Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender▲ | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

26 Jun 2024

Transposable element expression with variation in sex chromosome number supports a toxic Y effect on human longevityJordan Teoli, Miriam Merenciano, Marie Fablet, Anamaria Necsulea, Daniel Siqueira-de-Oliveira, Alessandro Brandulas-Cammarata, Audrey Labalme, Hervé Lejeune, Jean-François Lemaitre, François Gueyffier, Damien Sanlaville, Claire Bardel, Cristina Vieira, Gabriel AB Marais, Ingrid Plotton https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.03.550779The number of Y chromosomes is positively associated with transposable element expression in humans, in line with the toxic Y hypothesisRecommended by Anna-Sophie Fiston-Lavier based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers

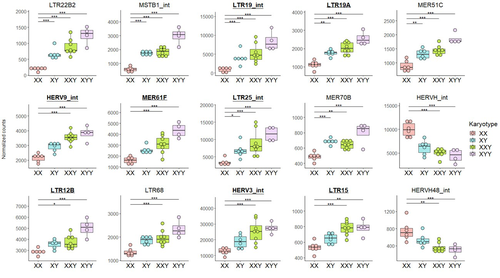

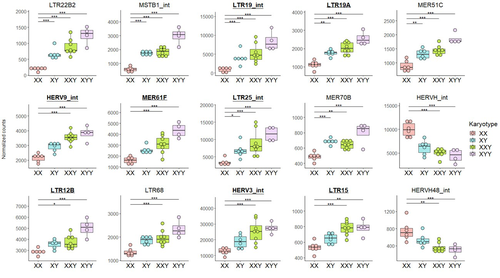

The study of human longevity has long been a source of fascination for scientists, particularly in relation to the genetic factors that contribute to differences in lifespan between the sexes. One particularly intriguing area of research concerns the Y chromosome and its impact on male longevity. The Y chromosome expresses genes that are essential for male development and reproduction. However, it may also influence various physiological processes and health outcomes. It is therefore of great importance to investigate the impact of the Y chromosome on longevity. This may assist in elucidating the biological mechanisms underlying sex-specific differences in aging and disease susceptibility. As longevity research progresses, the Y chromosome's role presents a promising avenue for elucidating the complex interplay between genetics and aging. Transposable elements (TEs), often referred to as "jumping genes", are DNA sequences that can move within the genome, potentially causing mutations and genomic instability. In young, healthy cells, various mechanisms, including DNA methylation and histone modifications, suppress TE activity to maintain genomic integrity. However, as individuals age, these regulatory mechanisms may deteriorate, leading to increased TE activity. This dysregulation could contribute to age-related genomic instability, cellular dysfunction, and the onset of diseases such as cancer. Understanding how TE repression changes with age is crucial for uncovering the molecular underpinnings of aging (De Cecco et al. 2013; Van Meter et al. 2014). The lower recombination rates observed on Y chromosomes result in the accumulation of TE insertions, which in turn leads to an enrichment of TEs and potentially higher TE activity. To ascertain whether the number of Y chromosomes is associated with TE activity in humans, Teoli et al. (2024) studied the TE expression level, as a proxy of the TE activity, in several karyotype compositions (i.e. with differing numbers of Y chromosomes). They used transcriptomic data from blood samples collected in 24 individuals (six females 46,XX, six males 46,XY, eight males 47,XXY and four males 47,XYY). Even though they did not observe a significant correlation between the number of Y chromosomes and TE expression, their results suggest an impact of the presence of the Y chromosome on the overall TE expression. The presence of Y chromosomes also affected the type (family) of TE present/expressed. To ensure that the TE expression level was not biased by the expression of a gene in proximity due to intron retention or pervasive intragenic transcription, the authors also tested whether the TE expression variation observed between the different karyotypes could be explained by gene (i.e. here non-TE gene) expression. As TE repression mechanisms are known to decrease over time, the authors also tested whether TE repression is weaker in older individuals, which would support a compelling link between genomic stability and aging. They investigated the TE expression differently between males and females, hypothesizing that old males should exhibit a stronger TE activity than old females. Using selected 45 males (47,XY) and 35 females (46,XX) blood samples of various ages (from 20 to 70) from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project, the authors studied the effect of age on TE expression using 10-year range to group the study subjects. Based on these data, they fail to find an overall increase of TE expression in old males compared to old females. Notwithstanding the small number of samples, the study is well-designed and innovative, and its findings are highly promising. It marks an initial step towards understanding the impact of Y-chromosome ‘toxicity’ on human longevity. Despite the relatively small sample size, which is a consequence of the difficulty of obtaining samples from individuals with sex chromosome aneuploidies, the results are highly intriguing and will be of interest to a broad range of biologists.

References De Cecco M, Criscione SW, Peckham EJ, Hillenmeyer S, Hamm EA, Manivannan J, Peterson AL, Kreiling JA, Neretti N, Sedivy JM (2013) Genomes of replicatively senescent cells undergo global epigenetic changes leading to gene silencing and activation of transposable elements. Aging Cell, 12, 247–256. https://doi.org/10.1111/acel.12047 Teoli J, Merenciano M, Fablet M, Necsulea A, Siqueira-de-Oliveira D, Brandulas-Cammarata A, Labalme A, Lejeune H, Lemaitre J-F, Gueyffier F, Sanlaville D, Bardel C, Vieira C, Marais GAB, Plotton I (2024) Transposable element expression with variation in sex chromosome number supports a toxic Y effect on human longevity. bioRxiv, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.03.550779 Van Meter M, Kashyap M, Rezazadeh S, Geneva AJ, Morello TD, Seluanov A, Gorbunova V (2014) SIRT6 represses LINE1 retrotransposons by ribosylating KAP1 but this repression fails with stress and age. Nature Communications, 5, 5011. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6011

