comprehensive resource for exploring antiphage defense: DefenseFinder webservice, wiki and databases. bioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.01.25.577194 | A Comprehensive Resource for Exploring Antiphage Defense: DefenseFinder Webservice, Wiki and Databases | F. Tesson, R. Planel, A. Egorov, H. Georjon, H. Vaysset, B. Brancotte, B. Néron, E. Mordret, A Bernheim, G. Atkinson, J. Cury | <p>In recent years, a vast number of novel antiphage defense mechanisms were uncovered. To<br>facilitate the exploration of mechanistic, ecological, and evolutionary aspects related to antiphage defense systems, we released DefenseFinder in 2021 (... |  | Bacteria and archaea, Bioinformatics, Evolutionary genomics, Viruses and transposable elements | Sishuo Wang | 2024-04-17 18:30:32 | View | |

06 Aug 2024

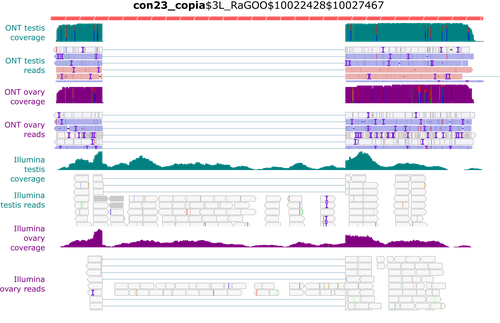

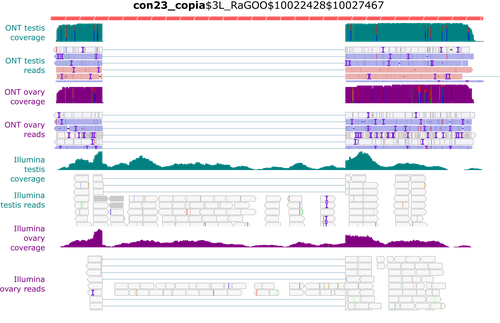

Identification and quantification of transposable element transcripts using Long-Read RNA-seq in Drosophila germline tissuesRita Rebollo, Pierre Gerenton, Eric Cumunel, Arnaud Mary, François Sabot, Nelly Burlet, Benjamin Gillet, Sandrine Hughes, Daniel Siqueira Oliveira, Clément Goubert, Marie Fablet, Cristina Vieira, Vincent Lacroix https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.27.542554Unveiling transposon dynamics: Advancing TE expression analysis in Drosophila with long-read sequencingRecommended by Nicolas Pollet based on reviews by Silke Jensen, Christophe Antoniewski and 1 anonymous reviewerTransposable elements (TEs) are mobile genetic elements with an intrinsic mutagenic potential that influences the physiology of any cell type, whether somatic or germinal. Measuring TE expression is a fundamental prerequisite for analysing the processes leading to the activity of TE-derived sequences. This applies to both old and recent TEs, as even if they are deficient in mobilisation, transcription of TE sequences alone can impact neighbouring gene expression and other cellular activities. In terms of TE physiology, transcription is crucial for mobilisation activity. The transcription of some TEs can be tissue-specific and associated with splicing events, as exemplified by the P-element isoforms in the fruit fly (Laski et al. 1986). Regarding host cell physiology, TE transcripts can include nearby exons, with or without splicing, and such chimeric transcripts can significantly alter gene activity. Thus, quantitative and qualitative analyses must be conducted to assess TE function and how they can modify genomic activities. Yet, due to the polymorphic, interspersed, and repetitive nature of TE sequences, the quantitative and qualitative analysis of TE transcript levels using short-read sequencing remains challenging (Lanciano and Cristofari 2020). In this context, Rebollo et al. (2024) employed nanopore long-read sequencing to analyse cDNAs derived from Drosophila melanogaster germline RNAs. The authors constructed two long-read cDNA libraries from pooled ovaries and testes using a protocol to obtain full-length cDNAs and sequenced them separately. They carefully compared their results with their short-read datasets. Overall, their observations corroborate known patterns of germline-specific expression of certain TEs and provide initial evidence of novel spliced TE transcript isoforms in Drosophila. Rebollo and colleagues have provided a well-documented and detailed analysis of their results, which will undoubtedly benefit the scientific community. They presented the challenges and limitations of their approach, such