DOUGLAS Gavin

- Biological Sciences, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, United States

- Bacteria and archaea, Bioinformatics, Evolutionary genomics, Metagenomics, Population genomics

- recommender, administrator, manager

Recommendations: 4

Review: 1

Recommendations: 4

Evolution of ion channels in cetaceans: A natural experiment in the tree of life

Positive selection acted upon cetacean ion channels during the aquatic transition

Recommended by Gavin Douglas based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThe transition of cetaceans (whales, dolphins, and porpoises) from terrestrial to aquatic lifestyles is a striking example of natural selection driving major phenotypic changes (Figure 1). For instance, cetaceans have evolved the ability to withstand high pressure and to store oxygen for long periods, among other adaptations (Das et al. 2023). Many phenotypic changes, such as shifts in organ structure, have been well-characterized through fossils (Thewissen et al. 2009). Although such phenotypic transitions are now well understood, we have only a partial understanding of the underlying genetic mechanisms. Scanning for signatures of adaptation in genes related to phenotypes of interest is one approach to better understand these mechanisms. This was the focus of Uribe and colleagues’ (2024) work, who tested for such signatures across cetacean protein-coding genes.

Figure 1: The skeletons of Ambulocetus (an early whale; top) and Pakicetus (the earliest known cetacean, which lived about 50 million years ago; bottom). Copyright: J. G. M. Thewissen. Displayed here with permission from the copyright holder.

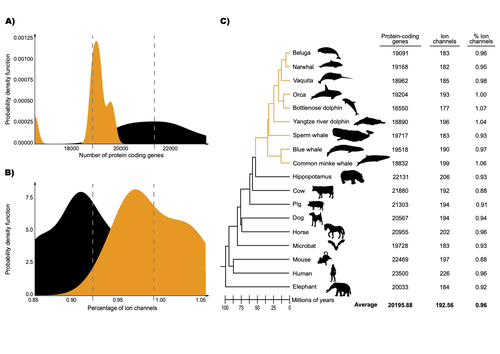

The authors were specifically interested in investigating the evolution of ion channels, as these proteins play fundamental roles in physiological processes. An important aspect of their work was to develop a bioinformatic pipeline to identify orthologous ion channel genes across a set of genomes. After applying their bioinformatic workflow to 18 mammalian species (including nine cetaceans), they conducted tests to find out whether these genes showed signatures of positive selection in the cetacean lineage. For many ion channel genes, elevated ratios of non-synonymous to synonymous substitution rates were detected (for at least a subset of sites, and not necessarily the entire coding region of the genes). The genes concerned were enriched for several functions, including heart and nervous system-related phenotypes.

One top gene hit among the putatively selected genes was SCN5A, which encodes a sodium channel expressed in the heart. Interestingly, the authors noted a specific amino acid replacement, which is associated with sensitivity to the toxin tetrodotoxin in other lineages. This substitution appears to have occurred in the common ancestor of toothed whales, and then was reversed in the ancestor of bottlenose dolphins. The authors describe known bottlenose dolphin interactions with toxin-producing pufferfish that could result in high tetrodotoxin exposure, and thus perhaps higher selection for tetrodotoxin resistance. Although this observation is intriguing, the authors emphasize it requires experimental confirmation.

The authors also recapitulated the previously described observation (Yim et al. 2014; Huelsmann et al. 2019) that cetaceans have fewer protein-coding genes compared to terrestrial mammals, on average. This signal has previously been hypothesized to partially reflect adaptive gene loss. For example, specific gene loss events likely decreased the risk of developing blood clots while diving (Huelsmann et al. 2019). Uribe and colleagues also considered overall gene turnover rate, which encompasses gene copy number variation across lineages, and found the cetacean gene turnover rate to be three times higher than that of terrestrial mammals. Finally, they found that cetaceans have a higher proportion of ion channel genes (relative to all protein-coding genes in a genome) compared to terrestrial mammals.

