Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * ▲ | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

06 May 2022

A deep dive into genome assemblies of non-vertebrate animalsNadège Guiglielmoni, Ramón Rivera-Vicéns, Romain Koszul, Jean-François Flot https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202111.0170.v3Diving, and even digging, into the wild jungle of annotation pathways for non-vertebrate animalsRecommended by Francois Sabot based on reviews by Yann Bourgeois, Cécile Monat, Valentina Peona and Benjamin Istace based on reviews by Yann Bourgeois, Cécile Monat, Valentina Peona and Benjamin Istace

In their paper, Guiglielmoni et al. propose we pick up our snorkels and palms and take "A deep dive into genome assemblies of non-vertebrate animals" (1). Indeed, while numerous assembly-related tools were developed and tested for human genomes (or at least vertebrates such as mice), very few were tested on non-vertebrate animals so far. Moreover, most of the benchmarks are aimed at raw assembly tools, and very few offer a guide from raw reads to an almost finished assembly, including quality control and phasing. This huge and exhaustive review starts with an overview of the current sequencing technologies, followed by the theory of the different approaches for assembly and their implementation. For each approach, the authors present some of the most representative tools, as well as the limits of the approach. The authors additionally present all the steps required to obtain an almost complete assembly at a chromosome-scale, with all the different technologies currently available for scaffolding, QC, and phasing, and the way these tools can be applied to non-vertebrates animals. Finally, they propose some useful advice on the choice of the different approaches (but not always tools, see below), and advocate for a robust genome database with all information on the way the assembly was obtained. This review is a very complete one for now and is a very good starting point for any student or scientist interested to start working on genome assembly, from either model or non-model organisms. However, the authors do not provide a list of tools or a benchmark of them as a recommendation. Why? Because such a proposal may be obsolete in less than a year.... Indeed, with the explosion of the 3rd generation of sequencing technology, assembly tools (from different steps) are constantly evolving, and their relative performance increases on a monthly basis. In addition, some tools are really efficient at the time of a review or of an article, but are not further developed later on, and thus will not evolve with the technology. We have all seen it with wonderful tools such as Chiron (2) or TopHat (3), which were very promising ones, but cannot be developed further due to the stop of the project, the end of the contract of the post-doc in charge of the development, or the decision of the developer to switch to another paradigm. Such advice would, therefore, need to be constantly updated. Thus, the manuscript from Guiglielmoni et al will be an almost intemporal one (up to the next sequencing revolution at last), and as they advocated for a more informed genome database, I think we should consider a rolling benchmarking system (tools, genome and sequence dataset) allowing to keep the performance of the tools up-to-date, and to propose the best set of assembly tools for a given type of genome. References 1. Guiglielmoni N, Rivera-Vicéns R, Koszul R, Flot J-F (2022) A Deep Dive into Genome Assemblies of Non-vertebrate Animals. Preprints, 2021110170, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202111.0170 2. Teng H, Cao MD, Hall MB, Duarte T, Wang S, Coin LJM (2018) Chiron: translating nanopore raw signal directly into nucleotide sequence using deep learning. GigaScience, 7, giy037. https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giy037 3. Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzberg SL (2009) TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics, 25, 1105–1111. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp120 | A deep dive into genome assemblies of non-vertebrate animals | Nadège Guiglielmoni, Ramón Rivera-Vicéns, Romain Koszul, Jean-François Flot | <p style="text-align: justify;">Non-vertebrate species represent about ∼95% of known metazoan (animal) diversity. They remain to this day relatively unexplored genetically, but understanding their genome structure and function is pivotal for expan... |  | Bioinformatics, Evolutionary genomics | Francois Sabot | Valentina Peona, Benjamin Istace, Cécile Monat, Yann Bourgeois | 2021-11-10 17:47:31 | View |

