POLLET Nicolas

- Evolution, Génomes, Comportement, Ecologie, CNRS, Gif-sur-Yvette, France

- Evolutionary genomics, Metagenomics, Vertebrates, Viruses and transposable elements

- recommender

Recommendations: 3

Reviews: 2

Recommendations: 3

Spatio-temporal diversity and genetic architecture of pyrantel resistance in Cylicocyclus nassatus, the most abundant horse parasite

Genomic and transcriptomic insights into the genetic basis of anthelmintic resistance in a cyathostomin parasitic nematode

Recommended by Nicolas Pollet based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersParasitic worms infect billions of animals worldwide. While parasitism is now considered a context-dependent relation along a symbiosis continuum, most of these parasitic worms, also known as helminths, can cause diseases that have a significant impact (Hopkins et al. 2017; Selzer, Epe 2021). When considering livestock animals, these impacts have a high economic cost, and therefore, prophylactic drugs are widely used (Selzer and Epe 2021). Consequently, drug resistance has become increasingly common across all parasites and concerns about drug effects on non-target organisms have been raised (de Souza and Guimarães 2022). This is why understanding the relationship between parasitic worms and their animal hosts and the diseases they cause at the genetic and molecular level is high on the agenda of parasitologists (Doyle 2022). The development of genomics resources plays a pivotal role in this agenda and is at the origin of Sallé and colleagues' article (2025).

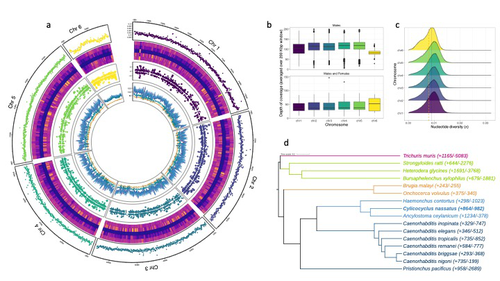

The most common intestinal parasites in equids are helminths of the cyathostomin nematode complex. These are the primary parasitic cause of death in young horses and also exhibit a reduced sensitivity to anthelmintic drugs. Therefore, Sallé and colleagues embarked on the arduous journey to build a reference annotated genome of the Cylicocylus nassatus nematode. They used cutting-edge molecular genetics methods to amplify and sequence the genome of a single individual and obtained chromosomal-level contiguity using Hi-C technology for six chromosomes and an assembly of 514.7 Mbp. Remarkably, transposable elements occupy more than half of the C. nassatus genome and may have led to an increase in genome size in this nematode. In parallel, the authors built a gene catalogue using transcriptomic data, reaching a BUSCO gene completion score of 94.1% with 22,718 protein-coding genes. They quantified allele frequencies based on the resequencing of nine populations, including an ancient Egyptian worm from the 19th century, indicating a recent loss of genetic diversity in European cyathostomin even if geographical sampling was limited. They also analysed transcriptomic differences between sexes and found differences linked with drug treatment. While there may be confounding effects due to global differences between sex that could explain this finding, these results will likely fuel future transcriptomic analyses investigating the response to antiparasitic drugs.

The Cylicocylus nassatus genome assembly obtained will be invaluable for studying nematode genome evolution and analysing the genetic and molecular basis of drug resistance in these parasites.

References

Doyle SR (2022) Improving helminth genome resources in the post-genomic era. Trends in Parasitology, 38, 831–840. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2022.06.002

Hopkins SR, Wojdak JM, Belden LK (2017) Defensive symbionts mediate host–parasite interactions at multiple scales. Trends in Parasitology, 33, 53–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2016.10.003

Sallé G, Courtot É, Cabau C, Parrinello H, Serreau D, Reigner F, Gesbert A, Jacquinot L, Lenhof O, Aimé A, Picandet V, Kuzmina T, Holovachov O, Bellaw J, Nielsen MK, Samson-Himmelstjerna G von, Valière S, Gislard M, Lluch J, Kuchly C, Klopp C (2024) Spatio-temporal diversity and genetic architecture of pyrantel resistance in Cylicocyclus nassatus, the most abundant horse parasite. bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Genomics https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.19.549683

