Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract▼ | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

06 Jul 2021

A pipeline to detect the relationship between transposable elements and adjacent genes in host genomesCaroline Meguerditchian, Ayse Ergun, Veronique Decroocq, Marie Lefebvre, Quynh-Trang Bui https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.25.432867A new tool to cross and analyze TE and gene annotationsRecommended by Emmanuelle Lerat based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersTransposable elements (TEs) are important components of genomes. Indeed, they are now recognized as having a major role in gene and genome evolution (Biémont 2010). In particular, several examples have shown that the presence of TEs near genes may influence their functioning, either by recruiting particular epigenetic modifications (Guio et al. 2018) or by directly providing new regulatory sequences allowing new expression patterns (Chung et al. 2007; Sundaram et al. 2014). Therefore, the study of the interaction between TEs and their host genome requires tools to easily cross-annotate both types of entities. In particular, one needs to be able to identify all TEs located in the close vicinity of genes or inside them. Such task may not always be obvious for many biologists, as it requires informatics knowledge to develop their own script codes. In their work, Meguerdichian et al. (2021) propose a command-line pipeline that takes as input the annotations of both genes and TEs for a given genome, then detects and reports the positional relationships between each TE insertion and their closest genes. The results are processed into an R script to provide tables displaying some statistics and graphs to visualize these relationships. This tool has the potential to be very useful for performing preliminary analyses before studying the impact of TEs on gene functioning, especially for biologists. Indeed, it makes it possible to identify genes close to TE insertions. These identified genes could then be specifically considered in order to study in more detail the link between the presence of TEs and their functioning. For example, the identification of TEs close to genes may allow to determine their potential role on gene expression. References Biémont C (2010). A brief history of the status of transposable elements: from junk DNA to major players in evolution. Genetics, 186, 1085–1093. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.110.124180 Chung H, Bogwitz MR, McCart C, Andrianopoulos A, ffrench-Constant RH, Batterham P, Daborn PJ (2007). Cis-regulatory elements in the Accord retrotransposon result in tissue-specific expression of the Drosophila melanogaster insecticide resistance gene Cyp6g1. Genetics, 175, 1071–1077. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.106.066597 Guio L, Vieira C, González J (2018). Stress affects the epigenetic marks added by natural transposable element insertions in Drosophila melanogaster. Scientific Reports, 8, 12197. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-30491-w Meguerditchian C, Ergun A, Decroocq V, Lefebvre M, Bui Q-T (2021). A pipeline to detect the relationship between transposable elements and adjacent genes in host genomes. bioRxiv, 2021.02.25.432867, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.25.432867 Sundaram V, Cheng Y, Ma Z, Li D, Xing X, Edge P, Snyder MP, Wang T (2014). Widespread contribution of transposable elements to the innovation of gene regulatory networks. Genome Research, 24, 1963–1976. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.168872.113 | A pipeline to detect the relationship between transposable elements and adjacent genes in host genomes | Caroline Meguerditchian, Ayse Ergun, Veronique Decroocq, Marie Lefebvre, Quynh-Trang Bui | <p>Understanding the relationship between transposable elements (TEs) and their closest positional genes in the host genome is a key point to explore their potential role in genome evolution. Transposable elements can regulate and affect gene expr... |  | Bioinformatics, Viruses and transposable elements | Emmanuelle Lerat | 2021-03-03 15:08:34 | View | |

18 Feb 2021

Traces of transposable element in genome dark matter co-opted by flowering gene regulation networksAgnes Baud, Mariene Wan, Danielle Nouaud, Nicolas Francillonne, Dominique Anxolabehere, Hadi Quesneville https://doi.org/10.1101/547877Using small fragments to discover old TE remnants: the Duster approach empowers the TE detectionRecommended by Francois Sabot based on reviews by Josep Casacuberta and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Josep Casacuberta and 1 anonymous reviewer

Transposable elements are the raw material of the dark matter of the genome, the foundation of the next generation of genes and regulation networks". This sentence could be the essence of the paper of Baud et al. (2021). Transposable elements (TEs) are endogenous mobile genetic elements found in almost all genomes, which were discovered in 1948 by Barbara McClintock (awarded in 1983 the only unshared Medicine Nobel Prize so far). TEs are present everywhere, from a single isolated copy for some elements to more than millions for others, such as Alu. They are founders of major gene lineages (HET-A, TART and telomerases, RAG1/RAG2 proteins from mammals immune system; Diwash et al, 2017), and even of retroviruses (Xiong & Eickbush, 1988). However, most TEs appear as selfish elements that replicate, land in a new genomic region, then start to decay and finally disappear in the midst of the genome, turning into genomic ‘dark matter’ (Vitte et al, 2007). The mutations (single point, deletion, recombination, and so on) that occur during this slow death erase some of their most notable features and signature sequences, rendering them completely unrecognizable after a few million years. Numerous TE detection tools have tried to optimize their detection (Goerner-Potvin & Bourque, 2018), but further improvement is definitely challenging. This is what Baud et al. (2021) accomplished in their paper. They used a simple, elegant and efficient k-mer based approach to find small signatures that, when accumulated, allow identifying very old TEs. Using this method, called Duster, they improved the amount of annotated TEs in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana by 20%, pushing the part of this genome occupied by TEs up from 40 to almost 50%. They further observed that these very old Duster-specific TEs (i.e., TEs that are only detected by Duster) are, among other properties, close to genes (much more than recent TEs), not targeted by small RNA pathways, and highly associated with conserved regions across the rosid family. In addition, they are highly associated with flowering or stress response genes, and may be involved through exaptation in the evolution of responses to environmental changes. TEs are not just selfish elements: more and more studies have shown their key role in the evolution of their hosts, and tools such as Duster will help us better understand their impact. References Baud, A., Wan, M., Nouaud, D., Francillonne, N., Anxolabéhère, D. and Quesneville, H. (2021). Traces of transposable elements in genome dark matter co-opted by flowering gene regulation networks. bioRxiv, 547877, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Genomics.doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/547877 | Traces of transposable element in genome dark matter co-opted by flowering gene regulation networks | Agnes Baud, Mariene Wan, Danielle Nouaud, Nicolas Francillonne, Dominique Anxolabehere, Hadi Quesneville | <p>Transposable elements (TEs) are mobile, repetitive DNA sequences that make the largest contribution to genome bulk. They thus contribute to the so-called 'dark matter of the genome', the part of the genome in which nothing is immediately recogn... |  | Bioinformatics, Evolutionary genomics, Functional genomics, Plants, Structural genomics, Viruses and transposable elements | Francois Sabot | Anonymous, Josep Casacuberta | 2020-04-07 17:12:12 | View |