as the length of the transcripts, and provided a reproducible analysis workflow that will enable better characterisation of TE expression using long-read technology. Despite the small number of samples and limited sequencing depth, this pioneering study strikingly demonstrates the potential of long-read sequencing for the quantitative and qualitative analysis of TE transcription, a technology that will facilitate a better understanding of the transposon landscape. Lanciano S, Cristofari G (2020) Measuring and interpreting transposable element expression. Nature Reviews Genetics, 21, 721–736. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-020-0251-y Laski FA, Rio DC, Rubin GM (1986) Tissue specificity of Drosophila P element transposition is regulated at the level of mRNA splicing. Cell, 44, 7–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(86)90480-0 Rebollo R, Gerenton P, Cumunel E, Mary A, Sabot F, Burlet N, Gillet B, Hughes S, Oliveira DS, Goubert C, Fablet M, Vieira C, Lacroix V (2024) Identification and quantification of transposable element transcripts using Long-Read RNA-seq in Drosophila germline tissues. bioRxiv, ver.4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.27.542554 | Identification and quantification of transposable element transcripts using Long-Read RNA-seq in Drosophila germline tissues | Rita Rebollo, Pierre Gerenton, Eric Cumunel, Arnaud Mary, François Sabot, Nelly Burlet, Benjamin Gillet, Sandrine Hughes, Daniel Siqueira Oliveira, Clément Goubert, Marie Fablet, Cristina Vieira, Vincent Lacroix | <p>Transposable elements (TEs) are repeated DNA sequences potentially able to move throughout the genome. In addition to their inherent mutagenic effects, TEs can disrupt nearby genes by donating their intrinsic regulatory sequences, for instance,... |  | Arthropods, Bioinformatics, Viruses and transposable elements | Nicolas Pollet | 2023-06-13 14:46:20 | View | |

05 Aug 2024

LukProt: A database of eukaryotic predicted proteins designed for investigations of animal originsŁukasz F. Sobala https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.01.30.577650A protein database to study the origin of metazoansRecommended by Javier del Campo based on reviews by Giacomo Mutti and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Giacomo Mutti and 2 anonymous reviewers

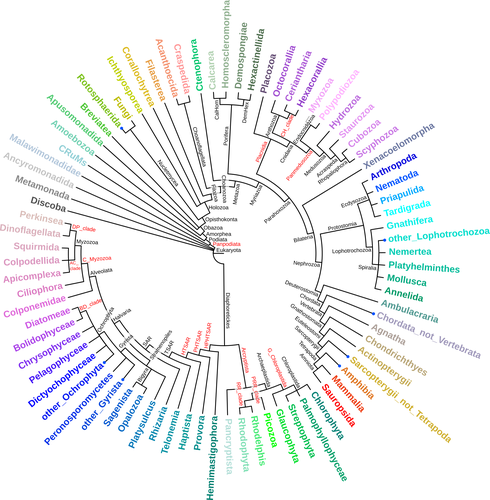

Sobala (2024) introduces a new, comprehensive, and curated eukaryotic database. It consolidates information from EukProt (Richter et al. 2022) and various other resources to enhance Metazoa representation in existing protein databases. The preprint is of significant interest to the phylogenomics and comparative genomics communities, and I commend the author for their work. LukProt, the expanded database, significantly increases the taxon sampling within holozoans. It integrates data from the previously assembled EukProt and AniProtDB (Barreira et al. 2021) databases, with additional datasets from early-diverging animal lineages such as ctenophores, sponges, and cnidarians. This effort will undoubtedly be useful for researchers investigating these clades and their origins, as well as for the broader field of comparative genomics. The author provides both web-portal and command-line versions of the database, making it accessible to users with varying degrees of bioinformatic proficiency. The curation effort is commendable, and I believe the comparative genomics community, especially those interested in animal origins, will find LukProt to be a valuable resource.