| Transposable element expression with variation in sex chromosome number supports a toxic Y effect on human longevity | Jordan Teoli, Miriam Merenciano, Marie Fablet, Anamaria Necsulea, Daniel Siqueira-de-Oliveira, Alessandro Brandulas-Cammarata, Audrey Labalme, Hervé Lejeune, Jean-François Lemaitre, François Gueyffier, Damien Sanlaville, Claire Bardel, Cristina Vi... | <p>Why women live longer than men is still an open question in human biology. Sex chromosomes have been proposed to play a role in the observed sex gap in longevity, and the Y male chromosome has been suspected of having a potential toxic genomic ... |  | Evolutionary genomics | Anna-Sophie Fiston-Lavier | Anonymous, Igor Rogozin , Paul Jay , Anonymous | 2023-08-18 15:01:38 | View |

27 Apr 2021

Uncovering transposable element variants and their potential adaptive impact in urban populations of the malaria vector Anopheles coluzziiCarlos Vargas-Chavez, Neil Michel Longo Pendy, Sandrine E. Nsango, Laura Aguilera, Diego Ayala, and Josefa González https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.22.393231Anopheles coluzzii, a new system to study how transposable elements may foster adaptation to urban environmentsRecommended by Anne Roulin based on reviews by Yann Bourgeois and 1 anonymous reviewerTransposable elements (TEs) are mobile DNA sequences that can increase their copy number and move from one location to another within the genome [1]. Because of their transposition dynamics, TEs constitute a significant fraction of eukaryotic genomes. TEs are also known to play an important functional role and a wealth of studies has now reported how TEs may influence single host traits [e.g. 2–4]. Given that TEs are more likely than classical point mutations to cause extreme changes in gene expression and phenotypes, they might therefore be especially prone to produce the raw diversity necessary for individuals to respond to challenging environments [5,6] such as the ones found in urban area.

| Uncovering transposable element variants and their potential adaptive impact in urban populations of the malaria vector Anopheles coluzzii | Carlos Vargas-Chavez, Neil Michel Longo Pendy, Sandrine E. Nsango, Laura Aguilera, Diego Ayala, and Josefa González | <p style="text-align: justify;">Background</p> <p style="text-align: justify;">Anopheles coluzzii is one of the primary vectors of human malaria in sub-Saharan Africa. Recently, it has colonized the main cities of Central Africa threatening vecto... |  | Evolutionary genomics | Anne Roulin | 2020-12-02 14:58:47 | View | |

24 Sep 2020

A rapid and simple method for assessing and representing genome sequence relatednessM Briand, M Bouzid, G Hunault, M Legeay, M Fischer-Le Saux, M Barret https://doi.org/10.1101/569640A quick alternative method for resolving bacterial taxonomy using short identical DNA sequences in genomes or metagenomesRecommended by B. Jesse Shapiro based on reviews by Gavin Douglas and 1 anonymous reviewerThe bacterial species problem can be summarized as follows: bacteria recombine too little, and yet too much (Shapiro 2019). References Arevalo P, VanInsberghe D, Elsherbini J, Gore J, Polz MF (2019) A Reverse Ecology Approach Based on a Biological Definition of Microbial Populations. Cell, 178, 820-834.e14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2019.06.033 | A rapid and simple method for assessing and representing genome sequence relatedness | M Briand, M Bouzid, G Hunault, M Legeay, M Fischer-Le Saux, M Barret | <p>Coherent genomic groups are frequently used as a proxy for bacterial species delineation through computation of overall genome relatedness indices (OGRI). Average nucleotide identity (ANI) is a widely employed method for estimating relatedness ... |  | Bioinformatics, Metagenomics | B. Jesse Shapiro | Gavin Douglas | 2019-11-07 16:37:56 | View |