Similar investigations of the relative non-synonymous to synonymous substitution rates across cetacean and terrestrial mammal orthologs have been conducted previously, but these have primarily focused on dolphins as the sole cetacean representative (McGowen et al. 2012; Nery et al. 2013; Sun et al. 2013). These projects have also been conducted across a large proportion of orthologous genes, rather than a subset with a particular function. Performing proteome-wide investigations can be valuable in that they summarize the genome-wide signal, but can suffer from a high multiple testing burden. More generally, investigating a more targeted question, such as the extent of positive selection acting on ion channels in this case, or on genes potentially linked to cetaceans’ increased brain sizes (McGowen et al. 2011) or hypoxia tolerance (Tian et al. 2016), can be easier to interpret, as opposed to summarizing broader signals. However, these smaller-scale studies can also experience a high multiple testing burden, especially as similar tests are conducted across numerous studies, which often is not accounted for (Ioannidis 2005). In addition, integrating signals across the entire genome will ultimately be needed given that many genetic changes undoubtedly underlie cetaceans’ phenotypic diversification. As highlighted by the fact that past genome-wide analyses have produced some differing biological interpretations (McGowen et al. 2012; Nery et al. 2013; Sun et al. 2013), this is not a trivial undertaking.

Nonetheless, the work performed in this preprint, and in related research, is valuable for (at least) three reasons. First, although it is a challenging task, a better understanding of the genetic basis of cetacean phenotypes could have benefits for many aspects of cetacean biology, including conservation efforts. In addition, the remarkable phenotypic shifts in cetaceans make the question of what genetic mechanisms underlie these changes intrinsically interesting to a wide audience. Last, since the cetacean fossil record is especially well-documented (Thewissen et al. 2009), cetaceans represent an appealing system to validate and further develop statistical methods for inferring adaptation from genetic data. Uribe and colleagues’ (2024) analyses provide useful insights relevant to each of these points, and have generated intriguing hypotheses for further investigation.

References

Das K, Sköld H, Lorenz A, Parmentier E (2023) Who are the marine mammals? In: “Marine Mammals: A Deep Dive into the World of Science”. Brennecke D, Knickmeier K, Pawliczka I, Siebert U, Wahlberg, M (editors). Springer, Cham. p. 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-06836-2_1

Huelsmann M, Hecker N, Springer MS, Gatesy J, Sharma V, Hiller M (2019) Genes lost during the transition from land to water in cetaceans highlight genomic changes associated with aquatic adaptations. Science Advances, 5, eaaw6671. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aaw6671

Ioannidis JPA (2005) Why most published research findings are false. PLOS Medicine, 2, e124. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124

McGowen MR, Montgomery SH, Clark C, Gatesy J (2011) Phylogeny and adaptive evolution of the brain-development gene microcephalin (MCPH1) in cetaceans. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 11, 98. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-11-98

McGowen MR, Grossman LI, Wildman DE (2012) Dolphin genome provides evidence for adaptive evolution of nervous system genes and a molecular rate slowdown. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 279, 3643–3651. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.0869

Nery MF, González DJ, Opazo JC (2013) How to make a dolphin: molecular signature of positive selection in cetacean genome. PLOS ONE, 8, e65491. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0065491

Sun YB, Zhou WP, Liu HQ, Irwin DM, Shen YY, Zhang YP (2013) Genome-wide scans for candidate genes involved in the aquatic adaptation of dolphins. Genome Biology and Evolution, 5, 130–139. https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evs123

Tian R, Wang Z, Niu X, Zhou K, Xu S, Yang G (2016) Evolutionary genetics of hypoxia tolerance in cetaceans during diving. Genome Biology and Evolution, 8, 827–839. https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evw037

Thewissen JGM, Cooper LN, George JC, Bajpai (2009) From land to water: the origin of whales, dolphins, and porpoises. Evolution: Education and Outreach, 2, 272–288. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12052-009-0135-2

Uribe C, Nery M, Zavala K, Mardones G, Riadi G, Opazo J (2024) Evolution of ion channels in cetaceans: A natural experiment in the tree of life. bioRxiv, ver. 8 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.15.545160

Yim HS, Cho YS, Guang X, Kang SG, Jeong JY, Cha SS, Oh HM, Lee JH, Yang EC, Kwon KK, et al. (2014) Minke whale genome and aquatic adaptation in cetaceans. Nature Genetics, 46, 88–92. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2835

MacSyFinder v2: Improved modelling and search engine to identify molecular systems in genomes

A unique and customizable approach for functionally annotating prokaryotic genomes

Recommended by Gavin Douglas based on reviews by Kwee Boon Brandon Seah and Max Emil SchönMacromolecular System Finder (MacSyFinder) v2 (Néron et al., 2023) is a newly updated approach for performing functional annotation of prokaryotic genomes (Abby et al., 2014). This tool parses an input file of protein sequences from a single genome (either ordered by genome location or unordered) and identifies the presence of specific cellular functions (referred to as “systems”). These systems are called based on two criteria: (1) that the "quorum" of a minimum set of core proteins involved is reached the “quorum” of a minimum set of core proteins being involved that are present, and (2) that the genes encoding these proteins are in the expected genomic organization (e.g., within the same order in an operon), when ordered data is provided. I believe the MacSyFinder approach represents an improvement over more commonly used methods exactly because it can incorporate such information on genomic organization, and also because it is more customizable.