02 Apr 2021

Semi-artificial datasets as a resource for validation of bioinformatics pipelines for plant virus detectionLucie Tamisier, Annelies Haegeman, Yoika Foucart, Nicolas Fouillien, Maher Al Rwahnih, Nihal Buzkan, Thierry Candresse, Michela Chiumenti, Kris De Jonghe, Marie Lefebvre, Paolo Margaria, Jean Sébastien Reynard, Kristian Stevens, Denis Kutnjak, Sébastien Massart https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4584718Toward a critical assessment of virus detection in plantsRecommended by Hadi Quesneville based on reviews by Alexander Suh and 1 anonymous reviewerThe advent of High Throughput Sequencing (HTS) since the last decade has revealed previously unsuspected diversity of viruses as well as their (sometimes) unexpected presence in some healthy individuals. These results demonstrate that genomics offers a powerful tool for studying viruses at the individual level, allowing an in-depth inventory of those that are infecting an organism. Such approaches make it possible to study viromes with an unprecedented level of detail, both qualitative and quantitative, which opens new venues for analyses of viruses of humans, animals and plants. Consequently, the diagnostic field is using more and more HTS, fueling the need for efficient and reliable bioinformatics tools. Many such tools have already been developed, but in plant disease diagnostics, validation of the bioinformatics pipelines used for the detection of viruses in HTS datasets is still in its infancy. There is an urgent need for benchmarking the different tools and algorithms using well-designed reference datasets generated for this purpose. This is a crucial step to move forward and to improve existing solutions toward well-standardized bioinformatics protocols. This context has led to the creation of the Plant Health Bioinformatics Network (PHBN), a Euphresco network project aiming to build a bioinformatics community working on plant health. One of their objectives is to provide researchers with open-access reference datasets allowing to compare and validate virus detection pipelines. In this framework, Tamisier et al. [1] present real, semi-artificial, and completely artificial datasets, each aimed at addressing challenges that could affect virus detection. These datasets comprise real RNA-seq reads from virus-infected plants as well as simulated virus reads. Such a work, providing open-access datasets for benchmarking bioinformatics tools, should be encouraged as they are key to software improvement as demonstrated by the well-known success story of the protein structure prediction community: their pioneer community-wide effort, called Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP)[2], has been providing research groups since 1994 with an invaluable way to objectively test their structure prediction methods, thereby delivering an independent assessment of state-of-art protein-structure modelling tools. Following this success, many other bioinformatic community developed similar “competitions”, such as RNA-puzzles [3] to predict RNA structures, Critical Assessment of Function Annotation [4] to predict gene functions, Critical Assessment of Prediction of Interactions [5] to predict protein-protein interactions, Assemblathon [6] for genome assembly, etc. These are just a few examples from a long list of successful initiatives. Such efforts enable rigorous assessments of tools, stimulate the developers’ creativity, but also provide user communities with a state-of-art evaluation of available tools. Inspired by these success stories, the authors propose a “VIROMOCK challenge” [7], asking researchers in the field to test their tools and to provide feedback on each dataset through a repository. This initiative, if well followed, will undoubtedly improve the field of virus detection in plants, but also probably in many other organisms. This will be a major contribution to the field of viruses, leading to better diagnostics and, consequently, a better understanding of viral diseases, thus participating in promoting human, animal and plant health. References [1] Tamisier, L., Haegeman, A., Foucart, Y., Fouillien, N., Al Rwahnih, M., Buzkan, N., Candresse, T., Chiumenti, M., De Jonghe, K., Lefebvre, M., Margaria, P., Reynard, J.-S., Stevens, K., Kutnjak, D. and Massart, S. (2021) Semi-artificial datasets as a resource for validation of bioinformatics pipelines for plant virus detection. Zenodo, 4273791, version 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Genomics. doi: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4273791 [2] Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction” (CASP) - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CASP [3] RNA-puzzles - https://www.rnapuzzles.org [4] Critical Assessment of Function Annotation (CAFA) - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Critical_Assessment_of_Function_Annotation [5] Critical Assessment of Prediction of Interactions (CAPI) - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Critical_Assessment_of_Prediction_of_Interactions [6] Assemblathon - https://assemblathon.org [7] VIROMOCK challenge - https://gitlab.com/ilvo/VIROMOCKchallenge | Semi-artificial datasets as a resource for validation of bioinformatics pipelines for plant virus detection | Lucie Tamisier, Annelies Haegeman, Yoika Foucart, Nicolas Fouillien, Maher Al Rwahnih, Nihal Buzkan, Thierry Candresse, Michela Chiumenti, Kris De Jonghe, Marie Lefebvre, Paolo Margaria, Jean Sébastien Reynard, Kristian Stevens, Denis Kutnjak, Séb... | <p>The widespread use of High-Throughput Sequencing (HTS) for detection of plant viruses and sequencing of plant virus genomes has led to the generation of large amounts of data and of bioinformatics challenges to process them. Many bioinformatics... |  | Bioinformatics, Plants, Viruses and transposable elements | Hadi Quesneville | 2020-11-27 14:31:47 | View | |

23 Sep 2022

MATEdb, a data repository of high-quality metazoan transcriptome assemblies to accelerate phylogenomic studiesRosa Fernandez, Vanina Tonzo, Carolina Simon Guerrero, Jesus Lozano-Fernandez, Gemma I Martinez-Redondo, Pau Balart-Garcia, Leandro Aristide, Klara Eleftheriadi, Carlos Vargas-Chavez https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.18.500182MATEdb: a new phylogenomic-driven database for MetazoaRecommended by Samuel Abalde based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

The development (and standardization) of high-throughput sequencing techniques has revolutionized evolutionary biology, to the point that we almost see as normal fine-detail studies of genome architecture evolution (Robert et al., 2022), adaptation to new habitats (Rahi et al., 2019), or the development of key evolutionary novelties (Hilgers et al., 2018), to name three examples. One of the fields that has benefited the most is phylogenomics, i.e. the use of genome-wide data for inferring the evolutionary relationships among organisms. Dealing with such amount of data, however, has come with important analytical and computational challenges. Likewise, although the steady generation of genomic data from virtually any organism opens exciting opportunities for comparative analyses, it also creates a sort of “information fog”, where it is hard to find the most appropriate and/or the higher quality data. I have personally experienced this not so long ago, when I had to spend several weeks selecting the most complete transcriptomes from several phyla, moving back and forth between the NCBI SRA repository and the relevant literature. In an attempt to deal with this issue, some research labs have committed their time and resources to the generation of taxa- and topic-specific databases (Lathe et al., 2008), such as MolluscDB (Liu et al., 2021), focused on mollusk genomics, or EukProt (Richter et al., 2022), a protein repository representing the diversity of eukaryotes. A new database that promises to become an important resource in the near future is MATEdb (Fernández et al., 2022), a repository of high-quality genomic data from Metazoa. MATEdb has been developed from publicly available and newly generated transcriptomes and genomes, prioritizing quality over quantity. Upon download, the user has access to both raw data and the related datasets: assemblies, several quality metrics, the set of inferred protein-coding genes, and their annotation. Although it is clear to me that this repository has been created with phylogenomic analyses in mind, I see how it could be generalized to other related problems such as analyses of gene content or evolution of specific gene families. In my opinion, the main strengths of MATEdb are threefold:

On a negative note, I see two main drawbacks. First, as of today (September 16th, 2022) this database is in an early stage and it still needs to incorporate a lot of animal groups. This has been discussed during the revision process and the authors are already working on it, so it is only a matter of time until all major taxa are represented. Second, there is a scalability issue. In its current format it is not possible to select the taxa of interest and the full database has to be downloaded, which will become more and more difficult as it grows. Nonetheless, with the appropriate resources it would be easy to find a better solution. There are plenty of examples that could serve as inspiration, so I hope this does not become a big problem in the future. Altogether, I and the researchers that participated in the revision process believe that MATEdb has the potential to become an important and valuable addition to the metazoan phylogenomics community. Personally, I wish it was available just a few months ago, it would have saved me so much time. References Fernández R, Tonzo V, Guerrero CS, Lozano-Fernandez J, Martínez-Redondo GI, Balart-García P, Aristide L, Eleftheriadi K, Vargas-Chávez C (2022) MATEdb, a data repository of high-quality metazoan transcriptome assemblies to accelerate phylogenomic studies. bioRxiv, 2022.07.18.500182, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.18.500182 Hilgers L, Hartmann S, Hofreiter M, von Rintelen T (2018) Novel Genes, Ancient Genes, and Gene Co-Option Contributed to the Genetic Basis of the Radula, a Molluscan Innovation. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 35, 1638–1652. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy052 Lathe W, Williams J, Mangan M, Karolchik, D (2008). Genomic data resources: challenges and promises. Nature Education, 1(3), 2. Liu F, Li Y, Yu H, Zhang L, Hu J, Bao Z, Wang S (2021) MolluscDB: an integrated functional and evolutionary genomics database for the hyper-diverse animal phylum Mollusca. Nucleic Acids Research, 49, D988–D997. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa918 Rahi ML, Mather PB, Ezaz T, Hurwood DA (2019) The Molecular Basis of Freshwater Adaptation in Prawns: Insights from Comparative Transcriptomics of Three Macrobrachium Species. Genome Biology and Evolution, 11, 1002–1018. https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evz045 Richter DJ, Berney C, Strassert JFH, Poh Y-P, Herman EK, Muñoz-Gómez SA, Wideman JG, Burki F, Vargas C de (2022) EukProt: A database of genome-scale predicted proteins across the diversity of eukaryotes. bioRxiv, 2020.06.30.180687, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.30.180687 Robert NSM, Sarigol F, Zimmermann B, Meyer A, Voolstra CR, Simakov O (2022) Emergence of distinct syntenic density regimes is associated with early metazoan genomic transitions. BMC Genomics, 23, 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-022-08304-2 | MATEdb, a data repository of high-quality metazoan transcriptome assemblies to accelerate phylogenomic studies | Rosa Fernandez, Vanina Tonzo, Carolina Simon Guerrero, Jesus Lozano-Fernandez, Gemma I Martinez-Redondo, Pau Balart-Garcia, Leandro Aristide, Klara Eleftheriadi, Carlos Vargas-Chavez | <p style="text-align: justify;">With the advent of high throughput sequencing, the amount of genomic data available for animals (Metazoa) species has bloomed over the last decade, especially from transcriptomes due to lower sequencing costs and ea... |  | Bioinformatics, Evolutionary genomics, Functional genomics | Samuel Abalde | 2022-07-20 07:30:39 | View | |

24 Jan 2024

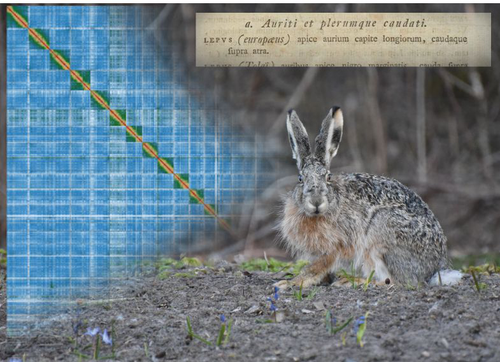

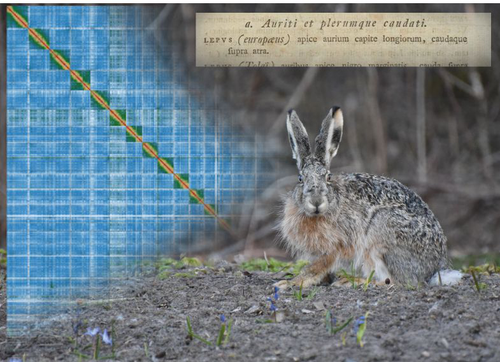

High quality genome assembly of the brown hare (Lepus europaeus) with chromosome-level scaffoldingCraig Michell, Joanna Collins, Pia K. Laine, Zsofia Fekete, Riikka Tapanainen, Jonathan M. D. Wood, Steffi Goffart, Jaakko L. O. Pohjoismaki https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.29.555262A high quality reference genome of the brown hareRecommended by Ed Hollox based on reviews by Merce Montoliu-Nerin and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Merce Montoliu-Nerin and 1 anonymous reviewer

The brown hare, or European hare, Lupus europaeus, is a widespread mammal whose natural range spans western Eurasia. At the northern limit of its range, it hybridises with the mountain hare (L. timidis), and humans have introduced it into other continents. It represents a particularly interesting mammal to study for its population genetics, extensive hybridisation zones, and as an invasive species. This study (Michell et al. 2024) has generated a high-quality assembly of a genome from a brown hare from Finland using long PacBio HiFi sequencing reads and Hi-C scaffolding. The contig N50 of this new genome is 43 Mb, and completeness, assessed using BUSCO, is 96.1%. The assembly comprises 23 autosomes, and an X chromosome and Y chromosome, with many chromosomes including telomeric repeats, indicating the high level of completeness of this assembly. While the genome of the mountain hare has previously been assembled, its assembly was based on a short-read shotgun assembly, with the rabbit as a reference genome. The new high-quality brown hare genome assembly allows a direct comparison with the rabbit genome assembly. For example, the assembly addresses the karyotype difference between the hare (n=24) and the rabbit (n=22). Chromosomes 12 and 17 of the hare are equivalent to chromosome 1 of the rabbit, and chromosomes 13 and 16 of the hare are equivalent to chromosome 2 of the rabbit. The new assembly also provides a hare Y-chromosome, as the previous mountain hare genome was from a female. This new genome assembly provides an important foundation for population genetics and evolutionary studies of lagomorphs. References Michell, C., Collins, J., Laine, P. K., Fekete, Z., Tapanainen, R., Wood, J. M. D., Goffart, S., Pohjoismäki, J. L. O. (2024). High quality genome assembly of the brown hare (Lepus europaeus) with chromosome-level scaffolding. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.29.555262 | High quality genome assembly of the brown hare (*Lepus europaeus*) with chromosome-level scaffolding | Craig Michell, Joanna Collins, Pia K. Laine, Zsofia Fekete, Riikka Tapanainen, Jonathan M. D. Wood, Steffi Goffart, Jaakko L. O. Pohjoismaki | <p style="text-align: justify;">We present here a high-quality genome assembly of the brown hare (Lepus europaeus Pallas), based on a fibroblast cell line of a male specimen from Liperi, Eastern Finland. This brown hare genome represents the first... |  | ERGA Pilot, Vertebrates | Ed Hollox | 2023-10-16 20:46:39 | View | |

