Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * ▲ | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

15 Dec 2022

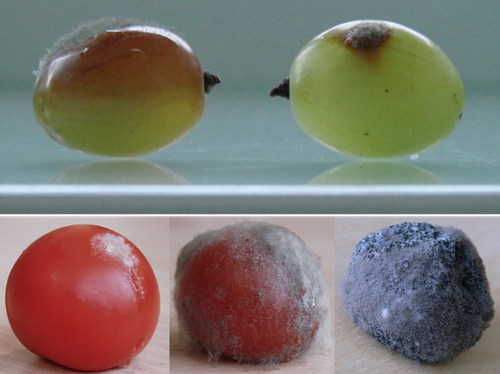

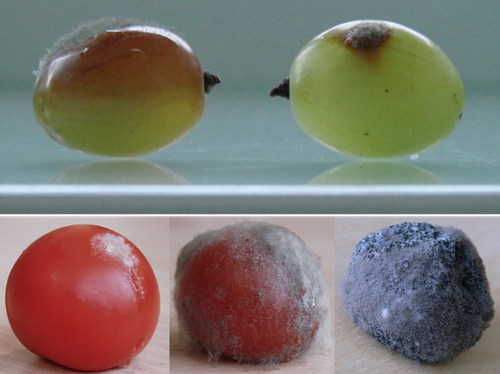

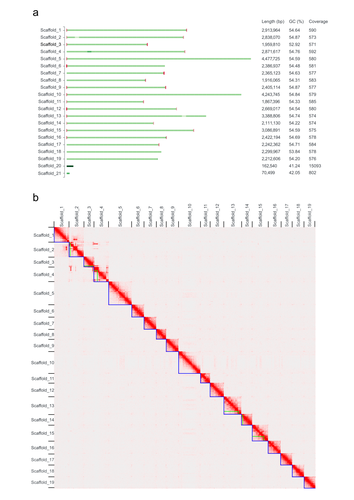

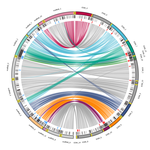

Botrytis cinerea strains infecting grapevine and tomato display contrasted repertoires of accessory chromosomes, transposons and small RNAsAdeline Simon, Alex Mercier, Pierre Gladieux, Benoit Poinssot, Anne-Sophie Walker, Muriel Viaud https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.07.483234Exploring genomic determinants of host specialization in Botrytis cinereaRecommended by Sebastien Duplessis based on reviews by Cecile Lorrain and Thorsten LangnerThe genomics era has pushed forward our understanding of fungal biology. Much progress has been made in unraveling new gene functions and pathways, as well as the evolution or adaptation of fungi to their hosts or environments through population studies (Hartmann et al. 2019; Gladieux et al. 2018). Closing gaps more systematically in draft genomes using the most recent long-read technologies now seems the new standard, even with fungal species presenting complex genome structures (e.g. large and highly repetitive dikaryotic genomes; Duan et al. 2022). Understanding the genomic dynamics underlying host specialization in phytopathogenic fungi is of utmost importance as it may open new avenues to combat diseases. A strong host specialization is commonly observed for biotrophic and hemi-biotrophic fungal species or for necrotrophic fungi with a narrow host range, whereas necrotrophic fungi with broad host range are considered generalists (Liang and Rollins, 2018; Newman and Derbyshire, 2020). However, some degrees of specialization towards given hosts have been reported in generalist fungi and the underlying mechanisms remain to be determined. Botrytis cinerea is a polyphagous necrotrophic phytopathogen with a particularly wide host range and it is notably responsible for grey mould disease on many fruits, such as tomato and grapevine. Because of its importance as a plant pathogen, its relatively small genome size and its taxonomical position, it has been targeted for early genome sequencing and a first reference genome was provided in 2011 (Amselem et al. 2011). Other genomes were subsequently sequenced for other strains, and most importantly a gapless assembled version of the initial reference genome B05.10 was provided to the community (van Kan et al. 2017). This genomic resource has supported advances in various aspects of the biology of B. cinerea such as the production of specialized metabolites, which plays an important role in host-plant colonization, or more recently in the production of small RNAs which interfere with the host immune system, representing a new class of non-proteinaceous virulence effectors (Dalmais et al. 2011; Weiberg et al. 2013). In the present study, Simon et al. (2022) use PacBio long-read sequencing for Sl3 and Vv3 strains, which represent genetic clusters in B. cinerea populations found on tomato and grapevine. The authors combined these complete and high-quality genome assemblies with the B05.10 reference genome and population sequencing data to perform a comparative genomic analysis of specialization towards the two host plants. Transposable elements generate genomic diversity due to their mobile and repetitive nature and they are of utmost importance in the evolution of fungi as they deeply reshape the genomic landscape (Lorrain et al. 2021). Accessory chromosomes are also known drivers of adaptation in fungi (Möller and Stukenbrock, 2017). Here, the authors identify several genomic features such as the presence of different sets of accessory chromosomes, the presence of differentiated repertoires of transposable elements, as well as related small RNAs in the tomato and grapevine populations, all of which may be involved in host specialization. Whereas core chromosomes are highly syntenic between strains, an accessory chromosome validated by pulse-field electrophoresis is specific of the strains isolated from grapevine. Particularly, they show that two particular retrotransposons are discriminant between the strains and that they allow the production of small RNAs that may act as effectors. The discriminant accessory chromosome of the Vv3 strain harbors one of the unraveled retrotransposons as well as new genes of yet unidentified function. I recommend this article because it perfectly illustrates how efforts put into generating reference genomic sequences of higher quality can lead to new discoveries and allow to build strong hypotheses about biology and evolution in fungi. Also, the study combines an up-to-date genomics approach with a classical methodology such as pulse-field electrophoresis to validate the presence of accessory chromosomes. A major input of this investigation of the genomic determinants of B. cinerea is that it provides solid hints for further analysis of host-specialization at the population level in a broad-scale phytopathogenic fungus. References Amselem J, Cuomo CA, Kan JAL van, Viaud M, Benito EP, Couloux A, Coutinho PM, Vries RP de, Dyer PS, Fillinger S, Fournier E, Gout L, Hahn M, Kohn L, Lapalu N, Plummer KM, Pradier J-M, Quévillon E, Sharon A, Simon A, Have A ten, Tudzynski B, Tudzynski P, Wincker P, Andrew M, Anthouard V, Beever RE, Beffa R, Benoit I, Bouzid O, Brault B, Chen Z, Choquer M, Collémare J, Cotton P, Danchin EG, Silva CD, Gautier A, Giraud C, Giraud T, Gonzalez C, Grossetete S, Güldener U, Henrissat B, Howlett BJ, Kodira C, Kretschmer M, Lappartient A, Leroch M, Levis C, Mauceli E, Neuvéglise C, Oeser B, Pearson M, Poulain J, Poussereau N, Quesneville H, Rascle C, Schumacher J, Ségurens B, Sexton A, Silva E, Sirven C, Soanes DM, Talbot NJ, Templeton M, Yandava C, Yarden O, Zeng Q, Rollins JA, Lebrun M-H, Dickman M (2011) Genomic Analysis of the Necrotrophic Fungal Pathogens Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and Botrytis cinerea. PLOS Genetics, 7, e1002230. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002230 Dalmais B, Schumacher J, Moraga J, Le Pêcheur P, Tudzynski B, Collado IG, Viaud M (2011) The Botrytis cinerea phytotoxin botcinic acid requires two polyketide synthases for production and has a redundant role in virulence with botrydial. Molecular Plant Pathology, 12, 564–579. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1364-3703.2010.00692.x Duan H, Jones AW, Hewitt T, Mackenzie A, Hu Y, Sharp A, Lewis D, Mago R, Upadhyaya NM, Rathjen JP, Stone EA, Schwessinger B, Figueroa M, Dodds PN, Periyannan S, Sperschneider J (2022) Physical separation of haplotypes in dikaryons allows benchmarking of phasing accuracy in Nanopore and HiFi assemblies with Hi-C data. Genome Biology, 23, 84. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-022-02658-2 Gladieux P, Condon B, Ravel S, Soanes D, Maciel JLN, Nhani A, Chen L, Terauchi R, Lebrun M-H, Tharreau D, Mitchell T, Pedley KF, Valent B, Talbot NJ, Farman M, Fournier E (2018) Gene Flow between Divergent Cereal- and Grass-Specific Lineages of the Rice Blast Fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. mBio, 9, e01219-17. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.01219-17 Hartmann FE, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, Carpentier F, Gladieux P, Cornille A, Hood ME, Giraud T (2019) Understanding Adaptation, Coevolution, Host Specialization, and Mating System in Castrating Anther-Smut Fungi by Combining Population and Comparative Genomics. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 57, 431–457. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-phyto-082718-095947 Liang X, Rollins JA (2018) Mechanisms of Broad Host Range Necrotrophic Pathogenesis in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Phytopathology®, 108, 1128–1140. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-06-18-0197-RVW Lorrain C, Oggenfuss U, Croll D, Duplessis S, Stukenbrock E (2021) Transposable Elements in Fungi: Coevolution With the Host Genome Shapes, Genome Architecture, Plasticity and Adaptation. In: Encyclopedia of Mycology (eds Zaragoza Ó, Casadevall A), pp. 142–155. Elsevier, Oxford. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-819990-9.00042-1 Möller M, Stukenbrock EH (2017) Evolution and genome architecture in fungal plant pathogens. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 15, 756–771. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2017.76 Newman TE, Derbyshire MC (2020) The Evolutionary and Molecular Features of Broad Host-Range Necrotrophy in Plant Pathogenic Fungi. Frontiers in Plant Science, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.591733 Simon A, Mercier A, Gladieux P, Poinssot B, Walker A-S, Viaud M (2022) Botrytis cinerea strains infecting grapevine and tomato display contrasted repertoires of accessory chromosomes, transposons and small RNAs. bioRxiv, 2022.03.07.483234, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.07.483234 Van Kan JAL, Stassen JHM, Mosbach A, Van Der Lee TAJ, Faino L, Farmer AD, Papasotiriou DG, Zhou S, Seidl MF, Cottam E, Edel D, Hahn M, Schwartz DC, Dietrich RA, Widdison S, Scalliet G (2017) A gapless genome sequence of the fungus Botrytis cinerea. Molecular Plant Pathology, 18, 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/mpp.12384 Weiberg A, Wang M, Lin F-M, Zhao H, Zhang Z, Kaloshian I, Huang H-D, Jin H (2013) Fungal Small RNAs Suppress Plant Immunity by Hijacking Host RNA Interference Pathways. Science, 342, 118–123. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1239705 | Botrytis cinerea strains infecting grapevine and tomato display contrasted repertoires of accessory chromosomes, transposons and small RNAs | Adeline Simon, Alex Mercier, Pierre Gladieux, Benoit Poinssot, Anne-Sophie Walker, Muriel Viaud | <p style="text-align: justify;">The fungus <em>Botrytis cinerea</em> is a polyphagous pathogen that encompasses multiple host-specialized lineages. While several secreted proteins, secondary metabolites and retrotransposons-derived small RNAs have... |  | Fungi, Structural genomics, Viruses and transposable elements | Sebastien Duplessis | Cecile Lorrain, Thorsten Langner | 2022-03-15 11:15:48 | View |