References Barreira SN, Nguyen A-D, Fredriksen MT, Wolfsberg TG, Moreland RT, Baxevanis AD (2021) AniProtDB: A collection of consistently generated metazoan proteomes for comparative genomics studies. Molecular Biology and Evolution 38, 4628–4633. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msab165 Richter DJ, Berney C, Strassert JFH, Poh Y-P, Herman EK, Muñoz-Gómez SA, Wideman JG, Burki F, de Vargas C (2022) EukProt: A database of genome-scale predicted proteins across the diversity of eukaryotes. Peer Community Journal 2, e56. https://doi.org/10.24072/pcjournal.173 Sobala ŁF (2024) LukProt: A database of eukaryotic predicted proteins designed for investigations of animal origins. bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.01.30.577650 | LukProt: A database of eukaryotic predicted proteins designed for investigations of animal origins | Łukasz F. Sobala | <p>The origins and early evolution of animals is a subject with many outstanding questions. One problem faced by researchers trying to answer them is the absence of a comprehensive database of sequences from non-bilaterians. Publicly available dat... |  | Bioinformatics, Evolutionary genomics, Marine invertebrates | Javier del Campo | Anonymous, Giacomo Mutti , Anonymous | 2024-02-02 13:04:31 | View |

13 Jul 2024

High quality genome assembly and annotation (v1) of the eukaryotic terrestrial microalga Coccomyxa viridis SAG 216-4Anton Kraege, Edgar Chavarro-Carrero, Nadège Guiglielmoni, Eva Schnell, Joseph Kirangwa, Stefanie Heilmann-Heimbach, Kerstin Becker, Karl Köhrer, Philipp Schiffer, Bart P. H. J. Thomma, Hanna Rovenich https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.11.548521Reference genome for the lichen-forming green alga Coccomyxa viridis SAG 216–4Recommended by Iker Irisarri based on reviews by Elisa Goldbecker, Fabian Haas and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Elisa Goldbecker, Fabian Haas and 2 anonymous reviewers

Green algae of the genus Coccomyxa (family Trebouxiophyceae) are extremely diverse in their morphology, habitat (i.e., in marine, freshwater, and terrestrial environments) and lifestyle, including free-living and mutualistic forms. Coccomyxa viridis (strain SAG 216–4) is a photobiont in the lichen Peltigera aphthosa, which was isolated in Switzerland more than 70 years ago (cf. SAG, the Culture Collection of Algae at the University of Göttingen, Germany). Despite the high diversity and plasticity in Coccomyxa, integrative taxonomic analyses led Darienko et al. (2015) to propose clear species boundaries. These authors also showed that symbiotic strains that form lichens evolved multiple times independently in Coccomyxa. Using state-of-the-art sequencing data and bioinformatic methods, including Pac-Bio HiFi and ONT long reads, as well as Hi-C chromatin conformation information, Kraege et al. (2024) generated a high-quality genome assembly for the Coccomyxa viridis strain SAG 216–4. They reconstructed 19 complete nuclear chromosomes, flanked by telomeric regions, totaling 50.9 Mb, plus the plastid and mitochondrial genomes. The performed quality controls leave no doubt of the high quality of the genome assemblies and structural annotations. An interesting observation is the lack of conserved synteny with the close relative Coccomyxa subellipsoidea, but further comparative studies with additional Coccomyxa strains will be required to grasp the genomic evolution in this genus of green algae. This project is framed within the ERGA pilot project, which aims to establish a pan-European genomics infrastructure and contribute to cataloging genomic biodiversity and producing resources that can inform conservation strategies (Formenti et al. 2022). This complete reference genome represents an important step towards this goal, in addition to contributing to future genomic analyses of Coccomyxa more generally.