Selzer PM, Epe C (2021) Antiparasitics in animal health: quo vadis? Trends in Parasitology, 37, 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2020.09.004

de Souza RB, Guimarães JR (2022) Effects of avermectins on the environment based on its toxicity to plants and soil invertebrates–a review. Water, Air, and Soil Pollution, 233, 259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-022-05744-0

mbctools: A User-Friendly Metabarcoding and Cross-Platform Pipeline for Analyzing Multiple Amplicon Sequencing Data across a Large Diversity of Organisms

One tool to metabarcode them all

Recommended by Nicolas Pollet based on reviews by Ali Hakimzadeh and Sourakhata TireraOne way to identify all organisms at their various life stages is by their genetic signature. DNA-based taxonomy, gene tagging and barcoding are different shortcuts used to name such strategies (Lamb et al. 2019; Tautz et al. 2003). Reading and analyzing nucleic acid sequences to perform genetic inventories is now faster than ever, and the latest nucleic acid sequencing technologies reveal an impressive taxonomic, genetic, and functional diversity hidden in all ecosystems (Lamb et al. 2019; Sunagawa et al. 2015). This knowledge should enable us to evaluate biodiversity across its scales, from genetic to species to ecosystem and is sometimes referred to with the neologism of ecogenomics (Dicke et al. 2004).

The metabarcoding approach is a key workhorse of ecogenomics. At the core of metabarcoding strategies lies the sequencing of amplicons obtained from so-called multi-template PCR, a formidable and potent experiment with the potential to unravel hidden biosphere components from different samples obtained from organisms or the environment (Kalle et al. 2014; Rodríguez-Ezpeleta et al. 2021). Next to this core approach, and equally important, lies the bioinformatic analysis to convert the raw sequencing data into amplicon sequence variants or operational taxonomic units and interpretable abundance tables.

Methodologically, the analysis of sequences obtained from metabarcoding projects is replete with devilish details. This is why different pipelines and tools have been developed, starting with mothur (Schloss et al. 2009) and QIIME 2 (Bolyen et al. 2019), but including more user friendly tools such as FROGS (Escudié et al. 2018). Yet, across all available tools, scientists must choose the optimal algorithms and parameter values to filter raw reads, trim primers, identify chimeras and cluster reads into operational taxonomic units. In addition, the number of genetic markers used to characterize a sample using metabarcoding has increased as sequencing methods are now less costly and more efficient. In such cases, results and interpretations may become limited or confounded. This is where the novel tools proposed by Barnabé and colleagues (2024), mbctools, will benefit researchers in this field.

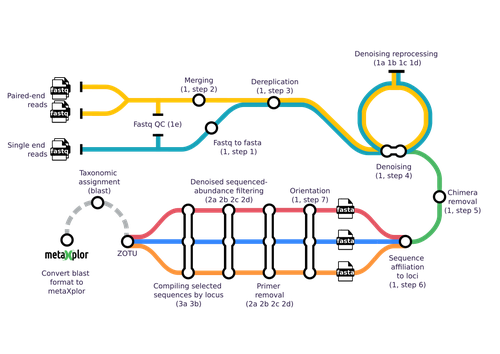

The authors provide a detailed description with a walk-through of the mbctools pipeline to analyse raw reads obtained in a metabarcoding project. The mbctools pipeline can be installed under different computing environments, requires only VSEARCH and a few Python dependencies, and is easy to use with a menu-driven interface. Users need to prepare their data following simple rules, providing single or paired-end reads, primer and target database sequences. An interesting feature of mbctools output is the possibility of integration with the metaXplor visualization tool developed by the authors (Sempéré et al. 2021). As it stands, mbctools should be used for short-read sequences. The taxonomy assignment module has the advantage to enable parameters exploration in an easy way, but it may be oversimplistic for specific taxa.