18 Feb 2021

Traces of transposable element in genome dark matter co-opted by flowering gene regulation networksAgnes Baud, Mariene Wan, Danielle Nouaud, Nicolas Francillonne, Dominique Anxolabehere, Hadi Quesneville https://doi.org/10.1101/547877Using small fragments to discover old TE remnants: the Duster approach empowers the TE detectionRecommended by Francois Sabot based on reviews by Josep Casacuberta and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Josep Casacuberta and 1 anonymous reviewer

Transposable elements are the raw material of the dark matter of the genome, the foundation of the next generation of genes and regulation networks". This sentence could be the essence of the paper of Baud et al. (2021). Transposable elements (TEs) are endogenous mobile genetic elements found in almost all genomes, which were discovered in 1948 by Barbara McClintock (awarded in 1983 the only unshared Medicine Nobel Prize so far). TEs are present everywhere, from a single isolated copy for some elements to more than millions for others, such as Alu. They are founders of major gene lineages (HET-A, TART and telomerases, RAG1/RAG2 proteins from mammals immune system; Diwash et al, 2017), and even of retroviruses (Xiong & Eickbush, 1988). However, most TEs appear as selfish elements that replicate, land in a new genomic region, then start to decay and finally disappear in the midst of the genome, turning into genomic ‘dark matter’ (Vitte et al, 2007). The mutations (single point, deletion, recombination, and so on) that occur during this slow death erase some of their most notable features and signature sequences, rendering them completely unrecognizable after a few million years. Numerous TE detection tools have tried to optimize their detection (Goerner-Potvin & Bourque, 2018), but further improvement is definitely challenging. This is what Baud et al. (2021) accomplished in their paper. They used a simple, elegant and efficient k-mer based approach to find small signatures that, when accumulated, allow identifying very old TEs. Using this method, called Duster, they improved the amount of annotated TEs in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana by 20%, pushing the part of this genome occupied by TEs up from 40 to almost 50%. They further observed that these very old Duster-specific TEs (i.e., TEs that are only detected by Duster) are, among other properties, close to genes (much more than recent TEs), not targeted by small RNA pathways, and highly associated with conserved regions across the rosid family. In addition, they are highly associated with flowering or stress response genes, and may be involved through exaptation in the evolution of responses to environmental changes. TEs are not just selfish elements: more and more studies have shown their key role in the evolution of their hosts, and tools such as Duster will help us better understand their impact. References Baud, A., Wan, M., Nouaud, D., Francillonne, N., Anxolabéhère, D. and Quesneville, H. (2021). Traces of transposable elements in genome dark matter co-opted by flowering gene regulation networks. bioRxiv, 547877, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Genomics.doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/547877 | Traces of transposable element in genome dark matter co-opted by flowering gene regulation networks | Agnes Baud, Mariene Wan, Danielle Nouaud, Nicolas Francillonne, Dominique Anxolabehere, Hadi Quesneville | <p>Transposable elements (TEs) are mobile, repetitive DNA sequences that make the largest contribution to genome bulk. They thus contribute to the so-called 'dark matter of the genome', the part of the genome in which nothing is immediately recogn... |  | Bioinformatics, Evolutionary genomics, Functional genomics, Plants, Structural genomics, Viruses and transposable elements | Francois Sabot | Anonymous, Josep Casacuberta | 2020-04-07 17:12:12 | View |