07 Oct 2021

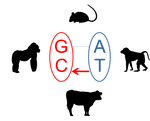

Fine-scale quantification of GC-biased gene conversion intensity in mammalsNicolas Galtier https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.05.442789A systematic approach to the study of GC-biased gene conversion in mammalsRecommended by Carina Farah Mugal based on reviews by Fanny Pouyet , David Castellano and 1 anonymous reviewerThe role of GC-biased gene conversion (gBGC) in molecular evolution has interested scientists for the last two decades since its discovery in 1999 (Eyre-Walker 1999; Galtier et al. 2001). gBGC is a process that is associated with meiotic recombination, and is characterized by a transmission distortion in favor of G and C over A and T alleles at GC/AT heterozygous sites that occur in the vicinity of recombination-inducing double-strand breaks (Duret and Galtier 2009; Mugal et al. 2015). This transmission distortion results in a fixation bias of G and C alleles, equivalent to directional selection for G and C (Nagylaki 1983). The fixation bias subsequently leads to a correlation between recombination rate and GC content across the genome, which has served as indirect evidence for the prevalence of gBGC in many organisms. The fixation bias also produces shifts in the allele frequency spectrum (AFS) towards higher frequencies of G and C alleles. These molecular signatures of gBGC provide a means to quantify the strength of gBGC and study its variation among species and across the genome. Following this idea, first Lartillot (2013) and Capra et al. (2013) developed phylogenetic methodology to quantify gBGC based on substitutions, and De Maio et al. (2013) combined information on polymorphism into a phylogenetic setting. Complementary to the phylogenetic methods, later Glemin et al. (2015) developed a method that draws information solely from polymorphism data and the shape of the AFS. Application of these methods to primates (Capra et al. 2013; De Maio et al. 2013; Glemin et al. 2015) and mammals (Lartillot 2013) supported the notion that variation in the strength of gBGC across the genome reflects the dynamics of the recombination landscape, while variation among species correlates with proxies of the effective population size. However, application of the polymorphism-based method by Glemin et al. (2015) to distantly related Metazoa did not confirm the correlation with effective population size (Galtier et al. 2018). Here, Galtier (2021) introduces a novel phylogenetic approach applicable to the study of closely related species. Specifically, Galtier introduces a statistical framework that enables the systematic study of variation in the strength of gBGC among species and among genes. In addition, Galtier assesses fine-scale variation of gBGC across the genome by means of spatial autocorrelation analysis. This puts Galtier in a position to study variation in the strength of gBGC at three different scales, i) among species, ii) among genes, and iii) within genes. Galtier applies his method to four families of mammals, Hominidae, Cercopithecidae, Bovidae, and Muridae and provides a thorough discussion of his findings and methodology. Galtier found that the strength of gBGC correlates with proxies of the effective population size (Ne), but that the slope of the relationship differs among the four families of mammals. Given the relationship between the population-scaled strength of gBGC B = 4Neb, this finding suggests that the conversion bias (b) could vary among mammalian species. Variation in b could either result from differences in the strength of the transmission distortion (Galtier et al. 2018) or evolutionary changes in the rate of recombination (Boman et al. 2021). Alternatively, Galtier suggests that also systematic variation in proxies of Ne could lead to similar observations. Finally, the present study reports intriguing inter-species differences between the extent of variation in the strength of gBGC among and within genes, which are interpreted in consideration of the recombination dynamics in mammals. References Boman J, Mugal CF, Backström N (2021) The Effects of GC-Biased Gene Conversion on Patterns of Genetic Diversity among and across Butterfly Genomes. Genome Biology and Evolution, 13. https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evab064 Capra JA, Hubisz MJ, Kostka D, Pollard KS, Siepel A (2013) A Model-Based Analysis of GC-Biased Gene Conversion in the Human and Chimpanzee Genomes. PLOS Genetics, 9, e1003684. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003684 De Maio N, Schlötterer C, Kosiol C (2013) Linking Great Apes Genome Evolution across Time Scales Using Polymorphism-Aware Phylogenetic Models. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 30, 2249–2262. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/mst131 Duret L, Galtier N (2009) Biased Gene Conversion and the Evolution of Mammalian Genomic Landscapes. Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics, 10, 285–311. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-genom-082908-150001 Eyre-Walker A (1999) Evidence of Selection on Silent Site Base Composition in Mammals: Potential Implications for the Evolution of Isochores and Junk DNA. Genetics, 152, 675–683. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/152.2.675 Galtier N (2021) Fine-scale quantification of GC-biased gene conversion intensity in mammals. bioRxiv, 2021.05.05.442789, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.05.442789 Galtier N, Piganeau G, Mouchiroud D, Duret L (2001) GC-Content Evolution in Mammalian Genomes: The Biased Gene Conversion Hypothesis. Genetics, 159, 907–911. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/159.2.907 Galtier N, Roux C, Rousselle M, Romiguier J, Figuet E, Glémin S, Bierne N, Duret L (2018) Codon Usage Bias in Animals: Disentangling the Effects of Natural Selection, Effective Population Size, and GC-Biased Gene Conversion. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 35, 1092–1103. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy015 Glémin S, Arndt PF, Messer PW, Petrov D, Galtier N, Duret L (2015) Quantification of GC-biased gene conversion in the human genome. Genome Research, 25, 1215–1228. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.185488.114 Lartillot N (2013) Phylogenetic Patterns of GC-Biased Gene Conversion in Placental Mammals and the Evolutionary Dynamics of Recombination Landscapes. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 30, 489–502. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/mss239 Mugal CF, Weber CC, Ellegren H (2015) GC-biased gene conversion links the recombination landscape and demography to genomic base composition. BioEssays, 37, 1317–1326. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.201500058 Nagylaki T (1983) Evolution of a finite population under gene conversion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 80, 6278–6281. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.80.20.6278 | Fine-scale quantification of GC-biased gene conversion intensity in mammals | Nicolas Galtier | <p style="text-align: justify;">GC-biased gene conversion (gBGC) is a molecular evolutionary force that favours GC over AT alleles irrespective of their fitness effect. Quantifying the variation in time and across genomes of its intensity is key t... |  | Evolutionary genomics, Population genomics, Vertebrates | Carina Farah Mugal | 2021-05-25 09:25:52 | View | |

05 May 2021

A primer and discussion on DNA-based microbiome data and related bioinformatics analysesGavin M. Douglas and Morgan G. I. Langille https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/3dybgA hitchhiker’s guide to DNA-based microbiome analysisRecommended by Danny Ionescu based on reviews by Nicolas Pollet, Rafael Cuadrat and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Nicolas Pollet, Rafael Cuadrat and 1 anonymous reviewer