The lightweight aspect of mbctools and its overall simplicity are appealing. These features will make it a useful pipeline for training workshops and to help disseminate the use of metabarcoding. It also holds the potential for further improvement, by the developers or by others. In the end, mbctools will support study reproducibility by enabling a streamlined analysis of raw reads, and like many useful tools, only time will tell whether it is widely adopted.

References

Barnabé C, Sempéré G, Manzanilla V, Millan JM, Amblard-Rambert A, Waleckx E (2024) mbctools: A user-friendly metabarcoding and cross-platform pipeline for analyzing multiple amplicon sequencing data across a large diversity of organisms. bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Genomics https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.02.08.579441

Bolyen E, Rideout JR, Dillon MR, Bokulich NA, et al. (2019) Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nature Biotechnology, 37, 852–857. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0209-9

Dicke M, van Loon JJA, de Jong PW (2004) Ecogenomics benefits community ecology. Science, 305, 618–619. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1101788

Escudié F, Auer L, Bernard M, Mariadassou M, Cauquil L, Vidal K, Maman S, Hernandez-Raquet G, Combes S, Pascal G (2018) FROGS: Find, Rapidly, OTUs with Galaxy Solution. Bioinformatics, 34, 1287-1294. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btx791

Kalle E, Kubista M, Rensing C (2014) Multi-template polymerase chain reaction. Biomolecular Detection and Quantification, 2, 11–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bdq.2014.11.002

Lamb CT, Ford AT, Proctor MF, Royle JA, Mowat G, Boutin S (2019) Genetic tagging in the Anthropocene: scaling ecology from alleles to ecosystems. Ecological Applications, 29, e01876. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.1876

Rodríguez-Ezpeleta N, Zinger L, Kinziger A, Bik HM, Bonin A, Coissac E, Emerson BC, Lopes CM, Pelletier TA, Taberlet P, Narum S (2021) Biodiversity monitoring using environmental DNA. Molecular Ecology Resources, 21, 1405–1409. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13399

Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, Hall JR, Hartmann M, Hollister EB, Lesniewski RA, Oakley BB, Parks DH, Robinson CJ, Sahl JW, Stres B, Thallinger GG, Van Horn DJ, Weber CF (2009) Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 75, 7537-41. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01541-09

Sempéré G, Pétel A, Abbé M, Lefeuvre P, Roumagnac P, Mahé F, Baurens G, Filloux D 2021 metaXplor: an interactive viral and microbial metagenomic data manager. Gigascience, 10, https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giab001

Sunagawa S, Coelho LP, Chaffron S, Kultima JR, Labadie K, Salazar G, Djahanschiri B, Zeller G, Mende DR, Alberti A, Cornejo-Castillo FM, Costea PI, Cruaud C, d’Ovidio F, Engelen S, Ferrera I, Gasol JM, Guidi L, Hildebrand F, Kokoszka F, Lepoivre C, Lima-Mendez G, Poulain J, Poulos BT, Royo-Llonch M, Sarmento H, Vieira-Silva S, Dimier C, Picheral M, Searson S, Kandels-Lewis S, Tara Oceans coordinators, Bowler C, de Vargas C, Gorsky G, Grimsley N, Hingamp P, Iudicone D, Jaillon O, Not F, Ogata H, Pesant S, Speich S, Stemmann L, Sullivan MB, Weissenbach J, Wincker P, Karsenti E, Raes J, Acinas SG, Bork P (2015) Structure and function of the global ocean microbiome. Science, 348, 1261359. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1261359

Tautz D, Arctander P, Minelli A, Thomas RH, Vogler AP (2003) A plea for DNA taxonomy. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 18, 70–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-5347(02)00041-1

Identification and quantification of transposable element transcripts using Long-Read RNA-seq in Drosophila germline tissues

Unveiling transposon dynamics: Advancing TE expression analysis in Drosophila with long-read sequencing

Recommended by Nicolas Pollet based on reviews by Silke Jensen, Christophe Antoniewski and 1 anonymous reviewerTransposable elements (TEs) are mobile genetic elements with an intrinsic mutagenic potential that influences the physiology of any cell type, whether somatic or germinal. Measuring TE expression is a fundamental prerequisite for analysing the processes leading to the activity of TE-derived sequences. This applies to both old and recent TEs, as even if they are deficient in mobilisation, transcription of TE sequences alone can impact neighbouring gene expression and other cellular activities.