22 May 2023

Genetic bases of resistance to the rice hoja blanca disease deciphered by a QTL approachAlexander Silva, Maria Elker Montoya, Constanza Quintero, Juan Cuasquer, Joe Tohme, Eduardo Graterol, Maribel Cruz, Mathias Lorieux https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.07.515427Scoring symptoms of a plant viral diseaseRecommended by Olivier Panaud based on reviews by Grégoire Aubert and Valérie GeffroyThe paper from Silva et al. (2023) provides new insights into the genetic bases of natural resistance of rice to the Rice Hoja Blanca (RHB) disease, one of its most serious diseases in tropical countries of the American continent and the Caribbean. This disease is caused by the Rice Hoja Blanca Virus, or RHBV, the vector of which is the planthopper insect Tagosodes orizicolus Müir. It is responsible for serious damage to the rice crop (Morales and Jennings 2010). The authors take a Quantitative Trait Loci (QTL) detection approach to find genomic regions statistically associated with the resistant phenotype. To this aim, they use four resistant x susceptible crosses (the susceptible parent being the same in all four crosses) to maximize the chances to find new QTLs. The F2 populations derived from the crosses are genotyped using Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) extracted from whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data of the resistant parents, and the F3 families derived from the F2 individuals are scored for disease symptoms. For this, they use a computer-aided image analysis protocol that they designed so they can estimate the severity of the damages in the plant. They find several new QTLs, some being apparently more associated with disease severity, others with disease incidence. They also find that a previously identified QTL of Oryza sativa ssp. japonica origin is also present in the indica cluster (Romero et al. 2014). Finally, they discuss the candidate genes that could underlie the QTLs and provide a simple model for resistance. It has to be noted that scoring symptoms of a viral disease such as RHB is very challenging. It requires maintaining populations of viruliferous insect vectors, mastering times and conditions for infestation by nymphs, and precise symptom scoring. It also requires the preparation of segregating populations, their genotyping with enough genetic markers, and mastering QTL detection methods. All these aspects are present in this work. In particular, the phenotyping of symptom severity implemented using computer-aided image processing represents an impressive, enormous amount of work. From the genomics side, the fine-scale genotyping is based on the WGS of the parental lines (resistant and susceptible), followed by the application of suitable bioinformatic tools for SNP extraction and primers prediction that can be used on their Fluidigm platform. It also required implementing data correction algorithms to achieve precise genetic maps in the four crosses. The QTL detection itself required careful statistical pre-processing of phenotypic data. The authors then used a combination of several QTL detection methods, including an original meta-QTL method they developed in the software MapDisto. The authors then perform a very complete and convincing analysis of candidate genes, which includes genes already identified for a similar disease (RSV) on chromosome 11 of rice. What remains to elucidate is whether the candidate genes are actually involved or not in the disease resistance process. The team has already started implementing gene knockout strategies to study some of them in more detail. It will be interesting to see whether those genes act against the virus itself, or against the insect vector. Overall the work is of high quality and represents an important advance in the knowledge of disease resistance. In addition, it has many implications for crop breeding, allowing the setup of large-scale, marker-assisted strategies, for new resistant elite varieties of rice. References Morales F and Jennings P (2010) Rice hoja blanca: a complex plant-virus-vector pathosystem. CAB Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1079/PAVSNNR20105043 Romero LE, Lozano I, Garavito A, et al (2014) Major QTLs control resistance to Rice hoja blanca virus and its vector Tagosodes orizicolus. G3 | Genes, Genomes, Genetics 4:133–142. https://doi.org/10.1534/g3.113.009373 Silva A, Montoya ME, Quintero C, Cuasquer J, Tohme J, Graterol E, Cruz M, Lorieux M (2023) Genetic bases of resistance to the rice hoja blanca disease deciphered by a QTL approach. bioRxiv, 2022.11.07.515427, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.07.515427 | Genetic bases of resistance to the rice hoja blanca disease deciphered by a QTL approach | Alexander Silva, Maria Elker Montoya, Constanza Quintero, Juan Cuasquer, Joe Tohme, Eduardo Graterol, Maribel Cruz, Mathias Lorieux | <p style="text-align: justify;">Rice hoja blanca (RHB) is one of the most serious diseases in rice growing areas in tropical Americas. Its causal agent is Rice hoja blanca virus (RHBV), transmitted by the planthopper <em>Tagosodes orizicolus </em>... |  | Functional genomics, Plants | Olivier Panaud | 2022-11-09 09:13:30 | View | |

20 Jul 2021

Genetic mapping of sex and self-incompatibility determinants in the androdioecious plant Phillyrea angustifoliaAmelie Carre, Sophie Gallina, Sylvain Santoni, Philippe Vernet, Cecile Gode, Vincent Castric, Pierre Saumitou-Laprade https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.15.439943Identification of distinct YX-like loci for sex determination and self-incompatibility in an androdioecious shrubRecommended by Tatiana Giraud and Ricardo C. Rodríguez de la Vega based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersA wide variety of systems have evolved to control mating compatibility in sexual organisms. Their genetic determinism and the factors controlling their evolution represent fascinating questions in evolutionary biology and genomics. The plant Phillyrea angustifolia (Oleaeceae family) represents an exciting model organism, as it displays two distinct and rare mating compatibility systems [1]: 1) males and hermaphrodites co-occur in populations of this shrub (a rare system called androdioecy), while the evolution and maintenance of purely hermaphroditic plants or mixtures of females and hermaphrodites (a system called gynodioecy) are easier to explain [2]; 2) a homomorphic diallelic self-incompatibility system acts in hermaphrodites, while such systems are usually multi-allelic, as rare alleles are advantageous, being compatible with all other alleles. Previous analyses of crosses brought some interesting answers to these puzzles, showing that males benefit from the ability to mate with all hermaphrodites regardless of their allele at the self-incompatibility system, and suggesting that both sex and self incompatibility are determined by XY-like genetic systems, i.e. with each a dominant allele; homozygotes for a single allele and heterozygotes therefore co-occur in natural populations at both sex and self-incompatibility loci [3]. Here, Carré et al. used genotyping-by-sequencing to build a genome linkage map of P. angustifolia [4]. The elegant and original use of a probabilistic model of segregating alleles (implemented in the SEX-DETector method) allowed to identify both the sex and self-incompatibility loci [4], while this tool was initially developed for detecting sex-linked genes in species with strictly separated sexes (dioecy) [5]. Carré et al. [4] confirmed that the sex and self-incompatibility loci are located in two distinct linkage groups and correspond to XY-like systems. A comparison with the genome of the closely related Olive tree indicated that their self-incompatibility systems were homologous. Such a XY-like system represents a rare genetic determination mechanism for self-incompatibility and has also been recently found to control mating types in oomycetes [6]. This study [4] paves the way for identifying the genes controlling the sex and self-incompatibility phenotypes and for understanding why and how self-incompatibility is only expressed in hermaphrodites and not in males. It will also be fascinating to study more finely the degree and extent of genomic differentiation at these two loci and to assess whether recombination suppression has extended stepwise away from the sex and self-incompatibility loci, as can be expected under some hypotheses, such as the sheltering of deleterious alleles near permanently heterozygous alleles [7]. Furthermore, the co-occurrence in P. angustifolia of sex and mating types can contribute to our understanding of the factor controlling their evolution [8]. References [1] Saumitou-Laprade P, Vernet P, Vassiliadis C, Hoareau Y, Magny G de, Dommée B, Lepart J (2010) A Self-Incompatibility System Explains High Male Frequencies in an Androdioecious Plant. Science, 327, 1648–1650. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1186687 [2] Pannell JR, Voillemot M (2015) Plant Mating Systems: Female Sterility in the Driver’s Seat. Current Biology, 25, R511–R514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.04.044 [3] Billiard S, Husse L, Lepercq P, Godé C, Bourceaux A, Lepart J, Vernet P, Saumitou-Laprade P (2015) Selfish male-determining element favors the transition from hermaphroditism to androdioecy. Evolution, 69, 683–693. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12613 [4] Carre A, Gallina S, Santoni S, Vernet P, Gode C, Castric V, Saumitou-Laprade P (2021) Genetic mapping of sex and self-incompatibility determinants in the androdioecious plant Phillyrea angustifolia. bioRxiv, 2021.04.15.439943, ver. 7 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.15.439943 [5] Muyle A, Käfer J, Zemp N, Mousset S, Picard F, Marais GA (2016) SEX-DETector: A Probabilistic Approach to Study Sex Chromosomes in Non-Model Organisms. Genome Biology and Evolution, 8, 2530–2543. https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evw172 [6] Dussert Y, Legrand L, Mazet ID, Couture C, Piron M-C, Serre R-F, Bouchez O, Mestre P, Toffolatti SL, Giraud T, Delmotte F (2020) Identification of the First Oomycete Mating-type Locus Sequence in the Grapevine Downy Mildew Pathogen, Plasmopara viticola. Current Biology, 30, 3897-3907.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.07.057 [7] Jay P, Tezenas E, Giraud T (2021) A deleterious mutation-sheltering theory for the evolution of sex chromosomes and supergenes. bioRxiv, 2021.05.17.444504. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.17.444504 [8] Billiard S, López-Villavicencio M, Devier B, Hood ME, Fairhead C, Giraud T (2011) Having sex, yes, but with whom? Inferences from fungi on the evolution of anisogamy and mating types. Biological Reviews, 86, 421–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-185X.2010.00153.x | Genetic mapping of sex and self-incompatibility determinants in the androdioecious plant Phillyrea angustifolia | Amelie Carre, Sophie Gallina, Sylvain Santoni, Philippe Vernet, Cecile Gode, Vincent Castric, Pierre Saumitou-Laprade | <p style="text-align: justify;">The diversity of mating and sexual systems in angiosperms is spectacular, but the factors driving their evolution remain poorly understood. In plants of the Oleaceae family, an unusual self-incompatibility (SI) syst... |  | Evolutionary genomics, Plants | Tatiana Giraud | 2021-05-04 10:37:26 | View | |