In the last two decades, microbial research in its different fields has been increasingly focusing on microbiome studies. These are defined as studies of complete assemblages of microorganisms in given environments and have been benefiting from increases in sequencing length, quality, and yield, coupled with ever-dropping prices per sequenced nucleotide. Alongside localized microbiome studies, several global collaborative efforts have emerged, including the Human Microbiome Project [1], the Earth Microbiome Project [2], the Extreme Microbiome Project, and MetaSUB [3]. Coupled with the development of sequencing technologies and the ever-increasing amount of data output, multiple standalone or online bioinformatic tools have been designed to analyze these data. Often these tools have been focusing on either of two main tasks: 1) Community analysis, providing information on the organisms present in the microbiome, or 2) Functionality, in the case of shotgun metagenomic data, providing information on the metabolic potential of the microbiome. Bridging between the two types of data, often extracted from the same dataset, is typically a daunting task that has been addressed by a handful of tools only. The extent of tools and approaches to analyze microbiome data is great and may be overwhelming to researchers new to microbiome or bioinformatic studies. In their paper “A primer and discussion on DNA-based microbiome data and related bioinformatics analyses”, Douglas and Langille [4] guide us through the different sequencing approaches useful for microbiome studies. alongside their advantages and caveats and a selection of tools to analyze these data, coupled with examples from their own field of research. Standing out in their primer-style review is the emphasis on the coupling between taxonomic/phylogenetic identification of the organisms and their functionality. This type of analysis, though highly important to understand the role of different microorganisms in an environment as well as to identify potential functional redundancy, is often not conducted. For this, the authors identify two approaches. The first, using shotgun metagenomics, has higher chances of attributing a function to the correct taxon. The second, using amplicon sequencing of marker genes, allows for a deeper coverage of the microbiome at a lower cost, and extrapolates the amplicon data to close relatives with a sequenced genome. As clearly stated, this approach makes the leap between taxonomy and functionality and has been shown to be erroneous in cases where the core genome of the bacterial genus or family does not encompass the functional diversity of the different included species. This practice was already common before the genomic era, but its accuracy is improving thanks to the increasing availability of sequenced reference genomes from cultures, environmentally picked single cells or metagenome-assembled genome. In addition to their description of standalone tools useful for linking taxonomy and functionality, one should mention the existence of online tools that may appeal to researchers who do not have access to adequate bioinformatics infrastructure. Among these are the Integrated Microbial Genomes and Microbiomes (IMG) from the Joint Genome Institute [5], KBase [6] and MG-RAST [7]. A second important point arising from this review is the need for standardization in microbiome data analyses and the complexity of achieving this. As Douglas and Langille [4] state, this has been previously addressed, highlighting the variability in results obtained with different tools. It is often the case that papers describing new bioinformatic tools display their superiority relative to existing alternatives, potentially misleading newcomers to the field that the newest tool is the best and only one to be used. This is often not the case, and while benchmarking against well-defined datasets serves as a powerful testing tool, “real-life” samples are often not comparable. Thus, as done here, future primer-like reviews should highlight possible cross-field caveats, encouraging researchers to employ and test several approaches and validate their results whenever possible. In summary, Douglas and Langille [4] offer both the novice and experienced researcher a detailed guide along the paths of microbiome data analysis, accompanied by informative background information, suggested tools with which analyses can be started, and an insightful view on where the field should be heading. References [1] Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Hamady M, Fraser-Liggett CM, Knight R, Gordon JI (2007) The Human Microbiome Project. Nature, 449, 804–810. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06244 [2] Gilbert JA, Jansson JK, Knight R (2014) The Earth Microbiome project: successes and aspirations. BMC Biology, 12, 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-014-0069-1 [3] Mason C, Afshinnekoo E, Ahsannudin S, Ghedin E, Read T, Fraser C, Dudley J, Hernandez M, Bowler C, Stolovitzky G, Chernonetz A, Gray A, Darling A, Burke C, Łabaj PP, Graf A, Noushmehr H, Moraes s., Dias-Neto E, Ugalde J, Guo Y, Zhou Y, Xie Z, Zheng D, Zhou H, Shi L, Zhu S, Tang A, Ivanković T, Siam R, Rascovan N, Richard H, Lafontaine I, Baron C, Nedunuri N, Prithiviraj B, Hyat S, Mehr S, Banihashemi K, Segata N, Suzuki H, Alpuche Aranda CM, Martinez J, Christopher Dada A, Osuolale O, Oguntoyinbo F, Dybwad M, Oliveira M, Fernandes A, Oliveira M, Fernandes A, Chatziefthimiou AD, Chaker S, Alexeev D, Chuvelev D, Kurilshikov A, Schuster S, Siwo GH, Jang S, Seo SC, Hwang SH, Ossowski S, Bezdan D, Udekwu K, Udekwu K, Lungjdahl PO, Nikolayeva O, Sezerman U, Kelly F, Metrustry S, Elhaik E, Gonnet G, Schriml L, Mongodin E, Huttenhower C, Gilbert J, Hernandez M, Vayndorf E, Blaser M, Schadt E, Eisen J, Beitel C, Hirschberg D, Schriml L, Mongodin E, The MetaSUB International Consortium (2016) The Metagenomics and Metadesign of the Subways and Urban Biomes (MetaSUB) International Consortium inaugural meeting report. Microbiome, 4, 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-016-0168-z [4] Douglas GM, Langille MGI (2021) A primer and discussion on DNA-based microbiome data and related bioinformatics analyses. OSF Preprints, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Genomics. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/3dybg [5] Chen I-MA, Markowitz VM, Chu K, Palaniappan K, Szeto E, Pillay M, Ratner A, Huang J, Andersen E, Huntemann M, Varghese N, Hadjithomas M, Tennessen K, Nielsen T, Ivanova NN, Kyrpides NC (2017) IMG/M: integrated genome and metagenome comparative data analysis system. Nucleic Acids Research, 45, D507–D516. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw929 [6] Arkin AP, Cottingham RW, Henry CS, Harris NL, Stevens RL, Maslov S, Dehal P, Ware D, Perez F, Canon S, Sneddon MW, Henderson ML, Riehl WJ, Murphy-Olson D, Chan SY, Kamimura RT, Kumari S, Drake MM, Brettin TS, Glass EM, Chivian D, Gunter D, Weston DJ, Allen BH, Baumohl J, Best AA, Bowen B, Brenner SE, Bun CC, Chandonia J-M, Chia J-M, Colasanti R, Conrad N, Davis JJ, Davison BH, DeJongh M, Devoid S, Dietrich E, Dubchak I, Edirisinghe JN, Fang G, Faria JP, Frybarger PM, Gerlach W, Gerstein M, Greiner A, Gurtowski J, Haun HL, He F, Jain R, Joachimiak MP, Keegan KP, Kondo S, Kumar V, Land ML, Meyer F, Mills M, Novichkov PS, Oh T, Olsen GJ, Olson R, Parrello B, Pasternak S, Pearson E, Poon SS, Price GA, Ramakrishnan S, Ranjan P, Ronald PC, Schatz MC, Seaver SMD, Shukla M, Sutormin RA, Syed MH, Thomason J, Tintle NL, Wang D, Xia F, Yoo H, Yoo S, Yu D (2018) KBase: The United States Department of Energy Systems Biology Knowledgebase. Nature Biotechnology, 36, 566–569. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.4163 [7] Wilke A, Bischof J, Gerlach W, Glass E, Harrison T, Keegan KP, Paczian T, Trimble WL, Bagchi S, Grama A, Chaterji S, Meyer F (2016) The MG-RAST metagenomics database and portal in 2015. Nucleic Acids Research, 44, D590–D594. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv1322 | A primer and discussion on DNA-based microbiome data and related bioinformatics analyses | Gavin M. Douglas and Morgan G. I. Langille | <p style="text-align: justify;">The past decade has seen an eruption of interest in profiling microbiomes through DNA sequencing. The resulting investigations have revealed myriad insights and attracted an influx of researchers to the research are... |  | Bioinformatics, Metagenomics | Danny Ionescu | 2021-02-17 00:26:46 | View | |