In terms of TE physiology, transcription is crucial for mobilisation activity. The transcription of some TEs can be tissue-specific and associated with splicing events, as exemplified by the P-element isoforms in the fruit fly (Laski et al. 1986). Regarding host cell physiology, TE transcripts can include nearby exons, with or without splicing, and such chimeric transcripts can significantly alter gene activity. Thus, quantitative and qualitative analyses must be conducted to assess TE function and how they can modify genomic activities. Yet, due to the polymorphic, interspersed, and repetitive nature of TE sequences, the quantitative and qualitative analysis of TE transcript levels using short-read sequencing remains challenging (Lanciano and Cristofari 2020).

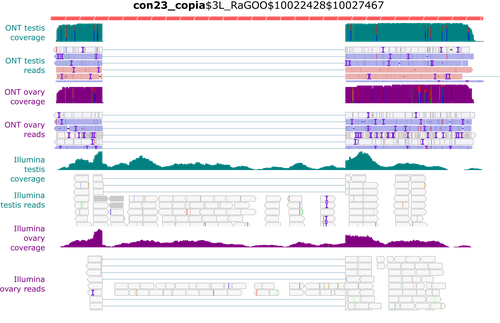

In this context, Rebollo et al. (2024) employed nanopore long-read sequencing to analyse cDNAs derived from Drosophila melanogaster germline RNAs. The authors constructed two long-read cDNA libraries from pooled ovaries and testes using a protocol to obtain full-length cDNAs and sequenced them separately. They carefully compared their results with their short-read datasets. Overall, their observations corroborate known patterns of germline-specific expression of certain TEs and provide initial evidence of novel spliced TE transcript isoforms in Drosophila.

Rebollo and colleagues have provided a well-documented and detailed analysis of their results, which will undoubtedly benefit the scientific community. They presented the challenges and limitations of their approach, such as the length of the transcripts, and provided a reproducible analysis workflow that will enable better characterisation of TE expression using long-read technology.

Despite the small number of samples and limited sequencing depth, this pioneering study strikingly demonstrates the potential of long-read sequencing for the quantitative and qualitative analysis of TE transcription, a technology that will facilitate a better understanding of the transposon landscape.

References

Lanciano S, Cristofari G (2020) Measuring and interpreting transposable element expression. Nature Reviews Genetics, 21, 721–736. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-020-0251-y

Laski FA, Rio DC, Rubin GM (1986) Tissue specificity of Drosophila P element transposition is regulated at the level of mRNA splicing. Cell, 44, 7–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(86)90480-0

Rebollo R, Gerenton P, Cumunel E, Mary A, Sabot F, Burlet N, Gillet B, Hughes S, Oliveira DS, Goubert C, Fablet M, Vieira C, Lacroix V (2024) Identification and quantification of transposable element transcripts using Long-Read RNA-seq in Drosophila germline tissues. bioRxiv, ver.4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.27.542554

Reviews: 2

Genomic data suggest parallel dental vestigialization within the xenarthran radiation

What does dental gene decay tell us about the regressive evolution of teeth in South American mammals?