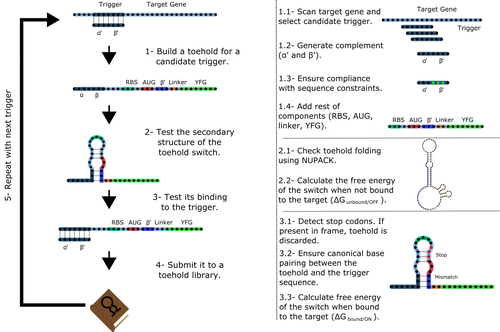

16 Dec 2022

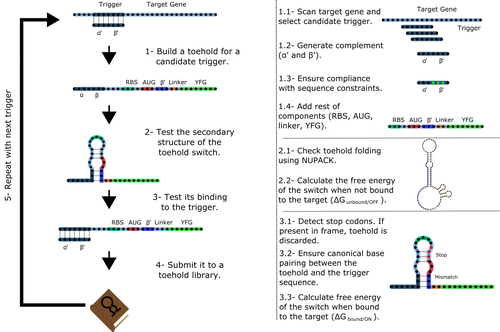

Toeholder: a Software for Automated Design and In Silico Validation of Toehold RiboswitchesAngel F. Cisneros, François D. Rouleau, Carla Bautista, Pascale Lemieux, Nathan Dumont-Leblond https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.09.467922A novel approach for engineering biological systems by interfacing computer science with synthetic biologyRecommended by Sahar Melamed based on reviews by Wim Wranken and 1 anonymous reviewerBiological systems depend on finely tuned interactions of their components. Thus, regulating these components is critical for the system's functionality. In prokaryotic cells, riboswitches are regulatory elements controlling transcription or translation. Riboswitches are RNA molecules that are usually located in the 5′-untranslated region of protein-coding genes. They generate secondary structures leading to the regulation of the expression of the downstream protein-coding gene (Kavita and Breaker, 2022). Riboswitches are very versatile and can bind a wide range of small molecules; in many cases, these are metabolic byproducts from the gene’s enzymatic or signaling pathway. Their versatility and abundance in many species make them attractive for synthetic biological circuits. One class that has been drawing the attention of synthetic biologists is toehold switches (Ekdahl et al., 2022; Green et al., 2014). These are single-stranded RNA molecules harboring the necessary elements for translation initiation of the downstream gene: a ribosome-binding site and a start codon. Conformation change of toehold switches is triggered by an RNA molecule, which enables translation. To exploit the most out of toehold switches, automation of their design would be highly advantageous. Cisneros and colleagues (Cisneros et al., 2022) developed a tool, “Toeholder”, that automates the design of toehold switches and performs in silico tests to select switch candidates for a target gene. Toeholder is an open-source tool that provides a comprehensive and automated workflow for the design of toehold switches. While web tools have been developed for designing toehold switches (To et al., 2018), Toeholder represents an intriguing approach to engineering biological systems by coupling synthetic biology with computational biology. Using molecular dynamics simulations, it identified the positions in the toehold switch where hydrogen bonds fluctuate the most. Identifying these regions holds great potential for modifications when refining the design of the riboswitches. To be effective, toehold switches should provide a strong ON signal and a weak OFF signal in the presence or the absence of a target, respectively. Toeholder nicely ranks the candidate toehold switches based on experimental evidence that correlates with toehold performance (based on good ON/OFF ratios). Riboswitches are highly appealing for a broad range of applications, including pharmaceutical and medical purposes (Blount and Breaker, 2006; Giarimoglou et al., 2022; Tickner and Farzan, 2021), thanks to their adaptability and inexpensiveness. The Toeholder tool developed by Cisneros and colleagues is expected to promote the implementation of toehold switches into these various applications. References Blount KF, Breaker RR (2006) Riboswitches as antibacterial drug targets. Nature Biotechnology, 24, 1558–1564. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt1268 Cisneros AF, Rouleau FD, Bautista C, Lemieux P, Dumont-Leblond N, ULaval 2019 T iGEM (2022) Toeholder: a Software for Automated Design and In Silico Validation of Toehold Riboswitches. bioRxiv, 2021.11.09.467922, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.09.467922 Ekdahl AM, Rojano-Nisimura AM, Contreras LM (2022) Engineering Toehold-Mediated Switches for Native RNA Detection and Regulation in Bacteria. Journal of Molecular Biology, 434, 167689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2022.167689 Giarimoglou N, Kouvela A, Maniatis A, Papakyriakou A, Zhang J, Stamatopoulou V, Stathopoulos C (2022) A Riboswitch-Driven Era of New Antibacterials. Antibiotics, 11, 1243. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11091243 Green AA, Silver PA, Collins JJ, Yin P (2014) Toehold Switches: De-Novo-Designed Regulators of Gene Expression. Cell, 159, 925–939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.002 Kavita K, Breaker RR (2022) Discovering riboswitches: the past and the future. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2022.08.009 Tickner ZJ, Farzan M (2021) Riboswitches for Controlled Expression of Therapeutic Transgenes Delivered by Adeno-Associated Viral Vectors. Pharmaceuticals, 14, 554. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14060554 To AC-Y, Chu DH-T, Wang AR, Li FC-Y, Chiu AW-O, Gao DY, Choi CHJ, Kong S-K, Chan T-F, Chan K-M, Yip KY (2018) A comprehensive web tool for toehold switch design. Bioinformatics, 34, 2862–2864. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty216 | Toeholder: a Software for Automated Design and In Silico Validation of Toehold Riboswitches | Angel F. Cisneros, François D. Rouleau, Carla Bautista, Pascale Lemieux, Nathan Dumont-Leblond | <p>Abstract: Synthetic biology aims to engineer biological circuits, which often involve gene expression. A particularly promising group of regulatory elements are riboswitches because of their versatility with respect to their targets, but e... |  | Bioinformatics | Sahar Melamed | 2022-02-16 14:40:13 | View | |