Before properly appreciating these points, it is worth noting the norms and key challenges surrounding high-throughput functional annotation of prokaryotic genomes. Genome sequences are being added to online repositories at increasing rates, which has led to an enormous amount of bacterial genome diversity available to investigate (Altermann et al., 2022). A key aspect of understanding this diversity is the functional annotation step, which enables genes to be grouped into more biologically interpretable categories. For instance, gene calls can be mapped against existing Clusters of Orthologous Genes, which are themselves grouped into general categories such as ‘Transcription’ and ‘Lipid metabolism’ (Galperin et al., 2021).

This approach is valuable but is primarily used for global summaries of functional annotations within a genome: for example, it could be useful to know that a genome is particularly enriched for genes involved in lipid metabolism. However, knowing that a particular gene is involved in the general process of lipid metabolism is less likely to be actionable. In other words, the desired specificity of a gene’s functional annotation will depend on the exact question being investigated. There is no shortage of functional ontologies in genomics that can be applied for this purpose (Douglas and Langille, 2021), and researchers are often overwhelmed by the choice of which functional ontology to use. In this context, giving researchers the ability to precisely specify the gene families and operon structures they are interested in identifying across genomes provides useful control over what precise functions they are profiling. Of course, most researchers will lack the information and/or expertise to fully take advantage of MacSyFinder’s customizable features, but having this option for specialized purposes is valuable.

The other MacSyFinder feature that I find especially noteworthy is that it can incorporate genomic organization (e.g., of genes ordered in operons) when calling systems. This is a rare feature among commonly used tools for functional annotation and likely results in much higher specificity. As the authors note, this capability makes the co-occurrence of paralogs, and other divergent genes that share sequence similarity, to contribute less noise (i.e., they result in fewer false positive calls).

It is important to emphasize that these features are not new additions in MacSyFinder v2, but there are many other valuable changes. Most practically, this release is written in Python 3, rather than the obsolete Python 2.7, and was made more computationally efficient, which will enable MacSyFinder to be more widely used and more easily maintained moving forward. In addition, the search algorithm for analyzing individual proteins was fundamentally updated as well. The authors show that their improvements to the search algorithm result in an 8% and 20% increase in the number of identified calls for single and multi-locus secretion systems, respectively. Taken together, MacSyFinder v2 represents both practical and scientific improvements over the previous version, which will be of great value to the field.

References

Abby SS, Néron B, Ménager H, Touchon M, Rocha EPC (2014) MacSyFinder: A Program to Mine Genomes for Molecular Systems with an Application to CRISPR-Cas Systems. PLOS ONE, 9, e110726. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0110726

Altermann E, Tegetmeyer HE, Chanyi RM (2022) The evolution of bacterial genome assemblies - where do we need to go next? Microbiome Research Reports, 1, 15. https://doi.org/10.20517/mrr.2022.02

Douglas GM, Langille MGI (2021) A primer and discussion on DNA-based microbiome data and related bioinformatics analyses. Peer Community Journal, 1. https://doi.org/10.24072/pcjournal.2

Galperin MY, Wolf YI, Makarova KS, Vera Alvarez R, Landsman D, Koonin EV (2021) COG database update: focus on microbial diversity, model organisms, and widespread pathogens. Nucleic Acids Research, 49, D274–D281. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa1018

Néron B, Denise R, Coluzzi C, Touchon M, Rocha EPC, Abby SS (2023) MacSyFinder v2: Improved modelling and search engine to identify molecular systems in genomes. bioRxiv, 2022.09.02.506364, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.02.506364

RAREFAN: A webservice to identify REPINs and RAYTs in bacterial genomes

A workflow for studying enigmatic non-autonomous transposable elements across bacteria