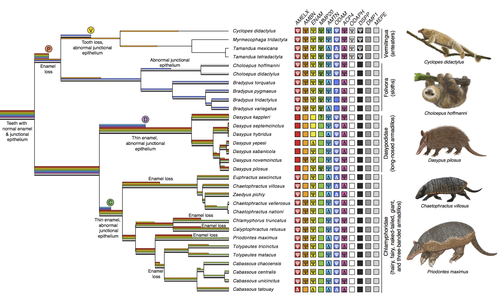

Recommended by Didier Casane based on reviews by Juan C. Opazo, Régis Debruyne and Nicolas PolletA group of mammals, Xenathra, evolved and diversified in South America during its long period of isolation in the early to mid Cenozoic era. More recently, as a result of the Great Faunal Interchange between South America and North America, many xenarthran species went extinct. The thirty-one extant species belong to three groups: armadillos, sloths and anteaters. They share dental degeneration. However, the level of degeneration is variable. Anteaters entirely lack teeth, sloths have intermediately regressed teeth and most armadillos have a toothless premaxilla, as well as peg-like, single-rooted teeth that lack enamel in adult animals (Vizcaíno 2009). This diversity raises a number of questions about the evolution of dentition in these mammals. Unfortunately, the fossil record is too poor to provide refined information on the different stages of regressive evolution in these clades. In such cases, the identification of loss-of-function mutations and/or relaxed selection in genes related to a character regression can be very informative (Emerling and Springer 2014; Meredith et al. 2014; Policarpo et al. 2021). Indeed, shared and unique pseudogenes/relaxed selection can tell us to what extent regression has occurred in common ancestors and whether some changes are lineage-specific. In addition, the distribution of pseudogenes/relaxed selection on the branches of a phylogenetic tree is related to the evolutionary processes involved. A much higher density of pseudogenes in the most internal branches indicates that degeneration took place early and over a short period of time, consistent with selection against the presence of the morphological character with which they are associated, while pseudogenes distributed evenly in many internal and external branches suggest a more gradual process over many millions of years, in line with relaxed selection and fixation of loss-of-function mutations by genetic drift.

In this paper (Emerling et al. 2023), the authors examined the dynamics of decay of 11 dental genes that may parallel teeth regression. The analyses of the data reported in this paper clearly point to xenarthran teeth having repeatedly regressed in parallel in the three clades. In fact, no loss-of-function mutation is shared by all species examined. However, more genes should be studied to confirm the hypothesis that the common ancestor of extant xenarthrans had normal dentition. There are distinct patterns of gene loss in different lineages that are associated with the variation in dentition observed across the clades. These patterns of gene loss suggest that regressive evolution took place both gradually and in relatively rapid, discrete phases during the diversification of xenarthrans. This study underscores the utility of using pseudogenes to reconstruct evolutionary history of morphological characters when fossils are sparse.

References

Emerling CA, Gibb GC, Tilak M-K, Hughes JJ, Kuch M, Duggan AT, Poinar HN, Nachman MW, Delsuc F. 2023. Genomic data suggest parallel dental vestigialization within the xenarthran radiation. bioRxiv, 2022.12.09.519446, ver 2, peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.09.519446

Emerling CA, Springer MS. 2014. Eyes underground: Regression of visual protein networks in subterranean mammals. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 78: 260-270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2014.05.016

Meredith RW, Zhang G, Gilbert MTP, Jarvis ED, Springer MS. 2014. Evidence for a single loss of mineralized teeth in the common avian ancestor. Science 346: 1254390. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1254390

Policarpo M, Fumey J, Lafargeas P, Naquin D, Thermes C, Naville M, Dechaud C, Volff J-N, Cabau C, Klopp C, et al. 2021. Contrasting gene decay in subterranean vertebrates: insights from cavefishes and fossorial mammals. Molecular Biology and Evolution 38: 589-605. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msaa249

Vizcaíno SF. 2009. The teeth of the “toothless”: novelties and key innovations in the evolution of xenarthrans (Mammalia, Xenarthra). Paleobiology 35: 343-366. https://doi.org/10.1666/0094-8373-35.3.343

A primer and discussion on DNA-based microbiome data and related bioinformatics analyses

A hitchhiker’s guide to DNA-based microbiome analysis

Recommended by Danny Ionescu based on reviews by Nicolas Pollet, Rafael Cuadrat and 1 anonymous reviewerIn the last two decades, microbial research in its different fields has been increasingly focusing on microbiome studies. These are defined as studies of complete assemblages of microorganisms in given environments and have been benefiting from increases in sequencing length, quality, and yield, coupled with ever-dropping prices per sequenced nucleotide. Alongside localized microbiome studies, several global collaborative efforts have emerged, including the Human Microbiome Project [1], the Earth Microbiome Project [2], the Extreme Microbiome Project, and MetaSUB [3].