24 Feb 2023

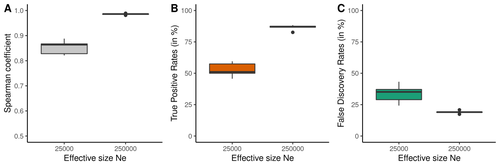

Performance and limitations of linkage-disequilibrium-based methods for inferring the genomic landscape of recombination and detecting hotspots: a simulation studyMarie Raynaud, Pierre-Alexandre Gagnaire, Nicolas Galtier https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.30.486352How to interpret the inference of recombination landscapes on methods based on linkage disequilibrium?Recommended by Sebastian Ernesto Ramos-Onsins based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Data interpretation depends on previously established and validated tools, designed for a specific type of data. These methods, however, are usually based on simple models with validity subject to a set of theoretical parameterized conditions and data types. Accordingly, the tool developers provide the potential users with guidelines for data interpretations within the tools’ limitation. Nevertheless, once the methodology is accepted by the community, it is employed in a large variety of empirical studies outside of the method’s original scope or that typically depart from the standard models used for its design, thus potentially leading to the wrong interpretation of the results. Numerous empirical studies inferred recombination rates across genomes, detecting hotspots of recombination and comparing related species (e.g., Shanfelter et al. 2019, Spence and Song 2019). These studies used indirect methodologies based on the signals that recombination left in the genome, such as linkage disequilibrium and the patterns of haplotype segregation (e.g.,Chan et al. 2012). The conclusions from these analyses have been used, for example, to interpret the evolution of the chromosomal structure or the evolution of recombination among closely related species. Indirect methods have the advantage of collecting a large quantity of recombination events, and thus have a better resolution than direct methods (which only detect the few recombination events occurring at that time). On the other hand, indirect methods are affected by many different evolutionary events, such as demographic changes and selection. Indeed, the inference of recombination levels across the genome has not been studied accurately in non-standard conditions. Linkage disequilibrium is affected by several factors that can modify the recombination inference, such as demographic history, events of selection, population size, and mutation rate, but is also related to the size of the studied sample, and other technical parameters defined for each specific methodology. Raynaud et al (2023) analyzed the reliability of the recombination rate inference when considering the violation of several standard assumptions (evolutionary and methodological) in one of the most popular families of methods based on LDhat (McVean et al. 2004), specifically its improved version, LDhelmet (Chan et al. 2012). These methods cover around 70 % of the studies that infer recombination rates. The authors used recombination maps, obtained from empirical studies on humans, and included hotspots, to perform a detailed simulation study of the capacity of this methodology to correctly infer the pattern of recombination and the location of these hotspots. Correlations between the real, and inferred values from simulations were obtained, as well as several rates, such as the true positive and false discovery rate to detect hotspots. The authors of this work send a message of caution to researchers that are applying this methodology to interpret data from the inference of recombination landscapes and the location of hotspots. The inference of recombination landscapes and hotspots can differ considerably even in standard model conditions. In addition, demographic processes, like bottleneck or admixture, but also the level of population size and mutation rates, can substantially affect the estimation accuracy of the level of recombination and the location of hotspots. Indeed, the inference of the location of hotspots in simulated data with the same landscape, can be very imprecise when standard assumptions are violated or not considered. These effects may lead to incorrect interpretations, for example about the conservation of recombination maps between closely related species. Finally, Raynaud et al (2023) included a useful guide with advice on how to obtain accurate recombination estimations with methods based on linkage disequilibrium, also emphasizing the limitations of such approaches. REFERENCES Chan AH, Jenkins PA, Song YS (2012) Genome-Wide Fine-Scale Recombination Rate Variation in Drosophila melanogaster. PLOS Genetics, 8, e1003090. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003090 McVean GAT, Myers SR, Hunt S, Deloukas P, Bentley DR, Donnelly P (2004) The Fine-Scale Structure of Recombination Rate Variation in the Human Genome. Science, 304, 581–584. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1092500 Raynaud M, Gagnaire P-A, Galtier N (2023) Performance and limitations of linkage-disequilibrium-based methods for inferring the genomic landscape of recombination and detecting hotspots: a simulation study. bioRxiv, 2022.03.30.486352, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.30.486352 Spence JP, Song YS (2019) Inference and analysis of population-specific fine-scale recombination maps across 26 diverse human populations. Science Advances, 5, eaaw9206. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aaw9206 | Performance and limitations of linkage-disequilibrium-based methods for inferring the genomic landscape of recombination and detecting hotspots: a simulation study | Marie Raynaud, Pierre-Alexandre Gagnaire, Nicolas Galtier | <p style="text-align: justify;">Knowledge of recombination rate variation along the genome provides important insights into genome and phenotypic evolution. Population genomic approaches offer an attractive way to infer the population-scaled recom... |  | Bioinformatics, Evolutionary genomics, Population genomics | Sebastian Ernesto Ramos-Onsins | 2022-04-05 14:59:14 | View | |

24 Feb 2023

MacSyFinder v2: Improved modelling and search engine to identify molecular systems in genomesBertrand Néron, Rémi Denise, Charles Coluzzi, Marie Touchon, Eduardo P. C. Rocha, Sophie S. Abby https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.02.506364A unique and customizable approach for functionally annotating prokaryotic genomesRecommended by Gavin Douglas based on reviews by Kwee Boon Brandon Seah and Max Emil Schön based on reviews by Kwee Boon Brandon Seah and Max Emil Schön