Recommended by Gavin Douglas based on reviews by Sophie Abby and 1 anonymous reviewerRepetitive extragenic palindromic sequences (REPs) are common repetitive elements in bacterial genomes (Gilson et al., 1984; Stern et al., 1984). In 2011, Bertels and Rainey identified that REPs are overrepresented in pairs of inverted repeats, which likely form hairpin structures, that they referred to as “REP doublets forming hairpins” (REPINs). Based on bioinformatics analyses, they argued that REPINs are likely selfish elements that evolved from REPs flanking particular transposes (Bertels and Rainey, 2011). These transposases, so-called REP-associated tyrosine transposases (RAYTs), were known to be highly associated with the REP content in a genome and to have characteristic upstream and downstream flanking REPs (Nunvar et al., 2010). The flanking REPs likely enable RAYT transposition, and their horizontal replication is physically linked to this process. In contrast, Bertels and Rainey hypothesized that REPINs are selfish elements that are highly replicated due to the similarity in arrangement to these RAYT-flanking REPs, but independent of RAYT transposition and generally with no impact on bacterial fitness (Bertels and Rainey, 2011).

This last point was especially contentious, as REPINs are highly conserved within species (Bertels and Rainey, 2023), which is unusual for non-beneficial bacterial DNA (Mira et al., 2001). Bertels and Rainey have since refined their argument to be that REPINs must provide benefits to host cells, but that there are nonetheless signatures of intragenomic conflict in genomes associated with these elements (Bertels and Rainey, 2023). These signatures reflect the divergent levels of selections driving REPIN distribution: selection at the level of each DNA element and selection on each individual bacterium. I found this observation particularly interesting as I and my colleague recently argued that these divergent levels of selection, and the interaction between them, is key to understanding bacterial pangenome diversity (Douglas and Shapiro, 2021). REPINs could be an excellent system for investigating these levels of selection across bacteria more generally.

The problem is that REPINs have not been widely characterized in bacterial genomes, partially because no bioinformatic workflow has been available for this purpose. To address this problem, Fortmann-Grote et al. (2023) developed RAREFAN, which is a web server for identifying RAYTs and associated REPINs in a set of input genomes. The authors showcase their tool by applying it to 49 Stenotrophomonas maltophilia genomes and providing examples of how to identify and assess RAYT-REPIN hits. The workflow requires several manual steps, but nonetheless represents a straightforward and standardized approach. Overall, this workflow should enable RAYTs and REPINs to be identified across diverse bacterial species, which will facilitate further investigation into the mechanisms driving their maintenance and spread.

References

Bertels F, Rainey PB (2023) Ancient Darwinian replicators nested within eubacterial genomes. BioEssays, 45, 2200085. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.202200085

Bertels F, Rainey PB (2011) Within-Genome Evolution of REPINs: a New Family of Miniature Mobile DNA in Bacteria. PLOS Genetics, 7, e1002132. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002132

Douglas GM, Shapiro BJ (2021) Genic Selection Within Prokaryotic Pangenomes. Genome Biology and Evolution, 13, evab234. https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evab234

Fortmann-Grote C, Irmer J von, Bertels F (2023) RAREFAN: A webservice to identify REPINs and RAYTs in bacterial genomes. bioRxiv, 2022.05.22.493013, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.22.493013

Gilson E, Clément J m., Brutlag D, Hofnung M (1984) A family of dispersed repetitive extragenic palindromic DNA sequences in E. coli. The EMBO Journal, 3, 1417–1421. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb01986.x

Mira A, Ochman H, Moran NA (2001) Deletional bias and the evolution of bacterial genomes. Trends in Genetics, 17, 589–596. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9525(01)02447-7

Nunvar J, Huckova T, Licha I (2010) Identification and characterization of repetitive extragenic palindromes (REP)-associated tyrosine transposases: implications for REP evolution and dynamics in bacterial genomes. BMC Genomics, 11, 44. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-11-44

Stern MJ, Ames GF-L, Smith NH, Clare Robinson E, Higgins CF (1984) Repetitive extragenic palindromic sequences: A major component of the bacterial genome. Cell, 37, 1015–1026. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(84)90436-7

EukProt: A database of genome-scale predicted proteins across the diversity of eukaryotes

EukProt enables reproducible Eukaryota-wide protein sequence analyses

Recommended by Gavin Douglas based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers Comparative genomics is a general approach for understanding how genomes differ, which can be considered from many angles. For instance, this approach can delineate how gene content varies across organisms, which can lead to novel hypotheses regarding what those organisms do. It also enables investigations into the sequence-level divergence of orthologous DNA, which can provide insight into how evolutionary forces differentially shape genome content and structure across lineages.