Coupled with the development of sequencing technologies and the ever-increasing amount of data output, multiple standalone or online bioinformatic tools have been designed to analyze these data. Often these tools have been focusing on either of two main tasks: 1) Community analysis, providing information on the organisms present in the microbiome, or 2) Functionality, in the case of shotgun metagenomic data, providing information on the metabolic potential of the microbiome. Bridging between the two types of data, often extracted from the same dataset, is typically a daunting task that has been addressed by a handful of tools only.

The extent of tools and approaches to analyze microbiome data is great and may be overwhelming to researchers new to microbiome or bioinformatic studies. In their paper “A primer and discussion on DNA-based microbiome data and related bioinformatics analyses”, Douglas and Langille [4] guide us through the different sequencing approaches useful for microbiome studies. alongside their advantages and caveats and a selection of tools to analyze these data, coupled with examples from their own field of research.

Standing out in their primer-style review is the emphasis on the coupling between taxonomic/phylogenetic identification of the organisms and their functionality. This type of analysis, though highly important to understand the role of different microorganisms in an environment as well as to identify potential functional redundancy, is often not conducted. For this, the authors identify two approaches. The first, using shotgun metagenomics, has higher chances of attributing a function to the correct taxon. The second, using amplicon sequencing of marker genes, allows for a deeper coverage of the microbiome at a lower cost, and extrapolates the amplicon data to close relatives with a sequenced genome. As clearly stated, this approach makes the leap between taxonomy and functionality and has been shown to be erroneous in cases where the core genome of the bacterial genus or family does not encompass the functional diversity of the different included species. This practice was already common before the genomic era, but its accuracy is improving thanks to the increasing availability of sequenced reference genomes from cultures, environmentally picked single cells or metagenome-assembled genome.

In addition to their description of standalone tools useful for linking taxonomy and functionality, one should mention the existence of online tools that may appeal to researchers who do not have access to adequate bioinformatics infrastructure. Among these are the Integrated Microbial Genomes and Microbiomes (IMG) from the Joint Genome Institute [5], KBase [6] and MG-RAST [7].

A second important point arising from this review is the need for standardization in microbiome data analyses and the complexity of achieving this. As Douglas and Langille [4] state, this has been previously addressed, highlighting the variability in results obtained with different tools. It is often the case that papers describing new bioinformatic tools display their superiority relative to existing alternatives, potentially misleading newcomers to the field that the newest tool is the best and only one to be used. This is often not the case, and while benchmarking against well-defined datasets serves as a powerful testing tool, “real-life” samples are often not comparable. Thus, as done here, future primer-like reviews should highlight possible cross-field caveats, encouraging researchers to employ and test several approaches and validate their results whenever possible.

In summary, Douglas and Langille [4] offer both the novice and experienced researcher a detailed guide along the paths of microbiome data analysis, accompanied by informative background information, suggested tools with which analyses can be started, and an insightful view on where the field should be heading.