Macromolecular System Finder (MacSyFinder) v2 (Néron et al., 2023) is a newly updated approach for performing functional annotation of prokaryotic genomes (Abby et al., 2014). This tool parses an input file of protein sequences from a single genome (either ordered by genome location or unordered) and identifies the presence of specific cellular functions (referred to as “systems”). These systems are called based on two criteria: (1) that the "quorum" of a minimum set of core proteins involved is reached the “quorum” of a minimum set of core proteins being involved that are present, and (2) that the genes encoding these proteins are in the expected genomic organization (e.g., within the same order in an operon), when ordered data is provided. I believe the MacSyFinder approach represents an improvement over more commonly used methods exactly because it can incorporate such information on genomic organization, and also because it is more customizable. Before properly appreciating these points, it is worth noting the norms and key challenges surrounding high-throughput functional annotation of prokaryotic genomes. Genome sequences are being added to online repositories at increasing rates, which has led to an enormous amount of bacterial genome diversity available to investigate (Altermann et al., 2022). A key aspect of understanding this diversity is the functional annotation step, which enables genes to be grouped into more biologically interpretable categories. For instance, gene calls can be mapped against existing Clusters of Orthologous Genes, which are themselves grouped into general categories such as ‘Transcription’ and ‘Lipid metabolism’ (Galperin et al., 2021). This approach is valuable but is primarily used for global summaries of functional annotations within a genome: for example, it could be useful to know that a genome is particularly enriched for genes involved in lipid metabolism. However, knowing that a particular gene is involved in the general process of lipid metabolism is less likely to be actionable. In other words, the desired specificity of a gene’s functional annotation will depend on the exact question being investigated. There is no shortage of functional ontologies in genomics that can be applied for this purpose (Douglas and Langille, 2021), and researchers are often overwhelmed by the choice of which functional ontology to use. In this context, giving researchers the ability to precisely specify the gene families and operon structures they are interested in identifying across genomes provides useful control over what precise functions they are profiling. Of course, most researchers will lack the information and/or expertise to fully take advantage of MacSyFinder’s customizable features, but having this option for specialized purposes is valuable. The other MacSyFinder feature that I find especially noteworthy is that it can incorporate genomic organization (e.g., of genes ordered in operons) when calling systems. This is a rare feature among commonly used tools for functional annotation and likely results in much higher specificity. As the authors note, this capability makes the co-occurrence of paralogs, and other divergent genes that share sequence similarity, to contribute less noise (i.e., they result in fewer false positive calls). It is important to emphasize that these features are not new additions in MacSyFinder v2, but there are many other valuable changes. Most practically, this release is written in Python 3, rather than the obsolete Python 2.7, and was made more computationally efficient, which will enable MacSyFinder to be more widely used and more easily maintained moving forward. In addition, the search algorithm for analyzing individual proteins was fundamentally updated as well. The authors show that their improvements to the search algorithm result in an 8% and 20% increase in the number of identified calls for single and multi-locus secretion systems, respectively. Taken together, MacSyFinder v2 represents both practical and scientific improvements over the previous version, which will be of great value to the field. References Abby SS, Néron B, Ménager H, Touchon M, Rocha EPC (2014) MacSyFinder: A Program to Mine Genomes for Molecular Systems with an Application to CRISPR-Cas Systems. PLOS ONE, 9, e110726. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0110726 Altermann E, Tegetmeyer HE, Chanyi RM (2022) The evolution of bacterial genome assemblies - where do we need to go next? Microbiome Research Reports, 1, 15. https://doi.org/10.20517/mrr.2022.02 Douglas GM, Langille MGI (2021) A primer and discussion on DNA-based microbiome data and related bioinformatics analyses. Peer Community Journal, 1. https://doi.org/10.24072/pcjournal.2 Galperin MY, Wolf YI, Makarova KS, Vera Alvarez R, Landsman D, Koonin EV (2021) COG database update: focus on microbial diversity, model organisms, and widespread pathogens. Nucleic Acids Research, 49, D274–D281. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa1018 Néron B, Denise R, Coluzzi C, Touchon M, Rocha EPC, Abby SS (2023) MacSyFinder v2: Improved modelling and search engine to identify molecular systems in genomes. bioRxiv, 2022.09.02.506364, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.02.506364 | MacSyFinder v2: Improved modelling and search engine to identify molecular systems in genomes | Bertrand Néron, Rémi Denise, Charles Coluzzi, Marie Touchon, Eduardo P. C. Rocha, Sophie S. Abby | <p style="text-align: justify;">Complex cellular functions are usually encoded by a set of genes in one or a few organized genetic loci in microbial genomes. Macromolecular System Finder (MacSyFinder) is a program that uses these properties to mod... |  | Bacteria and archaea, Bioinformatics, Functional genomics | Gavin Douglas | Kwee Boon Brandon Seah, Max Emil Schön | 2022-09-09 10:30:31 | View |