Such comparisons are often restricted to protein-coding genes, as these are sensible units for assessing putative function and for identifying homologous matches in divergent genomes. Although information is lost by focusing only on the protein-coding portion of genomes, this simplifies analyses and has led to crucial findings in recent years. Perhaps most dramatically, analyses based on hundreds of orthologous proteins across microbial eukaryotes are fundamentally changing our understanding of the eukaryotic tree of life (Burki et al. 2020).

These and other topics are highlighted in a new pre-print from Dr. Daniel Richter and colleagues, which describes EukProt (Richter et al. 2022): a database containing protein sets from 993 eukaryotic species. The authors provide a BLAST portal for matching custom sequences against this database (https://evocellbio.com/eukprot/) and the entire database is available for download (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12417881.v3). They also provide a subset of their overall dataset, ‘The Comparative Set’, which contains only high-quality proteomes and is meant to maximize phylogenetic diversity.

There are two major advantages of EukProt:

1. It will enable researchers to quickly compare proteomes and perform phylogenomic analyses, without needing the skills or the time commitment to aggregate and process these data. The authors make it clear that acquiring the raw protein sets was non-trivial, as they were distributed across a wide variety of online repositories (some of which are no longer accessible!).

2. Analyses based on this database will be more reproducible and easily compared across studies than those based on custom-made databases for individual studies. This is because the EukProt authors followed FAIR principles (Wilkinson et al. 2016) when building their database, which is a set of guidelines for enhancing data reusability. So, for instance, each proteome has a unique identifier in EukProt, and all species are annotated in a unified taxonomic framework, which will aid in standardizing comparisons across studies.

The authors make it clear that there is still work to be done. For example, there is an uneven representation of proteomes across different eukaryotic lineages, which can only be addressed by further characterization of poorly studied lineages. In addition, the authors note that it would ultimately be best for the EukProt database to be integrated into an existing large-scale repository, like NCBI, which would help ensure that important eukaryotic diversity was not ignored. Nonetheless, EukProt represents an excellent example of how reproducible bioinformatics resources should be designed and should prove to be an extremely useful resource for the field.

References

Burki F, Roger AJ, Brown MW, Simpson AGB (2020) The New Tree of Eukaryotes. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 35, 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2019.08.008

Richter DJ, Berney C, Strassert JFH, Poh Y-P, Herman EK, Muñoz-Gómez SA, Wideman JG, Burki F, Vargas C de (2022) EukProt: A database of genome-scale predicted proteins across the diversity of eukaryotes. bioRxiv, 2020.06.30.180687, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.30.180687

Wilkinson MD, Dumontier M, Aalbersberg IjJ, Appleton G, Axton M, Baak A, Blomberg N, Boiten J-W, da Silva Santos LB, Bourne PE, Bouwman J, Brookes AJ, Clark T, Crosas M, Dillo I, Dumon O, Edmunds S, Evelo CT, Finkers R, Gonzalez-Beltran A, Gray AJG, Groth P, Goble C, Grethe JS, Heringa J, ’t Hoen PAC, Hooft R, Kuhn T, Kok R, Kok J, Lusher SJ, Martone ME, Mons A, Packer AL, Persson B, Rocca-Serra P, Roos M, van Schaik R, Sansone S-A, Schultes E, Sengstag T, Slater T, Strawn G, Swertz MA, Thompson M, van der Lei J, van Mulligen E, Velterop J, Waagmeester A, Wittenburg P, Wolstencroft K, Zhao J, Mons B (2016) The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data, 3, 160018. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18

Review: 1

A rapid and simple method for assessing and representing genome sequence relatedness

A quick alternative method for resolving bacterial taxonomy using short identical DNA sequences in genomes or metagenomes

Recommended by B. Jesse Shapiro based on reviews by Gavin Douglas and 1 anonymous reviewerThe bacterial species problem can be summarized as follows: bacteria recombine too little, and yet too much (Shapiro 2019).