06 Apr 2021

Evidence for shared ancestry between Actinobacteria and Firmicutes bacteriophagesMatthew Koert, Júlia López-Pérez, Courtney Mattson, Steven M. Caruso, Ivan Erill https://doi.org/10.1101/842583Viruses of bacteria: phages evolution across phylum boundariesRecommended by Denis Tagu based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersBacteria and phages have coexisted and coevolved for a long time. Phages are bacteria-infecting viruses, with a symbiotic status sensu lato, meaning they can be pathogenic, commensal or mutualistic. Thus, the association between bacteria phages has probably played a key role in the high adaptability of bacteria to most - if not all – of Earth’s ecosystems, including other living organisms (such as eukaryotes), and also regulate bacterial community size (for instance during bacterial blooms). As genetic entities, phages are submitted to mutations and natural selection, which changes their DNA sequence. Therefore, comparative genomic analyses of contemporary phages can be useful to understand their evolutionary dynamics. International initiatives such as SEA-PHAGES have started to tackle the issue of history of phage-bacteria interactions and to describe the dynamics of the co-evolution between bacterial hosts and their associated viruses. Indeed, the understanding of this cross-talk has many potential implications in terms of health and agriculture, among others. The work of Koert et al. (2021) deals with one of the largest groups of bacteria (Actinobacteria), which are Gram-positive bacteria mainly found in soil and water. Some soil-born Actinobacteria develop filamentous structures reminiscent of the mycelium of eukaryotic fungi. In this study, the authors focused on the Streptomyces clade, a large genus of Actinobacteria colonized by phages known for their high level of genetic diversity. The authors tested the hypothesis that large exchanges of genetic material occurred between Streptomyces and diverse phages associated with bacterial hosts. Using public datasets, their comparative phylogenomic analyses identified a new cluster among Actinobacteria–infecting phages closely related to phages of Firmicutes. Moreover, the GC content and codon-usage biases of this group of phages of Actinobacteria are similar to those of Firmicutes. This work demonstrates for the first time the transfer of a bacteriophage lineage from one bacterial phylum to another one. The results presented here suggest that the age of the described transfer is probably recent since several genomic characteristics of the phage are not fully adapted to their new hosts. However, the frequency of such transfer events remains an open question. If frequent, such exchanges would mean that pools of bacteriophages are regularly fueled by genetic material coming from external sources, which would have important implications for the co-evolutionary dynamics of phages and bacteria. References Koert, M., López-Pérez, J., Courtney Mattson, C., Caruso, S. and Erill, I. (2021) Evidence for shared ancestry between Actinobacteria and Firmicutes bacteriophages. bioRxiv, 842583, version 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Genomics. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/842583 | Evidence for shared ancestry between Actinobacteria and Firmicutes bacteriophages | Matthew Koert, Júlia López-Pérez, Courtney Mattson, Steven M. Caruso, Ivan Erill | <p>Bacteriophages typically infect a small set of related bacterial strains. The transfer of bacteriophages between more distant clades of bacteria has often been postulated, but remains mostly unaddressed. In this work we leverage the sequencing ... |  | Evolutionary genomics | Denis Tagu | 2019-12-10 15:26:31 | View | |