23 Mar 2022

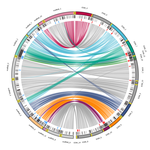

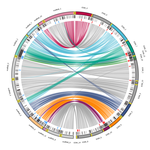

Chromosomal rearrangements with stable repertoires of genes and transposable elements in an invasive forest-pathogenic fungusArthur Demene, Benoit Laurent, Sandrine Cros-Arteil, Christophe Boury, Cyril Dutech https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.09.434572Comparative genomics in the chestnut blight fungus Cryphonectria parasitica reveals large chromosomal rearrangements and a stable genome organizationRecommended by Sebastien Duplessis based on reviews by Benjamin Schwessinger and 1 anonymous reviewerAbout twenty-five years after the sequencing of the first fungal genome and a dozen years after the first plant pathogenic fungi genomes were sequenced, unprecedented international efforts have led to an impressive collection of genomes available for the community of mycologists in international databases (Goffeau et al. 1996, Dean et al. 2005; Spatafora et al. 2017). For instance, to date, the Joint Genome Institute Mycocosm database has collected more than 2,100 fungal genomes over the fungal tree of life (https://mycocosm.jgi.doe.gov). Such resources are paving the way for comparative genomics, population genomics and phylogenomics to address a large panel of questions regarding the biology and the ecology of fungal species. Early on, population genomics applied to pathogenic fungi revealed a great diversity of genome content and organization and a wide variety of variants and rearrangements (Raffaele and Kamoun 2012, Hartmann 2022). Such plasticity raises questions about how to choose a representative genome to serve as an ideal reference to address pertinent biological questions. Cryphonectria parasitica is a fungal pathogen that is infamous for the devastation of chestnut forests in North America after its accidental introduction more than a century ago (Anagnostakis 1987). Since then, it has been a quarantine species under surveillance in various parts of the world. As for other fungi causing diseases on forest trees, the study of adaptation to its host in the forest ecosystem and of its reproduction and dissemination modes is more complex than for crop-targeting pathogens. A first reference genome was published in 2020 for the chestnut blight fungus C. parasitica strain EP155 in the frame of an international project with the DOE JGI (Crouch et al. 2020). Another genome was then sequenced from the French isolate YVO003, which showed a few differences in the assembly suggesting possible rearrangements (Demené et al. 2019). Here the sequencing of a third isolate ESM015 from the native area of C. parasitica in Japan allows to draw broader comparative analysis and particularly to compare between native and introduced isolates (Demené et al. 2022). Demené and collaborators report on a new genome sequence using up-to-date long-read sequencing technologies and they provide an improved genome assembly. Comparison with previously published C. parasitica genomes did not reveal dramatic changes in the overall chromosomal landscapes, but large rearrangements could be spotted. Despite these rearrangements, the genome content and organization – i.e. genes and repeats – remain stable, with a limited number of genes gains and losses. As in any fungal plant pathogen genome, the repertoire of candidate effectors predicted among secreted proteins was more particularly scrutinized. Such effector genes have previously been reported in other pathogens in repeat-enriched plastic genomic regions with accelerated evolutionary rates under the pressure of the host immune system (Raffaele and Kamoun 2012). Demené and collaborators established a list of priority candidate effectors in the C. parasitica gene catalog likely involved in the interaction with the host plant which will require more