Too little in the sense that recombination is not obligately coupled with reproduction, as in sexual eukaryotes. So the Biological Species Concept (BSC) of reproductive isolation does not strictly apply to clonally reproducing organisms like bacteria. Too much in the sense that genetic exchange can occur promiscuously across species (or even Domains), potentially obscuring species boundaries.

In parallel to such theoretical considerations, several research groups have taken more pragmatic approaches to defining bacterial species based on sequence similarity cutoffs, such as genome-wide average nucleotide identity (ANI). At a cutoff above 95% ANI, genomes are considered to come from the same species. While this cutoff may appear arbitrary, a discontinuity around 95% in the distribution of ANI values has been argued to provide a 'natural' cutoff (Jain et al. 2018). This discontinuity has been criticized as being an artefact of various biases in genome databases (Murray, Gao, and Wu 2020), but appears to be a general feature of relatively unbiased metagenome-assembled genomes as well (Olm et al. 2020). The 95% cutoff has been suggested to represent a barrier to homologous recombination (Olm et al. 2020), although clusters of genetic exchange consistent with BSC-like species are observed at much finer identity cutoffs (Shapiro 2019; Arevalo et al. 2019).

Although 95% ANI is the most widely used genomic standard for species delimitation, it is by no means the only plausible approach. In particular, tracts of identical DNA provide evidence for recent genetic exchange, which in turn helps define BSC-like clusters of genomes (Arevalo et al. 2019). In this spirit, Briand et al. (2020) introduce a genome-clustering method based on the number of shared identical DNA sequences of length k (or k-mers). Using a test dataset of Pseudomonas genomes, they find that 95% ANI corresponds to approximately 50% of shared 15-mers. Applying this cutoff yields 350 Pseudomonas species, whereas the current taxonomy only includes 207 recognized species. To determine whether splitting the genus into a greater number of species is at all useful, they compare their new classification scheme to the traditional one in terms of the ability to taxonomically classify metagenomic sequencing reads from three Pseudomonas-rich environments. In all cases, the new scheme (termed K-IS for "Kinship relationships Identification with Shared k-mers") yielded a higher number of classified reads, with an average improvement of 1.4-fold. This is important because increasing the number of genome sequences in a reference database – without consistent taxonomic annotation of these genomes – paradoxically leads to fewer classified metagenomic reads. Thus a rapid, automated taxonomy such as the one proposed here offers an opportunity to more fully harness the information from metagenomes.

KI-S is also fast to run, so it is feasible to test several values of k and quickly visualize the clustering using an interactive, zoomable circle-packing display (that resembles a cross-section of densely packed, three-dimensional dendrogram). This interface allows the rapid flagging of misidentified species, or understudied species with few sequenced representatives as targets for future study. Hopefully these initial Pseudomonas results will inspire future studies to apply the method to additional taxa, and to further characterize the relationship between ANI and shared identical k-mers. Ultimately, I hope that such investigations will resolve the issue of whether or not there is a 'natural' discontinuity for bacterial species, and what evolutionary forces maintain this cutoff.

References

Arevalo P, VanInsberghe D, Elsherbini J, Gore J, Polz MF (2019) A Reverse Ecology Approach Based on a Biological Definition of Microbial Populations. Cell, 178, 820-834.e14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2019.06.033

Briand M, Bouzid M, Hunault G, Legeay M, Saux MF-L, Barret M (2020) A rapid and simple method for assessing and representing genome sequence relatedness. bioRxiv, 569640, ver. 5 peer-reveiwed and recommended by PCI Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/569640

Jain C, Rodriguez-R LM, Phillippy AM, Konstantinidis KT, Aluru S (2018) High throughput ANI analysis of 90K prokaryotic genomes reveals clear species boundaries. Nature Communications, 9, 5114. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07641-9

Murray CS, Gao Y, Wu M (2020) There is no evidence of a universal genetic boundary among microbial species. bioRxiv, 2020.07.27.223511. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.27.223511

Olm MR, Crits-Christoph A, Diamond S, Lavy A, Carnevali PBM, Banfield JF (2020) Consistent Metagenome-Derived Metrics Verify and Delineate Bacterial Species Boundaries. mSystems, 5. https://doi.org/10.1128/mSystems.00731-19

Shapiro BJ (2019) What Microbial Population Genomics Has Taught Us About Speciation. In: Population Genomics: Microorganisms Population Genomics. (eds Polz MF, Rajora OP), pp. 31–47. Springer International Publishing, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/13836201810