11 May 2024

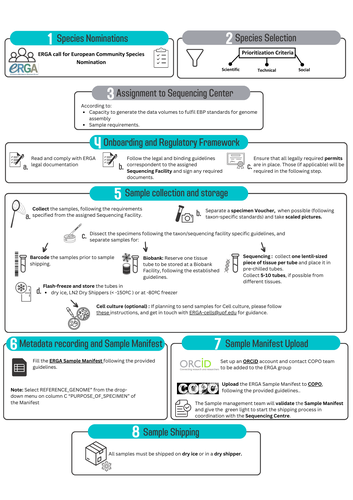

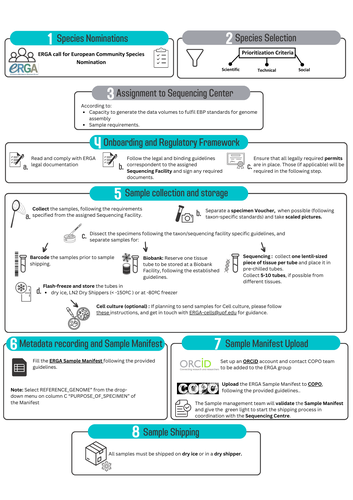

The European Reference Genome Atlas: piloting a decentralised approach to equitable biodiversity genomicsAnn M Mc Cartney, Giulio Formenti, Alice Mouton, Claudio Ciofi, Robert M Waterhouse, Camila J Mazzoni, Diego De Panis, Luisa S Schlude Marins, Henrique G Leitao, Genevieve Diedericks, Joseph Kirangwa, Marco Morselli, Judit Salces, Nuria Escudero, Alessio Iannucci, Chiara Natali, Hannes Svardal, Rosa Fernandez, Tim De Pooter, Geert Joris, Mojca Strazisar, Jo Wood, Katie E Herron, Ole Seehausen, Phillip C Watts, Felix Shaw, Robert P Davey, Alice Minotto, Jose Maria Fernandez Gonzalez, Astrid Bohne... https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.09.25.559365Informed Choices, Cohesive Future: Decisions and Recommendations for ERGARecommended by Jitendra Narayan based on reviews by Justin Ideozu and Eric Crandall based on reviews by Justin Ideozu and Eric Crandall

The European Reference Genome Atlas (ERGA) (Mc Cartney et al, 2024, Mazzoni et al, 2023) demonstrates the collaborative spirit and intellectual abilities of researchers from 33 European countries. This ambitious project, which is part of the Earth BioGenome Project (Lewin et al., 2018) Phase II, has embarked on an unprecedented mission: to decipher the genetic makeup of 150,000 species over a span of four years. At the heart of ERGA is a decentralized pilot infrastructure specifically built to assist the production of high-quality reference genomes. This structure acts as a scaffold for the massive task of genome sequencing, giving the necessary framework to manage the complexity of genomic research. The research paper under consideration offers a comprehensive narrative of ERGA's evolution, outlining both successes and challenges encountered along the road. One of the most significant issues addressed in the manuscript is the equitable distribution of resources and expertise among participating laboratories and countries. In a project of this magnitude, it is critical to leverage the pooled talents and capacities of researchers from across Europe. ERGA's pan-European network promotes communications and collaboration, creating an environment in which knowledge flows freely and barriers are overcome. This adoption of strong coordination and communication tactics will be essential to ERGA's success. Scientific collaboration depends on efficient communication channels because they allow researchers to share resources, collaborate on new initiatives, and exchange ideas. Through a diverse range of gatherings, courses, and virtual discussion boards, ERGA fosters an environment of transparency and cooperation among members, enabling scientists to overcome challenges and make significant discoveries. The importance ERGA places on training and information transfer programmes is a pillar of its strategy. Understanding the importance of capacity development, ERGA invests in providing researchers with the knowledge and abilities necessary for effectively navigating the complicated terrain of genomic research. A wide range of subjects are covered in training programmes (Larivière et al. 2023), from sample preparation and collection to data processing methods and sequencing technology. Through the development of a group of highly qualified experts, ERGA creates the foundation for continued advancement and creativity in the genomics sector. This manuscript also covers in detail the technological workflows and sequencing techniques used in ERGA's pilot infrastructure. With the aid of cutting-edge sequencing technologies based on both long-read and short-read sequencing, they are working to unravel the complex structure of the genetic code with a level of accuracy and precision never before possible. To guarantee the accuracy of genetic data and prevent mistakes and flaws that can jeopardize the findings' integrity, quality control methods are put in place. Despite having a focus on genome sequencing due to its technological complexities, ERGA also remains firm in its dedication to metadata collection and sample validation. Metadata serves as a critical link between raw genetic data and useful scientific insights, giving necessary context and allowing researchers to draw practical findings from their investigations. Sample validation approaches improve the reliability and reproducibility of the results, providing users confidence in the quality of the genetic data provided by ERGA. Looking ahead, ERGA envisions its decentralized infrastructure serving as a model for global collaborative research efforts. By embracing diversity, encouraging cooperation, and pushing for open access to data and resources, ERGA hopes to catalyze scientific discovery and generate positive change in the field of biodiversity genomics. ERGA aims to promote a more equitable and sustainable future for all by ongoing interaction with stakeholders, intensive outreach and education activities, and policy change advocacy. In addition to its immediate goals, ERGA considers the long-term implications of its work. As genomic technology progresses, the potential application of high-quality reference genomes will continue to grow. From informing conservation efforts and illuminating evolutionary histories to revolutionizing healthcare and agriculture, it is likely that ERGA's contributions will have far-reaching consequences for people and the planet as a whole. Furthermore, ERGA understands the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration in addressing the difficult challenges of the twenty-first century. ERGA aims to integrate genetic research into larger initiatives to promote sustainability and biodiversity conservation by forming relationships with stakeholders from other areas, such as policymakers, conservationists, and indigenous groups. Through shared knowledge and community action, ERGA seeks to create a future in which mankind coexists peacefully with the natural world, guided by a thorough grasp of its genetic legacy and ecological interconnectivity. Finally, the manuscript exemplifies ERGA's collaborative ambitions and achievements, capturing the spirit of creativity and collaboration that defines this ground-breaking effort. As ERGA continues to push the boundaries of genetic research, it remains dedicated to scientific excellence, inclusivity, and the quest of knowledge for the benefit of society. I wholeheartedly recommend the publication of this groundbreaking initiative, offering my enthusiastic endorsement for its valuable contribution to the scientific community. References Lewin, H. A., Robinson, G. E., Kress, W. J., Baker, W. J., Coddington, J., Crandall, K. A., Durbin, R., Edwards, S. V., Forest, F., Gilbert, M. T. P., Goldstein, M. M., Grigoriev, I. V., Hackett, K. J., Haussler, D., Jarvis, E. D., Johnson, W. E., Patrinos, A., Richards, S., Castilla-Rubio, J. C., … Zhang, G. (2018). Earth BioGenome Project: Sequencing life for the future of life. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(17), 4325–4333. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1720115115 Mazzoni, C. J., Claudio, C.i, Waterhouse, R. M. (2023). Biodiversity: an atlas of European reference genomes. Nature 619 : 252-252. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-02229-w Mc Cartney, A. M., Formenti, G., Mouton, A., Panis, D. de, Marins, L. S., Leitão, H. G., Diedericks, G., Kirangwa, J., Morselli, M., Salces-Ortiz, J., Escudero, N., Iannucci, A., Natali, C., Svardal, H., Fernández, R., Pooter, T. de, Joris, G., Strazisar, M., Wood, J., … Mazzoni, C. J. (2024). The European Reference Genome Atlas: piloting a decentralised approach to equitable biodiversity genomics. bioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.09.25.559365 | The European Reference Genome Atlas: piloting a decentralised approach to equitable biodiversity genomics | Ann M Mc Cartney, Giulio Formenti, Alice Mouton, Claudio Ciofi, Robert M Waterhouse, Camila J Mazzoni, Diego De Panis, Luisa S Schlude Marins, Henrique G Leitao, Genevieve Diedericks, Joseph Kirangwa, Marco Morselli, Judit Salces, Nuria Escudero, ... | <p>English: A global genome database of all of Earth's species diversity could be a treasure trove of scientific discoveries. However, regardless of the major advances in genome sequencing technologies, only a tiny fraction of species have genomic... |  | Bioinformatics, ERGA Pilot | Jitendra Narayan | Justin Ideozu, Eric Crandall | 2023-10-01 01:03:58 | View |