18 Jul 2022

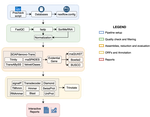

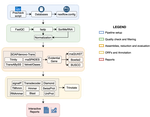

CulebrONT: a streamlined long reads multi-assembler pipeline for prokaryotic and eukaryotic genomesJulie Orjuela, Aurore Comte, Sébastien Ravel, Florian Charriat, Tram Vi, Francois Sabot, Sébastien Cunnac https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.19.452922A flexible and reproducible pipeline for long-read assembly and evaluationRecommended by Raúl Castanera based on reviews by Benjamin Istace and Valentine MurigneuxThird-generation sequencing has revolutionised de novo genome assembly. Thanks to this technology, genome reference sequences have evolved from fragmented drafts to gapless, telomere-to-telomere genome assemblies. Long reads produced by Oxford Nanopore and PacBio technologies can span structural variants and resolve complex repetitive regions such as centromeres, unlocking previously inaccessible genomic information. Nowadays, many research groups can afford to sequence the genome of their working model using long reads. Nevertheless, genome assembly poses a significant computational challenge. Read length, quality, coverage and genomic features such as repeat content can affect assembly contiguity, accuracy, and completeness in almost unpredictable ways. Consequently, there is no best universal software or protocol for this task. Producing a high-quality assembly requires chaining several tools into pipelines and performing extensive comparisons between the assemblies obtained by different tool combinations to decide which one is the best. This task can be extremely challenging, as the number of tools available rises very rapidly, and thorough benchmarks cannot be updated and published at such a fast pace. In their paper, Orjuela and collaborators present CulebrONT [1], a universal pipeline that greatly contributes to overcoming these challenges and facilitates long-read genome assembly for all taxonomic groups. CulebrONT incorporates six commonly used assemblers and allows to perform assembly, circularization (if needed), polishing, and evaluation in a simple framework. One important aspect of CulebrONT is its modularity, which allows the activation or deactivation of specific tools, giving great flexibility to the user. Nevertheless, possibly the best feature of CulebrONT is the opportunity to benchmark the selected tool combinations based on the excellent report generated by the pipeline. This HTML report aggregates the output of several tools for quality evaluation of the assemblies (e.g. BUSCO [2] or QUAST [3]) generated by the different assemblers, in addition to the running time and configuration parameters. Such information is of great help to identify the best-suited pipeline, as exemplified by the authors using four datasets of different taxonomic origins. Finally, CulebrONT can handle multiple samples in parallel, which makes it a good solution for laboratories looking for multiple assemblies on a large scale. References 1. Orjuela J, Comte A, Ravel S, Charriat F, Vi T, Sabot F, Cunnac S (2022) CulebrONT: a streamlined long reads multi-assembler pipeline for prokaryotic and eukaryotic genomes. bioRxiv, 2021.07.19.452922, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.19.452922 2. Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM (2015) BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics, 31, 3210–3212. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351 3. Gurevich A, Saveliev V, Vyahhi N, Tesler G (2013) QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics, 29, 1072–1075. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086 | CulebrONT: a streamlined long reads multi-assembler pipeline for prokaryotic and eukaryotic genomes | Julie Orjuela, Aurore Comte, Sébastien Ravel, Florian Charriat, Tram Vi, Francois Sabot, Sébastien Cunnac | <p style="text-align: justify;">Using long reads provides higher contiguity and better genome assemblies. However, producing such high quality sequences from raw reads requires to chain a growing set of tools, and determining the best workflow is ... |  | Bioinformatics | Raúl Castanera | Valentine Murigneux | 2022-02-22 16:21:25 | View |