07 Aug 2023

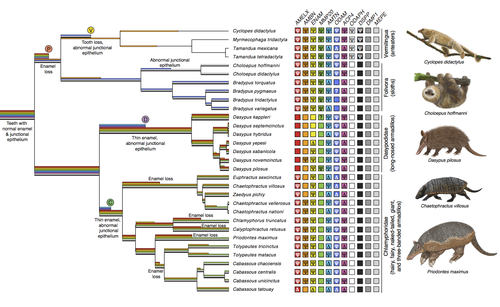

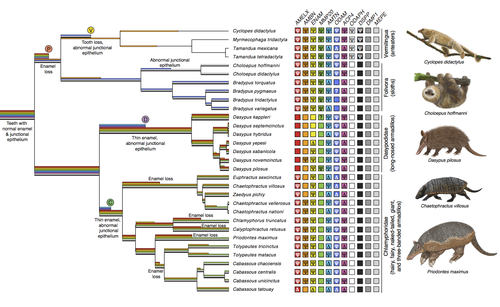

Genomic data suggest parallel dental vestigialization within the xenarthran radiationChristopher A Emerling, Gillian C Gibb, Marie-Ka Tilak, Jonathan J Hughes, Melanie Kuch, Ana T Duggan, Hendrik N Poinar, Michael W Nachman, Frederic Delsuc https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.09.519446What does dental gene decay tell us about the regressive evolution of teeth in South American mammals?Recommended by Didier Casane based on reviews by Juan C. Opazo, Régis Debruyne and Nicolas PolletA group of mammals, Xenathra, evolved and diversified in South America during its long period of isolation in the early to mid Cenozoic era. More recently, as a result of the Great Faunal Interchange between South America and North America, many xenarthran species went extinct. The thirty-one extant species belong to three groups: armadillos, sloths and anteaters. They share dental degeneration. However, the level of degeneration is variable. Anteaters entirely lack teeth, sloths have intermediately regressed teeth and most armadillos have a toothless premaxilla, as well as peg-like, single-rooted teeth that lack enamel in adult animals (Vizcaíno 2009). This diversity raises a number of questions about the evolution of dentition in these mammals. Unfortunately, the fossil record is too poor to provide refined information on the different stages of regressive evolution in these clades. In such cases, the identification of loss-of-function mutations and/or relaxed selection in genes related to a character regression can be very informative (Emerling and Springer 2014; Meredith et al. 2014; Policarpo et al. 2021). Indeed, shared and unique pseudogenes/relaxed selection can tell us to what extent regression has occurred in common ancestors and whether some changes are lineage-specific. In addition, the distribution of pseudogenes/relaxed selection on the branches of a phylogenetic tree is related to the evolutionary processes involved. A much higher density of pseudogenes in the most internal branches indicates that degeneration took place early and over a short period of time, consistent with selection against the presence of the morphological character with which they are associated, while pseudogenes distributed evenly in many internal and external branches suggest a more gradual process over many millions of years, in line with relaxed selection and fixation of loss-of-function mutations by genetic drift. In this paper (Emerling et al. 2023), the authors examined the dynamics of decay of 11 dental genes that may parallel teeth regression. The analyses of the data reported in this paper clearly point to xenarthran teeth having repeatedly regressed in parallel in the three clades. In fact, no loss-of-function mutation is shared by all species examined. However, more genes should be studied to confirm the hypothesis that the common ancestor of extant xenarthrans had normal dentition. There are distinct patterns of gene loss in different lineages that are associated with the variation in dentition observed across the clades. These patterns of gene loss suggest that regressive evolution took place both gradually and in relatively rapid, discrete phases during the diversification of xenarthrans. This study underscores the utility of using pseudogenes to reconstruct evolutionary history of morphological characters when fossils are sparse. References Emerling CA, Gibb GC, Tilak M-K, Hughes JJ, Kuch M, Duggan AT, Poinar HN, Nachman MW, Delsuc F. 2023. Genomic data suggest parallel dental vestigialization within the xenarthran radiation. bioRxiv, 2022.12.09.519446, ver 2, peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.09.519446 Emerling CA, Springer MS. 2014. Eyes underground: Regression of visual protein networks in subterranean mammals. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 78: 260-270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2014.05.016 Meredith RW, Zhang G, Gilbert MTP, Jarvis ED, Springer MS. 2014. Evidence for a single loss of mineralized teeth in the common avian ancestor. Science 346: 1254390. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1254390 Policarpo M, Fumey J, Lafargeas P, Naquin D, Thermes C, Naville M, Dechaud C, Volff J-N, Cabau C, Klopp C, et al. 2021. Contrasting gene decay in subterranean vertebrates: insights from cavefishes and fossorial mammals. Molecular Biology and Evolution 38: 589-605. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msaa249 Vizcaíno SF. 2009. The teeth of the “toothless”: novelties and key innovations in the evolution of xenarthrans (Mammalia, Xenarthra). Paleobiology 35: 343-366. https://doi.org/10.1666/0094-8373-35.3.343 | Genomic data suggest parallel dental vestigialization within the xenarthran radiation | Christopher A Emerling, Gillian C Gibb, Marie-Ka Tilak, Jonathan J Hughes, Melanie Kuch, Ana T Duggan, Hendrik N Poinar, Michael W Nachman, Frederic Delsuc | <p style="text-align: justify;">The recent influx of genomic data has provided greater insights into the molecular basis for regressive evolution, or vestigialization, through gene loss and pseudogenization. As such, the analysis of gene degradati... |  | Evolutionary genomics, Vertebrates | Didier Casane | 2022-12-12 16:01:57 | View | |

24 Jan 2024

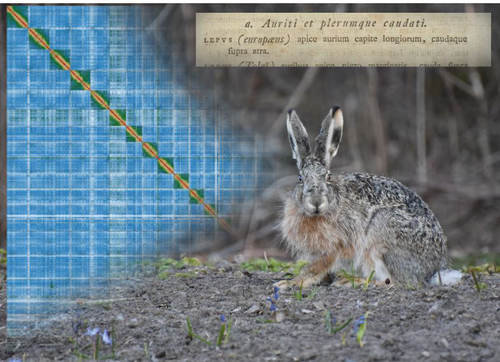

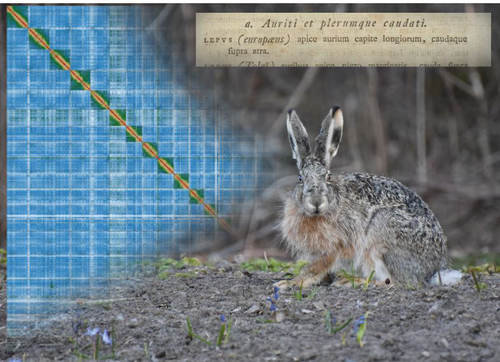

High quality genome assembly of the brown hare (Lepus europaeus) with chromosome-level scaffoldingCraig Michell, Joanna Collins, Pia K. Laine, Zsofia Fekete, Riikka Tapanainen, Jonathan M. D. Wood, Steffi Goffart, Jaakko L. O. Pohjoismaki https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.29.555262A high quality reference genome of the brown hareRecommended by Ed Hollox based on reviews by Merce Montoliu-Nerin and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Merce Montoliu-Nerin and 1 anonymous reviewer