attention in future functional studies. Six major inter-chromosomal translocations were detected and are likely associated with double break strands repairs. The authors speculate on the possible effects that these translocations may have on gene organization and expression regulation leading to dramatic phenotypic changes in relation to introduction and invasion in new continents and the impact regarding sexual reproduction in this fungus (Demené et al. 2022). I recommend this article not only because it is providing an improved assembly of a reference genome for C. parasitica, but also because it adds diversity in terms of genome references availability, with a third high-quality assembly. Such an effort in the tree pathology community for a pathogen under surveillance is of particular importance for future progress in post-genomic analysis, e.g. in further genomic population studies (Hartmann 2022). References Anagnostakis SL (1987) Chestnut Blight: The Classical Problem of an Introduced Pathogen. Mycologia, 79, 23–37. https://doi.org/10.2307/3807741 Crouch JA, Dawe A, Aerts A, Barry K, Churchill ACL, Grimwood J, Hillman BI, Milgroom MG, Pangilinan J, Smith M, Salamov A, Schmutz J, Yadav JS, Grigoriev IV, Nuss DL (2020) Genome Sequence of the Chestnut Blight Fungus Cryphonectria parasitica EP155: A Fundamental Resource for an Archetypical Invasive Plant Pathogen. Phytopathology®, 110, 1180–1188. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-12-19-0478-A Dean RA, Talbot NJ, Ebbole DJ, Farman ML, Mitchell TK, Orbach MJ, Thon M, Kulkarni R, Xu J-R, Pan H, Read ND, Lee Y-H, Carbone I, Brown D, Oh YY, Donofrio N, Jeong JS, Soanes DM, Djonovic S, Kolomiets E, Rehmeyer C, Li W, Harding M, Kim S, Lebrun M-H, Bohnert H, Coughlan S, Butler J, Calvo S, Ma L-J, Nicol R, Purcell S, Nusbaum C, Galagan JE, Birren BW (2005) The genome sequence of the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Nature, 434, 980–986. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03449 Demené A., Laurent B., Cros-Arteil S., Boury C. and Dutech C. 2022. Chromosomal rearrangements with stable repertoires of genes and transposable elements in an invasive forest-pathogenic fungus. bioRxiv, 2021.03.09.434572, ver.6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.09.434572 Goffeau A, Barrell BG, Bussey H, Davis RW, Dujon B, Feldmann H, Galibert F, Hoheisel JD, Jacq C, Johnston M, Louis EJ, Mewes HW, Murakami Y, Philippsen P, Tettelin H, Oliver SG (1996) Life with 6000 Genes. Science, 274, 546–567. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.274.5287.546 Hartmann FE (2022) Using structural variants to understand the ecological and evolutionary dynamics of fungal plant pathogens. New Phytologist, 234, 43–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.17907 Raffaele S, Kamoun S (2012) Genome evolution in filamentous plant pathogens: why bigger can be better. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 10, 417–430. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2790 Spatafora JW, Aime MC, Grigoriev IV, Martin F, Stajich JE, Blackwell M (2017) The Fungal Tree of Life: from Molecular Systematics to Genome-Scale Phylogenies. Microbiology Spectrum, 5, 5.5.03. https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.FUNK-0053-2016 | Chromosomal rearrangements with stable repertoires of genes and transposable elements in an invasive forest-pathogenic fungus | Arthur Demene, Benoit Laurent, Sandrine Cros-Arteil, Christophe Boury, Cyril Dutech | <p style="text-align: justify;">Chromosomal rearrangements have been largely described among eukaryotes, and may have important consequences on evolution of species. High genome plasticity has been often reported in Fungi, which may explain their ... |  | Evolutionary genomics, Fungi | Sebastien Duplessis | 2021-03-12 14:18:20 | View | |