13 Jul 2024

High quality genome assembly and annotation (v1) of the eukaryotic terrestrial microalga Coccomyxa viridis SAG 216-4Anton Kraege, Edgar Chavarro-Carrero, Nadège Guiglielmoni, Eva Schnell, Joseph Kirangwa, Stefanie Heilmann-Heimbach, Kerstin Becker, Karl Köhrer, Philipp Schiffer, Bart P. H. J. Thomma, Hanna Rovenich https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.11.548521Reference genome for the lichen-forming green alga Coccomyxa viridis SAG 216–4Recommended by Iker Irisarri based on reviews by Elisa Goldbecker, Fabian Haas and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Elisa Goldbecker, Fabian Haas and 2 anonymous reviewers

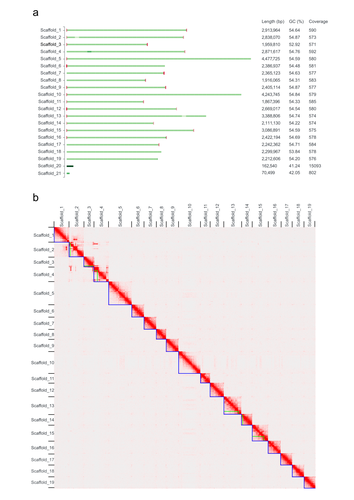

Green algae of the genus Coccomyxa (family Trebouxiophyceae) are extremely diverse in their morphology, habitat (i.e., in marine, freshwater, and terrestrial environments) and lifestyle, including free-living and mutualistic forms. Coccomyxa viridis (strain SAG 216–4) is a photobiont in the lichen Peltigera aphthosa, which was isolated in Switzerland more than 70 years ago (cf. SAG, the Culture Collection of Algae at the University of Göttingen, Germany). Despite the high diversity and plasticity in Coccomyxa, integrative taxonomic analyses led Darienko et al. (2015) to propose clear species boundaries. These authors also showed that symbiotic strains that form lichens evolved multiple times independently in Coccomyxa. Using state-of-the-art sequencing data and bioinformatic methods, including Pac-Bio HiFi and ONT long reads, as well as Hi-C chromatin conformation information, Kraege et al. (2024) generated a high-quality genome assembly for the Coccomyxa viridis strain SAG 216–4. They reconstructed 19 complete nuclear chromosomes, flanked by telomeric regions, totaling 50.9 Mb, plus the plastid and mitochondrial genomes. The performed quality controls leave no doubt of the high quality of the genome assemblies and structural annotations. An interesting observation is the lack of conserved synteny with the close relative Coccomyxa subellipsoidea, but further comparative studies with additional Coccomyxa strains will be required to grasp the genomic evolution in this genus of green algae. This project is framed within the ERGA pilot project, which aims to establish a pan-European genomics infrastructure and contribute to cataloging genomic biodiversity and producing resources that can inform conservation strategies (Formenti et al. 2022). This complete reference genome represents an important step towards this goal, in addition to contributing to future genomic analyses of Coccomyxa more generally.

References Darienko T, Gustavs L, Eggert A, Wolf W, Pröschold T (2015) Evaluating the species boundaries of green microalgae (Coccomyxa, Trebouxiophyceae, Chlorophyta) using integrative taxonomy and DNA barcoding with further implications for the species identification in environmental samples. PLOS ONE, 10, e0127838. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127838 Formenti G, Theissinger K, Fernandes C, Bista I, Bombarely A, Bleidorn C, Ciofi C, Crottini A, Godoy JA, Höglund J, Malukiewicz J, Mouton A, Oomen RA, Paez S, Palsbøll PJ, Pampoulie C, Ruiz-López MJ, Svardal H, Theofanopoulou C, de Vries J, Waldvogel A-M, Zhang G, Mazzoni CJ, Jarvis ED, Bálint M, European Reference Genome Atlas Consortium (2022) The era of reference genomes in conservation genomics. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 37, 197–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2021.11.008 Kraege A, Chavarro-Carrero EA, Guiglielmoni N, Schnell E, Kirangwa J, Heilmann-Heimbach S, Becker K, Köhrer K, WGGC Team, DeRGA Community, Schiffer P, Thomma BPHJ, Rovenich H (2024) High quality genome assembly and annotation (v1) of the eukaryotic terrestrial microalga Coccomyxa viridis SAG 216-4. bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.11.548521 | High quality genome assembly and annotation (v1) of the eukaryotic terrestrial microalga *Coccomyxa viridis* SAG 216-4 | Anton Kraege, Edgar Chavarro-Carrero, Nadège Guiglielmoni, Eva Schnell, Joseph Kirangwa, Stefanie Heilmann-Heimbach, Kerstin Becker, Karl Köhrer, Philipp Schiffer, Bart P. H. J. Thomma, Hanna Rovenich | <p>Unicellular green algae of the genus Coccomyxa are recognized for their worldwide distribution and ecological versatility. Most species described to date live in close association with various host species, such as in lichen associations. Howev... |  | ERGA Pilot | Iker Irisarri | 2023-11-09 11:54:43 | View | |