The brown hare, or European hare, Lupus europaeus, is a widespread mammal whose natural range spans western Eurasia. At the northern limit of its range, it hybridises with the mountain hare (L. timidis), and humans have introduced it into other continents. It represents a particularly interesting mammal to study for its population genetics, extensive hybridisation zones, and as an invasive species. This study (Michell et al. 2024) has generated a high-quality assembly of a genome from a brown hare from Finland using long PacBio HiFi sequencing reads and Hi-C scaffolding. The contig N50 of this new genome is 43 Mb, and completeness, assessed using BUSCO, is 96.1%. The assembly comprises 23 autosomes, and an X chromosome and Y chromosome, with many chromosomes including telomeric repeats, indicating the high level of completeness of this assembly. While the genome of the mountain hare has previously been assembled, its assembly was based on a short-read shotgun assembly, with the rabbit as a reference genome. The new high-quality brown hare genome assembly allows a direct comparison with the rabbit genome assembly. For example, the assembly addresses the karyotype difference between the hare (n=24) and the rabbit (n=22). Chromosomes 12 and 17 of the hare are equivalent to chromosome 1 of the rabbit, and chromosomes 13 and 16 of the hare are equivalent to chromosome 2 of the rabbit. The new assembly also provides a hare Y-chromosome, as the previous mountain hare genome was from a female. This new genome assembly provides an important foundation for population genetics and evolutionary studies of lagomorphs. References Michell, C., Collins, J., Laine, P. K., Fekete, Z., Tapanainen, R., Wood, J. M. D., Goffart, S., Pohjoismäki, J. L. O. (2024). High quality genome assembly of the brown hare (Lepus europaeus) with chromosome-level scaffolding. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.29.555262 | High quality genome assembly of the brown hare (*Lepus europaeus*) with chromosome-level scaffolding | Craig Michell, Joanna Collins, Pia K. Laine, Zsofia Fekete, Riikka Tapanainen, Jonathan M. D. Wood, Steffi Goffart, Jaakko L. O. Pohjoismaki | <p style="text-align: justify;">We present here a high-quality genome assembly of the brown hare (Lepus europaeus Pallas), based on a fibroblast cell line of a male specimen from Liperi, Eastern Finland. This brown hare genome represents the first... |  | ERGA Pilot, Vertebrates | Ed Hollox | 2023-10-16 20:46:39 | View | |

06 Jul 2021

A pipeline to detect the relationship between transposable elements and adjacent genes in host genomesCaroline Meguerditchian, Ayse Ergun, Veronique Decroocq, Marie Lefebvre, Quynh-Trang Bui https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.25.432867A new tool to cross and analyze TE and gene annotationsRecommended by Emmanuelle Lerat based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersTransposable elements (TEs) are important components of genomes. Indeed, they are now recognized as having a major role in gene and genome evolution (Biémont 2010). In particular, several examples have shown that the presence of TEs near genes may influence their functioning, either by recruiting particular epigenetic modifications (Guio et al. 2018) or by directly providing new regulatory sequences allowing new expression patterns (Chung et al. 2007; Sundaram et al. 2014). Therefore, the study of the interaction between TEs and their host genome requires tools to easily cross-annotate both types of entities. In particular, one needs to be able to identify all TEs located in the close vicinity of genes or inside them. Such task may not always be obvious for many biologists, as it requires informatics knowledge to develop their own script codes. In their work, Meguerdichian et al. (2021) propose a command-line pipeline that takes as input the annotations of both genes and TEs for a given genome, then detects and reports the positional relationships between each TE insertion and their closest genes. The results are processed into an R script to provide tables displaying some statistics and graphs to visualize these relationships. This tool has the potential to be very useful for performing preliminary analyses before studying the impact of TEs on gene functioning, especially for biologists. Indeed, it makes it possible to identify genes close to TE insertions. These identified genes could then be specifically considered in order to study in more detail the link between the presence of TEs and their functioning. For example, the identification of TEs close to genes may allow to determine their potential role on gene expression. References Biémont C (2010). A brief history of the status of transposable elements: from junk DNA to major players in evolution. Genetics, 186, 1085–1093. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.110.124180 Chung H, Bogwitz MR, McCart C, Andrianopoulos A, ffrench-Constant RH, Batterham P, Daborn PJ (2007). Cis-regulatory elements in the Accord retrotransposon result in tissue-specific expression of the Drosophila melanogaster insecticide resistance gene Cyp6g1. Genetics, 175, 1071–1077. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.106.066597 Guio L, Vieira C, González J (2018). Stress affects the epigenetic marks added by natural transposable element insertions in Drosophila melanogaster. Scientific Reports, 8, 12197. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-30491-w Meguerditchian C, Ergun A, Decroocq V, Lefebvre M, Bui Q-T (2021). A pipeline to detect the relationship between transposable elements and adjacent genes in host genomes. bioRxiv, 2021.02.25.432867, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.25.432867 Sundaram V, Cheng Y, Ma Z, Li D, Xing X, Edge P, Snyder MP, Wang T (2014). Widespread contribution of transposable elements to the innovation of gene regulatory networks. Genome Research, 24, 1963–1976. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.168872.113 | A pipeline to detect the relationship between transposable elements and adjacent genes in host genomes | Caroline Meguerditchian, Ayse Ergun, Veronique Decroocq, Marie Lefebvre, Quynh-Trang Bui | <p>Understanding the relationship between transposable elements (TEs) and their closest positional genes in the host genome is a key point to explore their potential role in genome evolution. Transposable elements can regulate and affect gene expr... |  | Bioinformatics, Viruses and transposable elements | Emmanuelle Lerat | 2021-03-03 15:08:34 | View | |