19 Jul 2021

TransPi - a comprehensive TRanscriptome ANalysiS PIpeline for de novo transcriptome assemblyRamon E Rivera-Vicens, Catalina Garcia-Escudero, Nicola Conci, Michael Eitel, Gert Wörheide https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.18.431773TransPI: A balancing act between transcriptome assemblersRecommended by Oleg Simakov based on reviews by Gustavo Sanchez and Juan Daniel Montenegro CabreraEver since the introduction of the first widely usable assemblers for transcriptomic reads (Huang and Madan 1999; Schulz et al. 2012; Simpson et al. 2009; Trapnell et al. 2010, and many more), it has been a technical challenge to compare different methods and to choose the “right” or “best” assembly. It took years until the first widely accepted set of benchmarks beyond raw statistical evaluation became available (e.g., Parra, Bradnam, and Korf 2007; Simão et al. 2015). However, an approach to find the right balance between the number of transcripts or isoforms vs. evolutionary completeness measures has been lacking. This has been particularly pronounced in the field of non-model organisms (i.e., wild species that lack a genomic reference). Often, studies in this area employed only one set of assembly tools (the most often used to this day being Trinity, Haas et al. 2013; Grabherr et al. 2011). While it was relatively straightforward to obtain an initial assembly, its validation, annotation, as well its application to the particular purpose that the study was designed for (phylogenetics, differential gene expression, etc) lacked a clear workflow. This led to many studies using a custom set of tools with ensuing various degrees of reproducibility. TransPi (Rivera-Vicéns et al. 2021) fills this gap by first employing a meta approach using several available transcriptome assemblers and algorithms to produce a combined and reduced transcriptome assembly, then validating and annotating the resulting transcriptome. Notably, TransPI performs an extensive analysis/detection of chimeric transcripts, the results of which show that this new tool often produces fewer misassemblies compared to Trinity. TransPI not only generates a final report that includes the most important plots (in clickable/zoomable format) but also stores all relevant intermediate files, allowing advanced users to take a deeper look and/or experiment with different settings. As running TransPi is largely automated (including its installation via several popular package managers), it is very user-friendly and is likely to become the new "gold standard" for transcriptome analyses, especially of non-model organisms. References Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, Amit I, Adiconis X, Fan L, Raychowdhury R, Zeng Q, Chen Z, Mauceli E, Hacohen N, Gnirke A, Rhind N, di Palma F, Birren BW, Nusbaum C, Lindblad-Toh K, Friedman N, Regev A (2011) Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nature Biotechnology, 29, 644–652. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.1883 Haas BJ, Papanicolaou A, Yassour M, Grabherr M, Blood PD, Bowden J, Couger MB, Eccles D, Li B, Lieber M, MacManes MD, Ott M, Orvis J, Pochet N, Strozzi F, Weeks N, Westerman R, William T, Dewey CN, Henschel R, LeDuc RD, Friedman N, Regev A (2013) De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nature Protocols, 8, 1494–1512. https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2013.084 Huang X, Madan A (1999) CAP3: A DNA Sequence Assembly Program. Genome Research, 9, 868–877. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.9.9.868 Parra G, Bradnam K, Korf I (2007) CEGMA: a pipeline to accurately annotate core genes in eukaryotic genomes. Bioinformatics, 23, 1061–1067. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btm071 Rivera-Vicéns RE, Garcia-Escudero CA, Conci N, Eitel M, Wörheide G (2021) TransPi – a comprehensive TRanscriptome ANalysiS PIpeline for de novo transcriptome assembly. bioRxiv, 2021.02.18.431773, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.18.431773 Schulz MH, Zerbino DR, Vingron M, Birney E (2012) Oases: robust de novo RNA-seq assembly across the dynamic range of expression levels. Bioinformatics, 28, 1086–1092. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bts094 Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM (2015) BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics, 31, 3210–3212. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351 Simpson JT, Wong K, Jackman SD, Schein JE, Jones SJM, Birol İ (2009) ABySS: A parallel assembler for short read sequence data. Genome Research, 19, 1117–1123. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.089532.108 Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, Salzberg SL, Wold BJ, Pachter L (2010) Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nature Biotechnology, 28, 511–515. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.1621 | TransPi - a comprehensive TRanscriptome ANalysiS PIpeline for de novo transcriptome assembly | Ramon E Rivera-Vicens, Catalina Garcia-Escudero, Nicola Conci, Michael Eitel, Gert Wörheide | <p style="text-align: justify;">The use of RNA-Seq data and the generation of de novo transcriptome assemblies have been pivotal for studies in ecology and evolution. This is distinctly true for non-model organisms, where no genome information is ... |  | Bioinformatics, Evolutionary genomics | Oleg Simakov | 2021-02-18 20:56:08 | View | |

07 Aug 2023

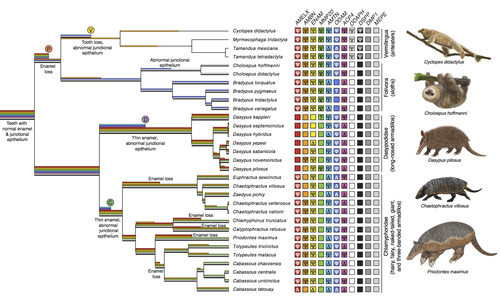

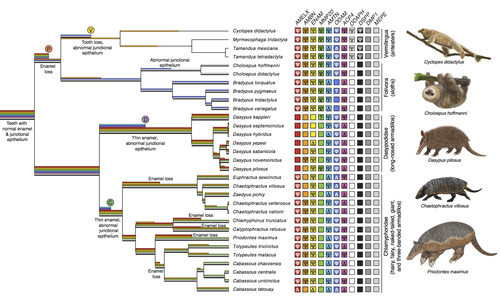

Genomic data suggest parallel dental vestigialization within the xenarthran radiationChristopher A Emerling, Gillian C Gibb, Marie-Ka Tilak, Jonathan J Hughes, Melanie Kuch, Ana T Duggan, Hendrik N Poinar, Michael W Nachman, Frederic Delsuc https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.09.519446What does dental gene decay tell us about the regressive evolution of teeth in South American mammals?Recommended by Didier Casane based on reviews by Juan C. Opazo, Régis Debruyne and Nicolas PolletA group of mammals, Xenathra, evolved and diversified in South America during its long period of isolation in the early to mid Cenozoic era. More recently, as a result of the Great Faunal Interchange between South America and North America, many xenarthran species went extinct. The thirty-one extant species belong to three groups: armadillos, sloths and anteaters. They share dental degeneration. However, the level of degeneration is variable. Anteaters entirely lack teeth, sloths have intermediately regressed teeth and most armadillos have a toothless premaxilla, as well as peg-like, single-rooted teeth that lack enamel in adult animals (Vizcaíno 2009). This diversity raises a number of questions about the evolution of dentition in these mammals. Unfortunately, the fossil record is too poor to provide refined information on the different stages of regressive evolution in these clades. In such cases, the identification of loss-of-function mutations and/or relaxed selection in genes related to a character regression can be very informative (Emerling and Springer 2014; Meredith et al. 2014; Policarpo et al. 2021). Indeed, shared and unique pseudogenes/relaxed selection can tell us to what extent regression has occurred in common ancestors and whether some changes are lineage-specific. In addition, the distribution of pseudogenes/relaxed selection on the branches of a phylogenetic tree is related to the evolutionary processes involved. A much higher density of pseudogenes in the most internal branches indicates that degeneration took place early and over a short period of time, consistent with selection against the presence of the morphological character with which they are associated, while pseudogenes distributed evenly in many internal and external branches suggest a more gradual process over many millions of years, in line with relaxed selection and fixation of loss-of-function mutations by genetic drift. In this paper (Emerling et al. 2023), the authors examined the dynamics of decay of 11 dental genes that may parallel teeth regression. The analyses of the data reported in this paper clearly point to xenarthran teeth having repeatedly regressed in parallel in the three clades. In fact, no loss-of-function mutation is shared by all species examined. However, more genes should be studied to confirm the hypothesis that the common ancestor of extant xenarthrans had normal dentition. There are distinct patterns of gene loss in different lineages that are associated with the variation in dentition observed across the clades. These patterns of gene loss suggest that regressive evolution took place both gradually and in relatively rapid, discrete phases during the diversification of xenarthrans. This study underscores the utility of using pseudogenes to reconstruct evolutionary history of morphological characters when fossils are sparse. References Emerling CA, Gibb GC, Tilak M-K, Hughes JJ, Kuch M, Duggan AT, Poinar HN, Nachman MW, Delsuc F. 2023. Genomic data suggest parallel dental vestigialization within the xenarthran radiation. bioRxiv, 2022.12.09.519446, ver 2, peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.09.519446 Emerling CA, Springer MS. 2014. Eyes underground: Regression of visual protein networks in subterranean mammals. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 78: 260-270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2014.05.016 Meredith RW, Zhang G, Gilbert MTP, Jarvis ED, Springer MS. 2014. Evidence for a single loss of mineralized teeth in the common avian ancestor. Science 346: 1254390. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1254390 Policarpo M, Fumey J, Lafargeas P, Naquin D, Thermes C, Naville M, Dechaud C, Volff J-N, Cabau C, Klopp C, et al. 2021. Contrasting gene decay in subterranean vertebrates: insights from cavefishes and fossorial mammals. Molecular Biology and Evolution 38: 589-605. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msaa249 Vizcaíno SF. 2009. The teeth of the “toothless”: novelties and key innovations in the evolution of xenarthrans (Mammalia, Xenarthra). Paleobiology 35: 343-366. https://doi.org/10.1666/0094-8373-35.3.343 | Genomic data suggest parallel dental vestigialization within the xenarthran radiation | Christopher A Emerling, Gillian C Gibb, Marie-Ka Tilak, Jonathan J Hughes, Melanie Kuch, Ana T Duggan, Hendrik N Poinar, Michael W Nachman, Frederic Delsuc | <p style="text-align: justify;">The recent influx of genomic data has provided greater insights into the molecular basis for regressive evolution, or vestigialization, through gene loss and pseudogenization. As such, the analysis of gene degradati... |  | Evolutionary genomics, Vertebrates | Didier Casane | 2022-12-12 16:01:57 | View | |