23 Mar 2022

Chromosomal rearrangements with stable repertoires of genes and transposable elements in an invasive forest-pathogenic fungusArthur Demene, Benoit Laurent, Sandrine Cros-Arteil, Christophe Boury, Cyril Dutech https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.09.434572Comparative genomics in the chestnut blight fungus Cryphonectria parasitica reveals large chromosomal rearrangements and a stable genome organizationRecommended by Sebastien Duplessis based on reviews by Benjamin Schwessinger and 1 anonymous reviewerAbout twenty-five years after the sequencing of the first fungal genome and a dozen years after the first plant pathogenic fungi genomes were sequenced, unprecedented international efforts have led to an impressive collection of genomes available for the community of mycologists in international databases (Goffeau et al. 1996, Dean et al. 2005; Spatafora et al. 2017). For instance, to date, the Joint Genome Institute Mycocosm database has collected more than 2,100 fungal genomes over the fungal tree of life (https://mycocosm.jgi.doe.gov). Such resources are paving the way for comparative genomics, population genomics and phylogenomics to address a large panel of questions regarding the biology and the ecology of fungal species. Early on, population genomics applied to pathogenic fungi revealed a great diversity of genome content and organization and a wide variety of variants and rearrangements (Raffaele and Kamoun 2012, Hartmann 2022). Such plasticity raises questions about how to choose a representative genome to serve as an ideal reference to address pertinent biological questions. Cryphonectria parasitica is a fungal pathogen that is infamous for the devastation of chestnut forests in North America after its accidental introduction more than a century ago (Anagnostakis 1987). Since then, it has been a quarantine species under surveillance in various parts of the world. As for other fungi causing diseases on forest trees, the study of adaptation to its host in the forest ecosystem and of its reproduction and dissemination modes is more complex than for crop-targeting pathogens. A first reference genome was published in 2020 for the chestnut blight fungus C. parasitica strain EP155 in the frame of an international project with the DOE JGI (Crouch et al. 2020). Another genome was then sequenced from the French isolate YVO003, which showed a few differences in the assembly suggesting possible rearrangements (Demené et al. 2019). Here the sequencing of a third isolate ESM015 from the native area of C. parasitica in Japan allows to draw broader comparative analysis and particularly to compare between native and introduced isolates (Demené et al. 2022). Demené and collaborators report on a new genome sequence using up-to-date long-read sequencing technologies and they provide an improved genome assembly. Comparison with previously published C. parasitica genomes did not reveal dramatic changes in the overall chromosomal landscapes, but large rearrangements could be spotted. Despite these rearrangements, the genome content and organization – i.e. genes and repeats – remain stable, with a limited number of genes gains and losses. As in any fungal plant pathogen genome, the repertoire of candidate effectors predicted among secreted proteins was more particularly scrutinized. Such effector genes have previously been reported in other pathogens in repeat-enriched plastic genomic regions with accelerated evolutionary rates under the pressure of the host immune system (Raffaele and Kamoun 2012). Demené and collaborators established a list of priority candidate effectors in the C. parasitica gene catalog likely involved in the interaction with the host plant which will require more attention in future functional studies. Six major inter-chromosomal translocations were detected and are likely associated with double break strands repairs. The authors speculate on the possible effects that these translocations may have on gene organization and expression regulation leading to dramatic phenotypic changes in relation to introduction and invasion in new continents and the impact regarding sexual reproduction in this fungus (Demené et al. 2022). I recommend this article not only because it is providing an improved assembly of a reference genome for C. parasitica, but also because it adds diversity in terms of genome references availability, with a third high-quality assembly. Such an effort in the tree pathology community for a pathogen under surveillance is of particular importance for future progress in post-genomic analysis, e.g. in further genomic population studies (Hartmann 2022). References Anagnostakis SL (1987) Chestnut Blight: The Classical Problem of an Introduced Pathogen. Mycologia, 79, 23–37. https://doi.org/10.2307/3807741 Crouch JA, Dawe A, Aerts A, Barry K, Churchill ACL, Grimwood J, Hillman BI, Milgroom MG, Pangilinan J, Smith M, Salamov A, Schmutz J, Yadav JS, Grigoriev IV, Nuss DL (2020) Genome Sequence of the Chestnut Blight Fungus Cryphonectria parasitica EP155: A Fundamental Resource for an Archetypical Invasive Plant Pathogen. Phytopathology®, 110, 1180–1188. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-12-19-0478-A Dean RA, Talbot NJ, Ebbole DJ, Farman ML, Mitchell TK, Orbach MJ, Thon M, Kulkarni R, Xu J-R, Pan H, Read ND, Lee Y-H, Carbone I, Brown D, Oh YY, Donofrio N, Jeong JS, Soanes DM, Djonovic S, Kolomiets E, Rehmeyer C, Li W, Harding M, Kim S, Lebrun M-H, Bohnert H, Coughlan S, Butler J, Calvo S, Ma L-J, Nicol R, Purcell S, Nusbaum C, Galagan JE, Birren BW (2005) The genome sequence of the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Nature, 434, 980–986. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03449 Demené A., Laurent B., Cros-Arteil S., Boury C. and Dutech C. 2022. Chromosomal rearrangements with stable repertoires of genes and transposable elements in an invasive forest-pathogenic fungus. bioRxiv, 2021.03.09.434572, ver.6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.09.434572 Goffeau A, Barrell BG, Bussey H, Davis RW, Dujon B, Feldmann H, Galibert F, Hoheisel JD, Jacq C, Johnston M, Louis EJ, Mewes HW, Murakami Y, Philippsen P, Tettelin H, Oliver SG (1996) Life with 6000 Genes. Science, 274, 546–567. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.274.5287.546 Hartmann FE (2022) Using structural variants to understand the ecological and evolutionary dynamics of fungal plant pathogens. New Phytologist, 234, 43–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.17907 Raffaele S, Kamoun S (2012) Genome evolution in filamentous plant pathogens: why bigger can be better. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 10, 417–430. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2790 Spatafora JW, Aime MC, Grigoriev IV, Martin F, Stajich JE, Blackwell M (2017) The Fungal Tree of Life: from Molecular Systematics to Genome-Scale Phylogenies. Microbiology Spectrum, 5, 5.5.03. https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.FUNK-0053-2016 | Chromosomal rearrangements with stable repertoires of genes and transposable elements in an invasive forest-pathogenic fungus | Arthur Demene, Benoit Laurent, Sandrine Cros-Arteil, Christophe Boury, Cyril Dutech | <p style="text-align: justify;">Chromosomal rearrangements have been largely described among eukaryotes, and may have important consequences on evolution of species. High genome plasticity has been often reported in Fungi, which may explain their ... |  | Evolutionary genomics, Fungi | Sebastien Duplessis | 2021-03-12 14:18:20 | View | |

01 Jul 2024

Contextualising samples: Supporting reference genomes of European biodiversity through sample and associated metadata collectionAstrid Böhne, Rosa Fernández, Jennifer A. Leonard, Ann M. McCartney, Seanna McTaggart, José Melo-Ferreira, Rita Monteiro, Rebekah A. Oomen, Olga Vinnere Pettersson, Torsten H. Struck https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.28.546652To avoid biases and to be FAIR, we need to CARE and share biodiversity metadataRecommended by Francois Sabot based on reviews by Julian Osuji and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Julian Osuji and 1 anonymous reviewer

Böhne et al. (2024) do not present a classical scientific paper per se but a report on how the European Reference Genome Atlas (ERGA) aims to deal with sampling and sample information, i.e. metadata. As the goal of ERGA is to provide an almost fully representative set of reference genomes representative of European biodiversity to serve many research areas in biology, they have to be really exhaustive. In this regard, in addition to providing sample metadata recording guidelines, they also discuss the biases existing in sampling and sequencing projects. The first task for such a project is to be sure that the data they generate will be usable and available in the future (“[in] perpetuity", Böhne et al. 2024). The authors deployed a very efficient pipeline for conserving information on sampling: location, physical information, copies of tissues and of DNA, shipping, legal/ethical aspects regarding the Nagoya Protocol, etc., alongside a best-practice manual. This effort is linked to practical guides for the DNA extraction of specific taxa. More generally, these details enable “Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable” (FAIR) principles (Wilkinson et al. 2016) to be followed. An important aspect of this paper, in addition to practical points, is the reflection upon the different biases inherent to the choice of sequenced samples. Acknowledging their own biases with regards to DNA extraction protocol efficiency, small genome size choice, as well as the availability of material (Nagoya Protocol aspects) and material transfer efficiency, the authors recommend in the future to not survey biodiversity by selecting one’s favorite samples or species, but also considering "orphan" taxa. Some of these "orphan" taxonomic groups belong to non-arthropod invertebrates but internal disparities are also prominent within other taxa. Finally, the implementation of the "Collective benefit, Authority to control, Responsibility, and Ethics" (CARE) principles (Carroll et al. 2021) will allow Indigenous rights to be considered when prioritizing samples, and to enable their "knowledge systems to permeate throughout the process of reference genome production and beyond" (Böhne et al. 2024). Last, but not least, as ERGA, including its Sampling and Sample Processing committee, is a large collective effort, it is very refreshing to read a paper starting with the acknowledgements and the roles of each member.