11 Mar 2021

Gut microbial ecology of Xenopus tadpoles across life stagesThibault Scalvenzi, Isabelle Clavereau, Mickael Bourge, Nicolas Pollet https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.25.110734A comprehensive look at Xenopus gut microbiota: effects of feed, developmental stages and parental transmissionRecommended by Wirulda Pootakham based on reviews by Vanessa Marcelino and 1 anonymous reviewerIt is well established that the gut microbiota play an important role in the overall health of their hosts (Jandhyala et al. 2015). To date, there are still a limited number of studies on the complex microbial communites inhabiting vertebrate digestive systems, especially the ones that also explored the functional diversity of the microbial community (Bletz et al. 2016). This preprint by Scalvenzi et al. (2021) reports a comprehensive study on the phylogenetic and metabolic profiles of the Xenopus gut microbiota. The author describes significant changes in the gut microbiome communities at different developmental stages and demonstrates different microbial community composition across organs. In addition, the study also investigates the impact of diet on the Xenopus tadpole gut microbiome communities as well as how the bacterial communities are transmitted from parents to the next generation. This is one of the first studies that addresses the interactions between gut bacteria and tadpoles during the development. The authors observe the dynamics of gut microbiome communities during tadpole growth and metamorphosis. They also explore host-gut microbial community metabolic interactions and demostrate the capacity of the microbiome to complement the metabolic pathways of the Xenopus genome. Although this study is limited by the use of Xenopus tadpoles in a laboratory, which are probably different from those in nature, I believe it still provides important and valuable information for the research community working on vertebrate’s microbiota and their interaction with the host. References Bletz et al. (2016). Amphibian gut microbiota shifts differentially in community structure but converges on habitat-specific predicted functions. Nature Communications, 7(1), 1-12. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms13699 Jandhyala, S. M., Talukdar, R., Subramanyam, C., Vuyyuru, H., Sasikala, M., & Reddy, D. N. (2015). Role of the normal gut microbiota. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG, 21(29), 8787. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748%2Fwjg.v21.i29.8787 Scalvenzi, T., Clavereau, I., Bourge, M. & Pollet, N. (2021) Gut microbial ecology of Xenopus tadpoles across life stages. bioRxiv, 2020.05.25.110734, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Geonmics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.25.110734 | Gut microbial ecology of Xenopus tadpoles across life stages | Thibault Scalvenzi, Isabelle Clavereau, Mickael Bourge, Nicolas Pollet | <p><strong>Background</strong> The microorganism world living in amphibians is still largely under-represented and under-studied in the literature. Among anuran amphibians, African clawed frogs of the Xenopus genus stand as well-characterized mode... |  | Evolutionary genomics, Metagenomics, Vertebrates | Wirulda Pootakham | 2020-05-25 14:01:19 | View | |

01 Jul 2024

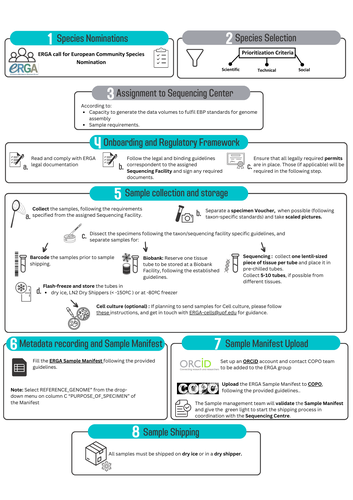

Contextualising samples: Supporting reference genomes of European biodiversity through sample and associated metadata collectionAstrid Böhne, Rosa Fernández, Jennifer A. Leonard, Ann M. McCartney, Seanna McTaggart, José Melo-Ferreira, Rita Monteiro, Rebekah A. Oomen, Olga Vinnere Pettersson, Torsten H. Struck https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.28.546652To avoid biases and to be FAIR, we need to CARE and share biodiversity metadataRecommended by Francois Sabot based on reviews by Julian Osuji and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Julian Osuji and 1 anonymous reviewer

Böhne et al. (2024) do not present a classical scientific paper per se but a report on how the European Reference Genome Atlas (ERGA) aims to deal with sampling and sample information, i.e. metadata. As the goal of ERGA is to provide an almost fully representative set of reference genomes representative of European biodiversity to serve many research areas in biology, they have to be really exhaustive. In this regard, in addition to providing sample metadata recording guidelines, they also discuss the biases existing in sampling and sequencing projects. The first task for such a project is to be sure that the data they generate will be usable and available in the future (“[in] perpetuity", Böhne et al. 2024). The authors deployed a very efficient pipeline for conserving information on sampling: location, physical information, copies of tissues and of DNA, shipping, legal/ethical aspects regarding the Nagoya Protocol, etc., alongside a best-practice manual. This effort is linked to practical guides for the DNA extraction of specific taxa. More generally, these details enable “Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable” (FAIR) principles (Wilkinson et al. 2016) to be followed. An important aspect of this paper, in addition to practical points, is the reflection upon the different biases inherent to the choice of sequenced samples. Acknowledging their own biases with regards to DNA extraction protocol efficiency, small genome size choice, as well as the availability of material (Nagoya Protocol aspects) and material transfer efficiency, the authors recommend in the future to not survey biodiversity by selecting one’s favorite samples or species, but also considering "orphan" taxa. Some of these "orphan" taxonomic groups belong to non-arthropod invertebrates but internal disparities are also prominent within other taxa. Finally, the implementation of the "Collective benefit, Authority to control, Responsibility, and Ethics" (CARE) principles (Carroll et al. 2021) will allow Indigenous rights to be considered when prioritizing samples, and to enable their "knowledge systems to permeate throughout the process of reference genome production and beyond" (Böhne et al. 2024). Last, but not least, as ERGA, including its Sampling and Sample Processing committee, is a large collective effort, it is very refreshing to read a paper starting with the acknowledgements and the roles of each member.