05 May 2021

A primer and discussion on DNA-based microbiome data and related bioinformatics analysesGavin M. Douglas and Morgan G. I. Langille https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/3dybgA hitchhiker’s guide to DNA-based microbiome analysisRecommended by Danny Ionescu based on reviews by Nicolas Pollet, Rafael Cuadrat and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Nicolas Pollet, Rafael Cuadrat and 1 anonymous reviewer

In the last two decades, microbial research in its different fields has been increasingly focusing on microbiome studies. These are defined as studies of complete assemblages of microorganisms in given environments and have been benefiting from increases in sequencing length, quality, and yield, coupled with ever-dropping prices per sequenced nucleotide. Alongside localized microbiome studies, several global collaborative efforts have emerged, including the Human Microbiome Project [1], the Earth Microbiome Project [2], the Extreme Microbiome Project, and MetaSUB [3]. Coupled with the development of sequencing technologies and the ever-increasing amount of data output, multiple standalone or online bioinformatic tools have been designed to analyze these data. Often these tools have been focusing on either of two main tasks: 1) Community analysis, providing information on the organisms present in the microbiome, or 2) Functionality, in the case of shotgun metagenomic data, providing information on the metabolic potential of the microbiome. Bridging between the two types of data, often extracted from the same dataset, is typically a daunting task that has been addressed by a handful of tools only. The extent of tools and approaches to analyze microbiome data is great and may be overwhelming to researchers new to microbiome or bioinformatic studies. In their paper “A primer and discussion on DNA-based microbiome data and related bioinformatics analyses”, Douglas and Langille [4] guide us through the different sequencing approaches useful for microbiome studies. alongside their advantages and caveats and a selection of tools to analyze these data, coupled with examples from their own field of research. Standing out in their primer-style review is the emphasis on the coupling between taxonomic/phylogenetic identification of the organisms and their functionality. This type of analysis, though highly important to understand the role of different microorganisms in an environment as well as to identify potential functional redundancy, is often not conducted. For this, the authors identify two approaches. The first, using shotgun metagenomics, has higher chances of attributing a function to the correct taxon. The second, using amplicon sequencing of marker genes, allows for a deeper coverage of the microbiome at a lower cost, and extrapolates the amplicon data to close relatives with a sequenced genome. As clearly stated, this approach makes the leap between taxonomy and functionality and has been shown to be erroneous in cases where the core genome of the bacterial genus or family does not encompass the functional diversity of the different included species. This practice was already common before the genomic era, but its accuracy is improving thanks to the increasing availability of sequenced reference genomes from cultures, environmentally picked single cells or metagenome-assembled genome. In addition to their description of standalone tools useful for linking taxonomy and functionality, one should mention the existence of online tools that may appeal to researchers who do not have access to adequate bioinformatics infrastructure. Among these are the Integrated Microbial Genomes and Microbiomes (IMG) from the Joint Genome Institute [5], KBase [6] and MG-RAST [7]. A second important point arising from this review is the need for standardization in microbiome data analyses and the complexity of achieving this. As Douglas and Langille [4] state, this has been previously addressed, highlighting the variability in results obtained with different tools. It is often the case that papers describing new bioinformatic tools display their superiority relative to existing alternatives, potentially misleading newcomers to the field that the newest tool is the best and only one to be used. This is often not the case, and while benchmarking against well-defined datasets serves as a powerful testing tool, “real-life” samples are often not comparable. Thus, as done here, future primer-like reviews should highlight possible cross-field caveats, encouraging researchers to employ and test several approaches and validate their results whenever possible. In summary, Douglas and Langille [4] offer both the novice and experienced researcher a detailed guide along the paths of microbiome data analysis, accompanied by informative background information, suggested tools with which analyses can be started, and an insightful view on where the field should be heading. References [1] Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Hamady M, Fraser-Liggett CM, Knight R, Gordon JI (2007) The Human Microbiome Project. Nature, 449, 804–810. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06244 [2] Gilbert JA, Jansson JK, Knight R (2014) The Earth Microbiome project: successes and aspirations. BMC Biology, 12, 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-014-0069-1 [3] Mason C, Afshinnekoo E, Ahsannudin S, Ghedin E, Read T, Fraser C, Dudley J, Hernandez M, Bowler C, Stolovitzky G, Chernonetz A, Gray A, Darling A, Burke C, Łabaj PP, Graf A, Noushmehr H, Moraes s., Dias-Neto E, Ugalde J, Guo Y, Zhou Y, Xie Z, Zheng D, Zhou H, Shi L, Zhu S, Tang A, Ivanković T, Siam R, Rascovan N, Richard H, Lafontaine I, Baron C, Nedunuri N, Prithiviraj B, Hyat S, Mehr S, Banihashemi K, Segata N, Suzuki H, Alpuche Aranda CM, Martinez J, Christopher Dada A, Osuolale O, Oguntoyinbo F, Dybwad M, Oliveira M, Fernandes A, Oliveira M, Fernandes A, Chatziefthimiou AD, Chaker S, Alexeev D, Chuvelev D, Kurilshikov A, Schuster S, Siwo GH, Jang S, Seo SC, Hwang SH, Ossowski S, Bezdan D, Udekwu K, Udekwu K, Lungjdahl PO, Nikolayeva O, Sezerman U, Kelly F, Metrustry S, Elhaik E, Gonnet G, Schriml L, Mongodin E, Huttenhower C, Gilbert J, Hernandez M, Vayndorf E, Blaser M, Schadt E, Eisen J, Beitel C, Hirschberg D, Schriml L, Mongodin E, The MetaSUB International Consortium (2016) The Metagenomics and Metadesign of the Subways and Urban Biomes (MetaSUB) International Consortium inaugural meeting report. Microbiome, 4, 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-016-0168-z [4] Douglas GM, Langille MGI (2021) A primer and discussion on DNA-based microbiome data and related bioinformatics analyses. OSF Preprints, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Genomics. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/3dybg [5] Chen I-MA, Markowitz VM, Chu K, Palaniappan K, Szeto E, Pillay M, Ratner A, Huang J, Andersen E, Huntemann M, Varghese N, Hadjithomas M, Tennessen K, Nielsen T, Ivanova NN, Kyrpides NC (2017) IMG/M: integrated genome and metagenome comparative data analysis system. Nucleic Acids Research, 45, D507–D516. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw929 [6] Arkin AP, Cottingham RW, Henry CS, Harris NL, Stevens RL, Maslov S, Dehal P, Ware D, Perez F, Canon S, Sneddon MW, Henderson ML, Riehl WJ, Murphy-Olson D, Chan SY, Kamimura RT, Kumari S, Drake MM, Brettin TS, Glass EM, Chivian D, Gunter D, Weston DJ, Allen BH, Baumohl J, Best AA, Bowen B, Brenner SE, Bun CC, Chandonia J-M, Chia J-M, Colasanti R, Conrad N, Davis JJ, Davison BH, DeJongh M, Devoid S, Dietrich E, Dubchak I, Edirisinghe JN, Fang G, Faria JP, Frybarger PM, Gerlach W, Gerstein M, Greiner A, Gurtowski J, Haun HL, He F, Jain R, Joachimiak MP, Keegan KP, Kondo S, Kumar V, Land ML, Meyer F, Mills M, Novichkov PS, Oh T, Olsen GJ, Olson R, Parrello B, Pasternak S, Pearson E, Poon SS, Price GA, Ramakrishnan S, Ranjan P, Ronald PC, Schatz MC, Seaver SMD, Shukla M, Sutormin RA, Syed MH, Thomason J, Tintle NL, Wang D, Xia F, Yoo H, Yoo S, Yu D (2018) KBase: The United States Department of Energy Systems Biology Knowledgebase. Nature Biotechnology, 36, 566–569. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.4163 [7] Wilke A, Bischof J, Gerlach W, Glass E, Harrison T, Keegan KP, Paczian T, Trimble WL, Bagchi S, Grama A, Chaterji S, Meyer F (2016) The MG-RAST metagenomics database and portal in 2015. Nucleic Acids Research, 44, D590–D594. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv1322 | A primer and discussion on DNA-based microbiome data and related bioinformatics analyses | Gavin M. Douglas and Morgan G. I. Langille | <p style="text-align: justify;">The past decade has seen an eruption of interest in profiling microbiomes through DNA sequencing. The resulting investigations have revealed myriad insights and attracted an influx of researchers to the research are... |  | Bioinformatics, Metagenomics | Danny Ionescu | 2021-02-17 00:26:46 | View | |