11 Sep 2023

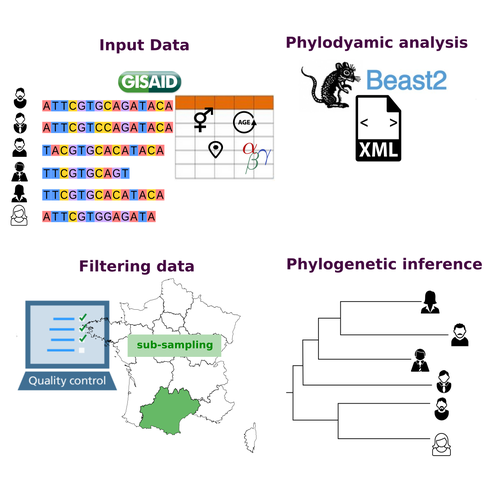

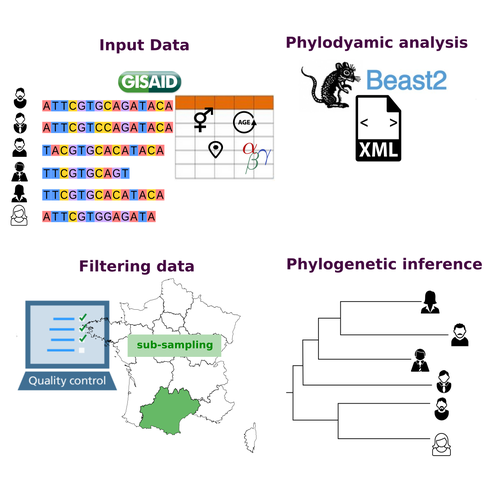

COVFlow: phylodynamics analyses of viruses from selected SARS-CoV-2 genome sequencesGonché Danesh, Corentin Boennec, Laura Verdurme, Mathilde Roussel, Sabine Trombert-Paolantoni, Benoit Visseaux, Stephanie Haim-Boukobza, Samuel Alizon https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.17.496544A pipeline to select SARS-CoV-2 sequences for reliable phylodynamic analysesRecommended by Emmanuelle Lerat based on reviews by Gabriel Wallau and Bastien BoussauPhylodynamic approaches enable viral genetic variation to be tracked over time, providing insight into pathogen phylogenetic relationships and epidemiological dynamics. These are important methods for monitoring viral spread, and identifying important parameters such as transmission rate, geographic origin and duration of infection [1]. This knowledge makes it possible to adjust public health measures in real-time and was important in the case of the COVID-19 pandemic [2]. However, these approaches can be complicated to use when combining a very large number of sequences. This was particularly true during the COVID-19 pandemic, when sequencing data representing millions of entire viral genomes was generated, with associated metadata enabling their precise identification. Danesh et al. [3] present a bioinformatics pipeline, CovFlow, for selecting relevant sequences according to user-defined criteria to produce files that can be used directly for phylodynamic analyses. The selection of sequences first involves a quality filter on the size of the sequences and the absence of unresolved bases before being able to make choices based on the associated metadata. Once the sequences are selected, they are aligned and a time-scaled phylogenetic tree is inferred. An output file in a format directly usable by BEAST 2 [4] is finally generated. To illustrate the use of the pipeline, Danesh et al. [3] present an analysis of the Delta variant in two regions of France. They observed a delay in the start of the epidemic depending on the region. In addition, they identified genetic variation linked to the start of the school year and the extension of vaccination, as well as the arrival of a new variant. This tool will be of major interest to researchers analysing SARS-CoV-2 sequencing data, and a number of future developments are planned by the authors. References [1] Baele G, Dellicour S, Suchard MA, Lemey P, Vrancken B. 2018. Recent advances in computational phylodynamics. Curr Opin Virol. 31:24-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coviro.2018.08.009 [2] Attwood SW, Hill SC, Aanensen DM, Connor TR, Pybus OG. 2022. Phylogenetic and phylodynamic approaches to understanding and combating the early SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Nat Rev Genet. 23:547-562. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-022-00483-8 [3] Danesh G, Boennec C, Verdurme L, Roussel M, Trombert-Paolantoni S, Visseaux B, Haim-Boukobza S, Alizon S. 2023. COVFlow: phylodynamics analyses of viruses from selected SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences. bioRxiv, ver. 7 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.17.496544 [4] Bouckaert R, Heled J, Kühnert D, Vaughan T, Wu C-H et al. 2014. BEAST 2: a software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLoS Comput Biol 10: e1003537. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003537 | COVFlow: phylodynamics analyses of viruses from selected SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences | Gonché Danesh, Corentin Boennec, Laura Verdurme, Mathilde Roussel, Sabine Trombert-Paolantoni, Benoit Visseaux, Stephanie Haim-Boukobza, Samuel Alizon | <p style="text-align: justify;">Phylodynamic analyses generate important and timely data to optimise public health response to SARS-CoV-2 outbreaks and epidemics. However, their implementation is hampered by the massive amount of sequence data and... |  | Bioinformatics, Evolutionary genomics | Emmanuelle Lerat | 2022-12-12 09:04:01 | View |