References Böhne A, Fernández R, Leonard JA, McCartney AM, McTaggart S, Melo-Ferreira J, Monteiro R, Oomen RA, Pettersson OV, Struck TH (2024) Contextualising samples: Supporting reference genomes of European biodiversity through sample and associated metadata collection. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.28.546652 Carroll SR, Herczog E, Hudson M, Russell K, Stall S (2021) Operationalizing the CARE and FAIR Principles for Indigenous data futures. Scientific Data, 8, 108. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-021-00892-0 Wilkinson MD, Dumontier M, Aalbersberg IjJ, Appleton G, Axton M, Baak A, Blomberg N, Boiten J-W, da Silva Santos LB, Bourne PE, Bouwman J, Brookes AJ, Clark T, Crosas M, Dillo I, Dumon O, Edmunds S, Evelo CT, Finkers R, Gonzalez-Beltran A, Gray AJG, Groth P, Goble C, Grethe JS, Heringa J, ’t Hoen PAC, Hooft R, Kuhn T, Kok R, Kok J, Lusher SJ, Martone ME, Mons A, Packer AL, Persson B, Rocca-Serra P, Roos M, van Schaik R, Sansone S-A, Schultes E, Sengstag T, Slater T, Strawn G, Swertz MA, Thompson M, van der Lei J, van Mulligen E, Velterop J, Waagmeester A, Wittenburg P, Wolstencroft K, Zhao J, Mons B (2016) The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data, 3, 160018. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18 | Contextualising samples: Supporting reference genomes of European biodiversity through sample and associated metadata collection | Astrid Böhne, Rosa Fernández, Jennifer A. Leonard, Ann M. McCartney, Seanna McTaggart, José Melo-Ferreira, Rita Monteiro, Rebekah A. Oomen, Olga Vinnere Pettersson, Torsten H. Struck | <p>The European Reference Genome Atlas (ERGA) consortium aims to generate a reference genome catalogue for all of Europe's eukaryotic biodiversity. The biological material underlying this mission, the specimens and their derived samples, are provi... |  | ERGA, ERGA BGE, ERGA Pilot, Evolutionary genomics | Francois Sabot | Julian Osuji, Francois Sabot, Anonymous | 2023-07-03 10:39:36 | View |