References Darienko T, Gustavs L, Eggert A, Wolf W, Pröschold T (2015) Evaluating the species boundaries of green microalgae (Coccomyxa, Trebouxiophyceae, Chlorophyta) using integrative taxonomy and DNA barcoding with further implications for the species identification in environmental samples. PLOS ONE, 10, e0127838. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127838 Formenti G, Theissinger K, Fernandes C, Bista I, Bombarely A, Bleidorn C, Ciofi C, Crottini A, Godoy JA, Höglund J, Malukiewicz J, Mouton A, Oomen RA, Paez S, Palsbøll PJ, Pampoulie C, Ruiz-López MJ, Svardal H, Theofanopoulou C, de Vries J, Waldvogel A-M, Zhang G, Mazzoni CJ, Jarvis ED, Bálint M, European Reference Genome Atlas Consortium (2022) The era of reference genomes in conservation genomics. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 37, 197–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2021.11.008 Kraege A, Chavarro-Carrero EA, Guiglielmoni N, Schnell E, Kirangwa J, Heilmann-Heimbach S, Becker K, Köhrer K, WGGC Team, DeRGA Community, Schiffer P, Thomma BPHJ, Rovenich H (2024) High quality genome assembly and annotation (v1) of the eukaryotic terrestrial microalga Coccomyxa viridis SAG 216-4. bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.11.548521 | High quality genome assembly and annotation (v1) of the eukaryotic terrestrial microalga *Coccomyxa viridis* SAG 216-4 | Anton Kraege, Edgar Chavarro-Carrero, Nadège Guiglielmoni, Eva Schnell, Joseph Kirangwa, Stefanie Heilmann-Heimbach, Kerstin Becker, Karl Köhrer, Philipp Schiffer, Bart P. H. J. Thomma, Hanna Rovenich | <p>Unicellular green algae of the genus Coccomyxa are recognized for their worldwide distribution and ecological versatility. Most species described to date live in close association with various host species, such as in lichen associations. Howev... |  | ERGA Pilot | Iker Irisarri | 2023-11-09 11:54:43 | View | |

03 Jul 2024

T7 DNA polymerase treatment improves quantitative sequencing of both double-stranded and single-stranded DNA virusesMaud Billaud, Ilias Theodorou, Quentin Lamy-Besnier, Shiraz Shah, François Lecointe, Luisa De Sordi, Marianne De Paepe, Marie-Agnès Petit https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.12.520144Improving the sequencing of single-stranded DNA viruses: Another brick for building Earth's complete virome encyclopediaRecommended by Sebastien Massart based on reviews by Philippe Roumagnac and 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Philippe Roumagnac and 3 anonymous reviewers