References Böhne A, Fernández R, Leonard JA, McCartney AM, McTaggart S, Melo-Ferreira J, Monteiro R, Oomen RA, Pettersson OV, Struck TH (2024) Contextualising samples: Supporting reference genomes of European biodiversity through sample and associated metadata collection. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.28.546652 Carroll SR, Herczog E, Hudson M, Russell K, Stall S (2021) Operationalizing the CARE and FAIR Principles for Indigenous data futures. Scientific Data, 8, 108. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-021-00892-0 Wilkinson MD, Dumontier M, Aalbersberg IjJ, Appleton G, Axton M, Baak A, Blomberg N, Boiten J-W, da Silva Santos LB, Bourne PE, Bouwman J, Brookes AJ, Clark T, Crosas M, Dillo I, Dumon O, Edmunds S, Evelo CT, Finkers R, Gonzalez-Beltran A, Gray AJG, Groth P, Goble C, Grethe JS, Heringa J, ’t Hoen PAC, Hooft R, Kuhn T, Kok R, Kok J, Lusher SJ, Martone ME, Mons A, Packer AL, Persson B, Rocca-Serra P, Roos M, van Schaik R, Sansone S-A, Schultes E, Sengstag T, Slater T, Strawn G, Swertz MA, Thompson M, van der Lei J, van Mulligen E, Velterop J, Waagmeester A, Wittenburg P, Wolstencroft K, Zhao J, Mons B (2016) The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data, 3, 160018. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18 | Contextualising samples: Supporting reference genomes of European biodiversity through sample and associated metadata collection | Astrid Böhne, Rosa Fernández, Jennifer A. Leonard, Ann M. McCartney, Seanna McTaggart, José Melo-Ferreira, Rita Monteiro, Rebekah A. Oomen, Olga Vinnere Pettersson, Torsten H. Struck | <p>The European Reference Genome Atlas (ERGA) consortium aims to generate a reference genome catalogue for all of Europe's eukaryotic biodiversity. The biological material underlying this mission, the specimens and their derived samples, are provi... |  | ERGA, ERGA BGE, ERGA Pilot, Evolutionary genomics | Francois Sabot | Julian Osuji, Francois Sabot, Anonymous | 2023-07-03 10:39:36 | View |

24 Feb 2023

MacSyFinder v2: Improved modelling and search engine to identify molecular systems in genomesBertrand Néron, Rémi Denise, Charles Coluzzi, Marie Touchon, Eduardo P. C. Rocha, Sophie S. Abby https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.02.506364A unique and customizable approach for functionally annotating prokaryotic genomesRecommended by Gavin Douglas based on reviews by Kwee Boon Brandon Seah and Max Emil Schön based on reviews by Kwee Boon Brandon Seah and Max Emil Schön

Macromolecular System Finder (MacSyFinder) v2 (Néron et al., 2023) is a newly updated approach for performing functional annotation of prokaryotic genomes (Abby et al., 2014). This tool parses an input file of protein sequences from a single genome (either ordered by genome location or unordered) and identifies the presence of specific cellular functions (referred to as “systems”). These systems are called based on two criteria: (1) that the "quorum" of a minimum set of core proteins involved is reached the “quorum” of a minimum set of core proteins being involved that are present, and (2) that the genes encoding these proteins are in the expected genomic organization (e.g., within the same order in an operon), when ordered data is provided. I believe the MacSyFinder approach represents an improvement over more commonly used methods exactly because it can incorporate such information on genomic organization, and also because it is more customizable. Before properly appreciating these points, it is worth noting the norms and key challenges surrounding high-throughput functional annotation of prokaryotic genomes. Genome sequences are being added to online repositories at increasing rates, which has led to an enormous amount of bacterial genome diversity available to investigate (Altermann et al., 2022). A key aspect of understanding this diversity is the functional annotation step, which enables genes to be grouped into more biologically interpretable categories. For instance, gene calls can be mapped against existing Clusters of Orthologous Genes, which are themselves grouped into general categories such as ‘Transcription’ and ‘Lipid metabolism’ (Galperin et al., 2021). This approach is valuable but is primarily used for global summaries of functional annotations within a genome: for example, it could be useful to know that a genome is particularly enriched for genes involved in lipid metabolism. However, knowing that a particular gene is involved in the general process of lipid metabolism is less likely to be actionable. In other words, the desired specificity of a gene’s functional annotation will depend on the exact question being investigated. There is no shortage of functional ontologies in genomics that can be applied for this purpose (Douglas and Langille, 2021), and researchers are often overwhelmed by the choice of which functional ontology to use. In this context, giving researchers the ability to precisely specify the gene families and operon structures they are interested in identifying across genomes provides useful control over what precise functions they are profiling. Of course, most researchers will lack the information and/or expertise to fully take advantage of MacSyFinder’s customizable features, but having this option for specialized purposes is valuable. The other MacSyFinder feature that I find especially noteworthy is that it can incorporate genomic organization (e.g., of genes ordered in operons) when calling systems. This is a rare feature among commonly used tools for functional annotation and likely results in much higher specificity. As the authors note, this capability makes the co-occurrence of paralogs, and other divergent genes that share sequence similarity, to contribute less noise (i.e., they result in fewer false positive calls). It is important to emphasize that these features are not new additions in MacSyFinder v2, but there are many other valuable changes. Most practically, this release is written in Python 3, rather than the obsolete Python 2.7, and was made more computationally efficient, which will enable MacSyFinder to be more widely used and more easily maintained moving forward. In addition, the search algorithm for analyzing individual proteins was fundamentally updated as well. The authors show that their improvements to the search algorithm result in an 8% and 20% increase in the number of identified calls for single and multi-locus secretion systems, respectively. Taken together, MacSyFinder v2 represents both practical and scientific improvements over the previous version, which will be of great value to the field. References Abby SS, Néron B, Ménager H, Touchon M, Rocha EPC (2014) MacSyFinder: A Program to Mine Genomes for Molecular Systems with an Application to CRISPR-Cas Systems. PLOS ONE, 9, e110726. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0110726 Altermann E, Tegetmeyer HE, Chanyi RM (2022) The evolution of bacterial genome assemblies - where do we need to go next? Microbiome Research Reports, 1, 15. https://doi.org/10.20517/mrr.2022.02 Douglas GM, Langille MGI (2021) A primer and discussion on DNA-based microbiome data and related bioinformatics analyses. Peer Community Journal, 1. https://doi.org/10.24072/pcjournal.2 Galperin MY, Wolf YI, Makarova KS, Vera Alvarez R, Landsman D, Koonin EV (2021) COG database update: focus on microbial diversity, model organisms, and widespread pathogens. Nucleic Acids Research, 49, D274–D281. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa1018 Néron B, Denise R, Coluzzi C, Touchon M, Rocha EPC, Abby SS (2023) MacSyFinder v2: Improved modelling and search engine to identify molecular systems in genomes. bioRxiv, 2022.09.02.506364, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.02.506364 | MacSyFinder v2: Improved modelling and search engine to identify molecular systems in genomes | Bertrand Néron, Rémi Denise, Charles Coluzzi, Marie Touchon, Eduardo P. C. Rocha, Sophie S. Abby | <p style="text-align: justify;">Complex cellular functions are usually encoded by a set of genes in one or a few organized genetic loci in microbial genomes. Macromolecular System Finder (MacSyFinder) is a program that uses these properties to mod... |  | Bacteria and archaea, Bioinformatics, Functional genomics | Gavin Douglas | Kwee Boon Brandon Seah, Max Emil Schön | 2022-09-09 10:30:31 | View |