15 Dec 2022

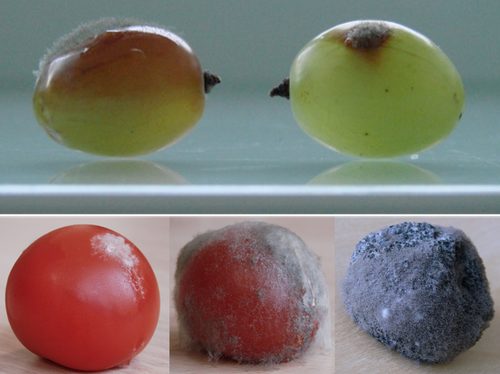

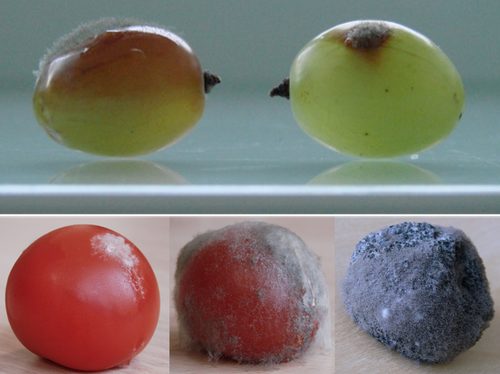

Botrytis cinerea strains infecting grapevine and tomato display contrasted repertoires of accessory chromosomes, transposons and small RNAsAdeline Simon, Alex Mercier, Pierre Gladieux, Benoit Poinssot, Anne-Sophie Walker, Muriel Viaud https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.07.483234Exploring genomic determinants of host specialization in Botrytis cinereaRecommended by Sebastien Duplessis based on reviews by Cecile Lorrain and Thorsten LangnerThe genomics era has pushed forward our understanding of fungal biology. Much progress has been made in unraveling new gene functions and pathways, as well as the evolution or adaptation of fungi to their hosts or environments through population studies (Hartmann et al. 2019; Gladieux et al. 2018). Closing gaps more systematically in draft genomes using the most recent long-read technologies now seems the new standard, even with fungal species presenting complex genome structures (e.g. large and highly repetitive dikaryotic genomes; Duan et al. 2022). Understanding the genomic dynamics underlying host specialization in phytopathogenic fungi is of utmost importance as it may open new avenues to combat diseases. A strong host specialization is commonly observed for biotrophic and hemi-biotrophic fungal species or for necrotrophic fungi with a narrow host range, whereas necrotrophic fungi with broad host range are considered generalists (Liang and Rollins, 2018; Newman and Derbyshire, 2020). However, some degrees of specialization towards given hosts have been reported in generalist fungi and the underlying mechanisms remain to be determined. Botrytis cinerea is a polyphagous necrotrophic phytopathogen with a particularly wide host range and it is notably responsible for grey mould disease on many fruits, such as tomato and grapevine. Because of its importance as a plant pathogen, its relatively small genome size and its taxonomical position, it has been targeted for early genome sequencing and a first reference genome was provided in 2011 (Amselem et al. 2011). Other genomes were subsequently sequenced for other strains, and most importantly a gapless assembled version of the initial reference genome B05.10 was provided to the community (van Kan et al. 2017). This genomic resource has supported advances in various aspects of the biology of B. cinerea such as the production of specialized metabolites, which plays an important role in host-plant colonization, or more recently in the production of small RNAs which interfere with the host immune system, representing a new class of non-proteinaceous virulence effectors (Dalmais et al. 2011; Weiberg et al. 2013). In the present study, Simon et al. (2022) use PacBio long-read sequencing for Sl3 and Vv3 strains, which represent genetic clusters in B. cinerea populations found on tomato and grapevine. The authors combined these complete and high-quality genome assemblies with the B05.10 reference genome and population sequencing data to perform a comparative genomic analysis of specialization towards the two host plants. Transposable elements generate genomic diversity due to their mobile and repetitive nature and they are of utmost importance in the evolution of fungi as they deeply reshape the genomic landscape (Lorrain et al. 2021). Accessory chromosomes are also known drivers of adaptation in fungi (Möller and Stukenbrock, 2017). Here, the authors identify several genomic features such as the presence of different sets of accessory chromosomes, the presence of differentiated repertoires of transposable elements, as well as related small RNAs in the tomato and grapevine populations, all of which may be involved in host specialization. Whereas core chromosomes are highly syntenic between strains, an accessory chromosome validated by pulse-field electrophoresis is specific of the strains isolated from grapevine. Particularly, they show that two particular retrotransposons are discriminant between the strains and that they allow the production of small RNAs that may act as effectors. The discriminant accessory chromosome of the Vv3 strain harbors one of the unraveled retrotransposons as well as new genes of yet unidentified function. I recommend this article because it perfectly illustrates how efforts put into generating reference genomic sequences of higher quality can lead to new discoveries and allow to build strong hypotheses about biology and evolution in fungi. Also, the study combines an up-to-date genomics approach with a classical methodology such as pulse-field electrophoresis to validate the presence of accessory chromosomes. A major input of this investigation of the genomic determinants of B. cinerea is that it provides solid hints for further analysis of host-specialization at the population level in a broad-scale phytopathogenic fungus. References Amselem J, Cuomo CA, Kan JAL van, Viaud M, Benito EP, Couloux A, Coutinho PM, Vries RP de, Dyer PS, Fillinger S, Fournier