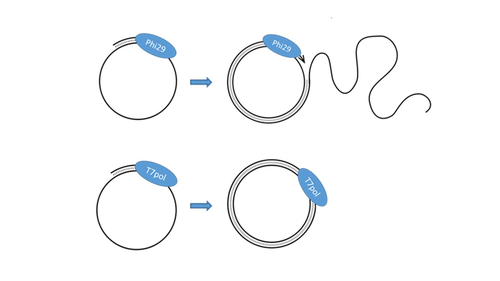

The wide adoption of high-throughput sequencing technologies has uncovered an astonishing diversity of viruses in most biosphere habitats. Among them, single-stranded DNA viruses are prevalent, infecting diverse hosts from all three domains of life (Malathi et al. 2014) with some species being highly pathogenic to animals or plants. Sequencing of single-stranded DNA viruses requires a specific approach that usually leads to their over-representation compared to double-stranded DNA. The article from Billaud et al. (2024) addresses this challenge. It presents a novel and efficient method for converting single-stranded DNA to double-stranded DNA using T7 DNA polymerase before high-throughput virome sequencing. It compares this new method with the Phi29 polymerase method, demonstrating its advantages in the representation and accuracy of viral DNA content in well-defined synthetic phage mixtures and complex human virome samples from the stool. This T7 DNA polymerase treatment significantly improved the richness and abundance of the Microviridae fraction in their samples, suggesting a more comprehensive representation of viral diversity. The article presents a compelling case for testing and adopting the T7 DNA polymerase methodology in preparing virome samples for shotgun sequencing. This novel approach, supported by comparative analysis with existing methodologies, represents a valuable contribution to metagenomics for characterizing virome diversity.

References Billaud M, Theodorou I, Lamy-Besnier Q, Shah SA, Lecointe F, Sordi LD, Paepe MD, Petit M-A (2024) T7 DNA polymerase treatment improves quantitative sequencing of both double-stranded and single-stranded DNA viruses. bioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.12.520144 Malathi VG, Renuka Devi P. (2019) ssDNA viruses: key players in global virome. Virus disease. 30: 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13337-019-00519-4

| T7 DNA polymerase treatment improves quantitative sequencing of both double-stranded and single-stranded DNA viruses | Maud Billaud, Ilias Theodorou, Quentin Lamy-Besnier, Shiraz Shah, François Lecointe, Luisa De Sordi, Marianne De Paepe, Marie-Agnès Petit | <p>Background: Bulk microbiome, as well as virome-enriched shotgun sequencing only reveals the double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) content of a given sample, unless specific treatments are applied. However, genomes of viruses often consist of a circular s... |  | Viruses and transposable elements | Sebastien Massart | 2023-12-20 16:50:00 | View | |

01 Jul 2024

Contextualising samples: Supporting reference genomes of European biodiversity through sample and associated metadata collectionAstrid Böhne, Rosa Fernández, Jennifer A. Leonard, Ann M. McCartney, Seanna McTaggart, José Melo-Ferreira, Rita Monteiro, Rebekah A. Oomen, Olga Vinnere Pettersson, Torsten H. Struck https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.28.546652To avoid biases and to be FAIR, we need to CARE and share biodiversity metadataRecommended by Francois Sabot based on reviews by Julian Osuji and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Julian Osuji and 1 anonymous reviewer