References

[1] Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Hamady M, Fraser-Liggett CM, Knight R, Gordon JI (2007) The Human Microbiome Project. Nature, 449, 804–810. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06244

[2] Gilbert JA, Jansson JK, Knight R (2014) The Earth Microbiome project: successes and aspirations. BMC Biology, 12, 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-014-0069-1

[3] Mason C, Afshinnekoo E, Ahsannudin S, Ghedin E, Read T, Fraser C, Dudley J, Hernandez M, Bowler C, Stolovitzky G, Chernonetz A, Gray A, Darling A, Burke C, Łabaj PP, Graf A, Noushmehr H, Moraes s., Dias-Neto E, Ugalde J, Guo Y, Zhou Y, Xie Z, Zheng D, Zhou H, Shi L, Zhu S, Tang A, Ivanković T, Siam R, Rascovan N, Richard H, Lafontaine I, Baron C, Nedunuri N, Prithiviraj B, Hyat S, Mehr S, Banihashemi K, Segata N, Suzuki H, Alpuche Aranda CM, Martinez J, Christopher Dada A, Osuolale O, Oguntoyinbo F, Dybwad M, Oliveira M, Fernandes A, Oliveira M, Fernandes A, Chatziefthimiou AD, Chaker S, Alexeev D, Chuvelev D, Kurilshikov A, Schuster S, Siwo GH, Jang S, Seo SC, Hwang SH, Ossowski S, Bezdan D, Udekwu K, Udekwu K, Lungjdahl PO, Nikolayeva O, Sezerman U, Kelly F, Metrustry S, Elhaik E, Gonnet G, Schriml L, Mongodin E, Huttenhower C, Gilbert J, Hernandez M, Vayndorf E, Blaser M, Schadt E, Eisen J, Beitel C, Hirschberg D, Schriml L, Mongodin E, The MetaSUB International Consortium (2016) The Metagenomics and Metadesign of the Subways and Urban Biomes (MetaSUB) International Consortium inaugural meeting report. Microbiome, 4, 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-016-0168-z

[4] Douglas GM, Langille MGI (2021) A primer and discussion on DNA-based microbiome data and related bioinformatics analyses. OSF Preprints, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Genomics. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/3dybg

[5] Chen I-MA, Markowitz VM, Chu K, Palaniappan K, Szeto E, Pillay M, Ratner A, Huang J, Andersen E, Huntemann M, Varghese N, Hadjithomas M, Tennessen K, Nielsen T, Ivanova NN, Kyrpides NC (2017) IMG/M: integrated genome and metagenome comparative data analysis system. Nucleic Acids Research, 45, D507–D516. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw929

[6] Arkin AP, Cottingham RW, Henry CS, Harris NL, Stevens RL, Maslov S, Dehal P, Ware D, Perez F, Canon S, Sneddon MW, Henderson ML, Riehl WJ, Murphy-Olson D, Chan SY, Kamimura RT, Kumari S, Drake MM, Brettin TS, Glass EM, Chivian D, Gunter D, Weston DJ, Allen BH, Baumohl J, Best AA, Bowen B, Brenner SE, Bun CC, Chandonia J-M, Chia J-M, Colasanti R, Conrad N, Davis JJ, Davison BH, DeJongh M, Devoid S, Dietrich E, Dubchak I, Edirisinghe JN, Fang G, Faria JP, Frybarger PM, Gerlach W, Gerstein M, Greiner A, Gurtowski J, Haun HL, He F, Jain R, Joachimiak MP, Keegan KP, Kondo S, Kumar V, Land ML, Meyer F, Mills M, Novichkov PS, Oh T, Olsen GJ, Olson R, Parrello B, Pasternak S, Pearson E, Poon SS, Price GA, Ramakrishnan S, Ranjan P, Ronald PC, Schatz MC, Seaver SMD, Shukla M, Sutormin RA, Syed MH, Thomason J, Tintle NL, Wang D, Xia F, Yoo H, Yoo S, Yu D (2018) KBase: The United States Department of Energy Systems Biology Knowledgebase. Nature Biotechnology, 36, 566–569. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.4163

[7] Wilke A, Bischof J, Gerlach W, Glass E, Harrison T, Keegan KP, Paczian T, Trimble WL, Bagchi S, Grama A, Chaterji S, Meyer F (2016) The MG-RAST metagenomics database and portal in 2015. Nucleic Acids Research, 44, D590–D594. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv1322