E, Gout L, Hahn M, Kohn L, Lapalu N, Plummer KM, Pradier J-M, Quévillon E, Sharon A, Simon A, Have A ten, Tudzynski B, Tudzynski P, Wincker P, Andrew M, Anthouard V, Beever RE, Beffa R, Benoit I, Bouzid O, Brault B, Chen Z, Choquer M, Collémare J, Cotton P, Danchin EG, Silva CD, Gautier A, Giraud C, Giraud T, Gonzalez C, Grossetete S, Güldener U, Henrissat B, Howlett BJ, Kodira C, Kretschmer M, Lappartient A, Leroch M, Levis C, Mauceli E, Neuvéglise C, Oeser B, Pearson M, Poulain J, Poussereau N, Quesneville H, Rascle C, Schumacher J, Ségurens B, Sexton A, Silva E, Sirven C, Soanes DM, Talbot NJ, Templeton M, Yandava C, Yarden O, Zeng Q, Rollins JA, Lebrun M-H, Dickman M (2011) Genomic Analysis of the Necrotrophic Fungal Pathogens Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and Botrytis cinerea. PLOS Genetics, 7, e1002230. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002230 Dalmais B, Schumacher J, Moraga J, Le Pêcheur P, Tudzynski B, Collado IG, Viaud M (2011) The Botrytis cinerea phytotoxin botcinic acid requires two polyketide synthases for production and has a redundant role in virulence with botrydial. Molecular Plant Pathology, 12, 564–579. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1364-3703.2010.00692.x Duan H, Jones AW, Hewitt T, Mackenzie A, Hu Y, Sharp A, Lewis D, Mago R, Upadhyaya NM, Rathjen JP, Stone EA, Schwessinger B, Figueroa M, Dodds PN, Periyannan S, Sperschneider J (2022) Physical separation of haplotypes in dikaryons allows benchmarking of phasing accuracy in Nanopore and HiFi assemblies with Hi-C data. Genome Biology, 23, 84. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-022-02658-2 Gladieux P, Condon B, Ravel S, Soanes D, Maciel JLN, Nhani A, Chen L, Terauchi R, Lebrun M-H, Tharreau D, Mitchell T, Pedley KF, Valent B, Talbot NJ, Farman M, Fournier E (2018) Gene Flow between Divergent Cereal- and Grass-Specific Lineages of the Rice Blast Fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. mBio, 9, e01219-17. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.01219-17 Hartmann FE, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, Carpentier F, Gladieux P, Cornille A, Hood ME, Giraud T (2019) Understanding Adaptation, Coevolution, Host Specialization, and Mating System in Castrating Anther-Smut Fungi by Combining Population and Comparative Genomics. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 57, 431–457. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-phyto-082718-095947 Liang X, Rollins JA (2018) Mechanisms of Broad Host Range Necrotrophic Pathogenesis in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Phytopathology®, 108, 1128–1140. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-06-18-0197-RVW Lorrain C, Oggenfuss U, Croll D, Duplessis S, Stukenbrock E (2021) Transposable Elements in Fungi: Coevolution With the Host Genome Shapes, Genome Architecture, Plasticity and Adaptation. In: Encyclopedia of Mycology (eds Zaragoza Ó, Casadevall A), pp. 142–155. Elsevier, Oxford. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-819990-9.00042-1 Möller M, Stukenbrock EH (2017) Evolution and genome architecture in fungal plant pathogens. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 15, 756–771. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2017.76 Newman TE, Derbyshire MC (2020) The Evolutionary and Molecular Features of Broad Host-Range Necrotrophy in Plant Pathogenic Fungi. Frontiers in Plant Science, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.591733 Simon A, Mercier A, Gladieux P, Poinssot B, Walker A-S, Viaud M (2022) Botrytis cinerea strains infecting grapevine and tomato display contrasted repertoires of accessory chromosomes, transposons and small RNAs. bioRxiv, 2022.03.07.483234, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.07.483234 Van Kan JAL, Stassen JHM, Mosbach A, Van Der Lee TAJ, Faino L, Farmer AD, Papasotiriou DG, Zhou S, Seidl MF, Cottam E, Edel D, Hahn M, Schwartz DC, Dietrich RA, Widdison S, Scalliet G (2017) A gapless genome sequence of the fungus Botrytis cinerea. Molecular Plant Pathology, 18, 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/mpp.12384 Weiberg A, Wang M, Lin F-M, Zhao H, Zhang Z, Kaloshian I, Huang H-D, Jin H (2013) Fungal Small RNAs Suppress Plant Immunity by Hijacking Host RNA Interference Pathways. Science, 342, 118–123. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1239705 | Botrytis cinerea strains infecting grapevine and tomato display contrasted repertoires of accessory chromosomes, transposons and small RNAs | Adeline Simon, Alex Mercier, Pierre Gladieux, Benoit Poinssot, Anne-Sophie Walker, Muriel Viaud | <p style="text-align: justify;">The fungus <em>Botrytis cinerea</em> is a polyphagous pathogen that encompasses multiple host-specialized lineages. While several secreted proteins, secondary metabolites and retrotransposons-derived small RNAs have... |  | Fungi, Structural genomics, Viruses and transposable elements | Sebastien Duplessis | Cecile Lorrain, Thorsten Langner | 2022-03-15 11:15:48 | View |