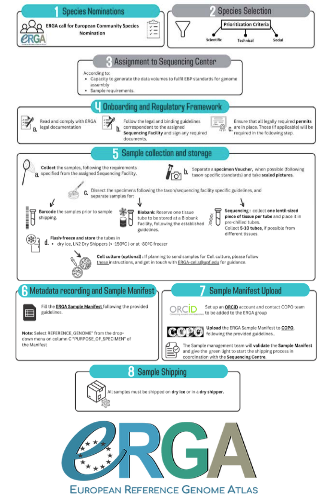

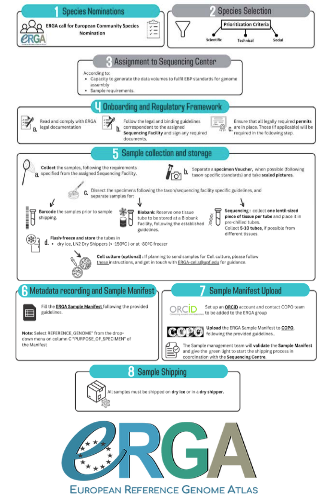

Böhne et al. (2024) do not present a classical scientific paper per se but a report on how the European Reference Genome Atlas (ERGA) aims to deal with sampling and sample information, i.e. metadata. As the goal of ERGA is to provide an almost fully representative set of reference genomes representative of European biodiversity to serve many research areas in biology, they have to be really exhaustive. In this regard, in addition to providing sample metadata recording guidelines, they also discuss the biases existing in sampling and sequencing projects. The first task for such a project is to be sure that the data they generate will be usable and available in the future (“[in] perpetuity", Böhne et al. 2024). The authors deployed a very efficient pipeline for conserving information on sampling: location, physical information, copies of tissues and of DNA, shipping, legal/ethical aspects regarding the Nagoya Protocol, etc., alongside a best-practice manual. This effort is linked to practical guides for the DNA extraction of specific taxa. More generally, these details enable “Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable” (FAIR) principles (Wilkinson et al. 2016) to be followed. An important aspect of this paper, in addition to practical points, is the reflection upon the different biases inherent to the choice of sequenced samples. Acknowledging their own biases with regards to DNA extraction protocol efficiency, small genome size choice, as well as the availability of material (Nagoya Protocol aspects) and material transfer efficiency, the authors recommend in the future to not survey biodiversity by selecting one’s favorite samples or species, but also considering "orphan" taxa. Some of these "orphan" taxonomic groups belong to non-arthropod invertebrates but internal disparities are also prominent within other taxa. Finally, the implementation of the "Collective benefit, Authority to control, Responsibility, and Ethics" (CARE) principles (Carroll et al. 2021) will allow Indigenous rights to be considered when prioritizing samples, and to enable their "knowledge systems to permeate throughout the process of reference genome production and beyond" (Böhne et al. 2024). Last, but not least, as ERGA, including its Sampling and Sample Processing committee, is a large collective effort, it is very refreshing to read a paper starting with the acknowledgements and the roles of each member.

References Böhne A, Fernández R, Leonard JA, McCartney AM, McTaggart S, Melo-Ferreira J, Monteiro R, Oomen RA, Pettersson OV, Struck TH (2024) Contextualising samples: Supporting reference genomes of European biodiversity through sample and associated metadata collection. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.28.546652 Carroll SR, Herczog E, Hudson M, Russell K, Stall S (2021) Operationalizing the CARE and FAIR Principles for Indigenous data futures. Scientific Data, 8, 108. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-021-00892-0 Wilkinson MD, Dumontier M, Aalbersberg IjJ, Appleton G, Axton M, Baak A, Blomberg N, Boiten J-W, da Silva Santos LB, Bourne PE, Bouwman J, Brookes AJ, Clark T, Crosas M, Dillo I, Dumon O, Edmunds S, Evelo CT, Finkers R, Gonzalez-Beltran A, Gray AJG, Groth P, Goble C, Grethe JS, Heringa J, ’t Hoen PAC, Hooft R, Kuhn T, Kok R, Kok J, Lusher SJ, Martone ME, Mons A, Packer AL, Persson B, Rocca-Serra P, Roos M, van Schaik R, Sansone S-A, Schultes E, Sengstag T, Slater T, Strawn G, Swertz MA, Thompson M, van der Lei J, van Mulligen E, Velterop J, Waagmeester A, Wittenburg P, Wolstencroft K, Zhao J, Mons B (2016) The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data, 3, 160018. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18 | Contextualising samples: Supporting reference genomes of European biodiversity through sample and associated metadata collection | Astrid Böhne, Rosa Fernández, Jennifer A. Leonard, Ann M. McCartney, Seanna McTaggart, José Melo-Ferreira, Rita Monteiro, Rebekah A. Oomen, Olga Vinnere Pettersson, Torsten H. Struck | <p>The European Reference Genome Atlas (ERGA) consortium aims to generate a reference genome catalogue for all of Europe's eukaryotic biodiversity. The biological material underlying this mission, the specimens and their derived samples, are provi... |  | ERGA, ERGA BGE, ERGA Pilot, Evolutionary genomics | Francois Sabot | Julian Osuji, Francois Sabot, Anonymous | 2023-07-03 10:39:36 | View |

FOLLOW US

MANAGING BOARD

Gavin Douglas

Jean-François Flot

Danny Ionescu