07 Aug 2023

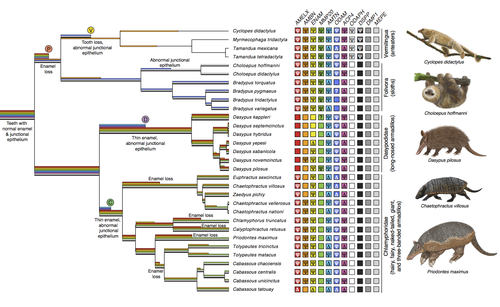

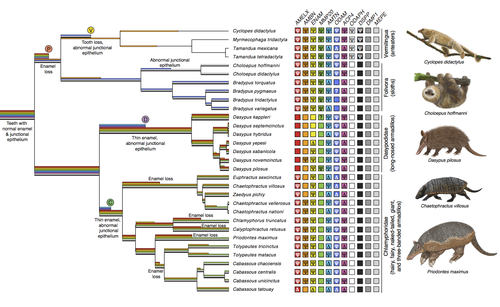

Genomic data suggest parallel dental vestigialization within the xenarthran radiationChristopher A Emerling, Gillian C Gibb, Marie-Ka Tilak, Jonathan J Hughes, Melanie Kuch, Ana T Duggan, Hendrik N Poinar, Michael W Nachman, Frederic Delsuc https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.09.519446What does dental gene decay tell us about the regressive evolution of teeth in South American mammals?Recommended by Didier Casane based on reviews by Juan C. Opazo, Régis Debruyne and Nicolas PolletA group of mammals, Xenathra, evolved and diversified in South America during its long period of isolation in the early to mid Cenozoic era. More recently, as a result of the Great Faunal Interchange between South America and North America, many xenarthran species went extinct. The thirty-one extant species belong to three groups: armadillos, sloths and anteaters. They share dental degeneration. However, the level of degeneration is variable. Anteaters entirely lack teeth, sloths have intermediately regressed teeth and most armadillos have a toothless premaxilla, as well as peg-like, single-rooted teeth that lack enamel in adult animals (Vizcaíno 2009). This diversity raises a number of questions about the evolution of dentition in these mammals. Unfortunately, the fossil record is too poor to provide refined information on the different stages of regressive evolution in these clades. In such cases, the identification of loss-of-function mutations and/or relaxed selection in genes related to a character regression can be very informative (Emerling and Springer 2014; Meredith et al. 2014; Policarpo et al. 2021). Indeed, shared and unique pseudogenes/relaxed selection can tell us to what extent regression has occurred in common ancestors and whether some changes are lineage-specific. In addition, the distribution of pseudogenes/relaxed selection on the branches of a phylogenetic tree is related to the evolutionary processes involved. A much higher density of pseudogenes in the most internal branches indicates that degeneration took place early and over a short period of time, consistent with selection against the presence of the morphological character with which they are associated, while pseudogenes distributed evenly in many internal and external branches suggest a more gradual process over many millions of years, in line with relaxed selection and fixation of loss-of-function mutations by genetic drift. In this paper (Emerling et al. 2023), the authors examined the dynamics of decay of 11 dental genes that may parallel teeth regression. The analyses of the data reported in this paper clearly point to xenarthran teeth having repeatedly regressed in parallel in the three clades. In fact, no loss-of-function mutation is shared by all species examined. However, more genes should be studied to confirm the hypothesis that the common ancestor of extant xenarthrans had normal dentition. There are distinct patterns of gene loss in different lineages that are associated with the variation in dentition observed across the clades. These patterns of gene loss suggest that regressive evolution took place both gradually and in relatively rapid, discrete phases during the diversification of xenarthrans. This study underscores the utility of using pseudogenes to reconstruct evolutionary history of morphological characters when fossils are sparse. References Emerling CA, Gibb GC, Tilak M-K, Hughes JJ, Kuch M, Duggan AT, Poinar HN, Nachman MW, Delsuc F. 2023. Genomic data suggest parallel dental vestigialization within the xenarthran radiation. bioRxiv, 2022.12.09.519446, ver 2, peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.09.519446 Emerling CA, Springer MS. 2014. Eyes underground: Regression of visual protein networks in subterranean mammals. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 78: 260-270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2014.05.016 Meredith RW, Zhang G, Gilbert MTP, Jarvis ED, Springer MS. 2014. Evidence for a single loss of mineralized teeth in the common avian ancestor. Science 346: 1254390. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1254390 Policarpo M, Fumey J, Lafargeas P, Naquin D, Thermes C, Naville M, Dechaud C, Volff J-N, Cabau C, Klopp C, et al. 2021. Contrasting gene decay in subterranean vertebrates: insights from cavefishes and fossorial mammals. Molecular Biology and Evolution 38: 589-605. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msaa249 Vizcaíno SF. 2009. The teeth of the “toothless”: novelties and key innovations in the evolution of xenarthrans (Mammalia, Xenarthra). Paleobiology 35: 343-366. https://doi.org/10.1666/0094-8373-35.3.343 | Genomic data suggest parallel dental vestigialization within the xenarthran radiation | Christopher A Emerling, Gillian C Gibb, Marie-Ka Tilak, Jonathan J Hughes, Melanie Kuch, Ana T Duggan, Hendrik N Poinar, Michael W Nachman, Frederic Delsuc | <p style="text-align: justify;">The recent influx of genomic data has provided greater insights into the molecular basis for regressive evolution, or vestigialization, through gene loss and pseudogenization. As such, the analysis of gene degradati... |  | Evolutionary genomics, Vertebrates | Didier Casane | 2022-12-12 16:01:57 | View | |

22 Nov 2023

The slow evolving genome of the xenacoelomorph worm Xenoturbella bockiPhilipp H. Schiffer, Paschalis Natsidis, Daniel J. Leite, Helen Robertson, François Lapraz, Ferdinand Marlétaz, Bastian Fromm, Liam Baudry, Fraser Simpson, Eirik Høye, Anne-C. Zakrzewski, Paschalia Kapli, Katharina J. Hoff, Steven Mueller, Martial Marbouty, Heather Marlow, Richard R. Copley, Romain Koszul, Peter Sarkies, Maximilian J. Telford https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.24.497508Genomic idiosyncrasies of Xenoturbella bocki: morphologically simple yet genetically complexRecommended by Rosa Fernandez based on reviews by Christopher Laumer and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Christopher Laumer and 1 anonymous reviewer

Xenoturbella is a genus of morphologically simple bilaterians inhabiting benthic environments. Until very recently, only one species was known from the genus, Xenoturbella bocki Westblad 1949 [1]. Less than a decade ago, five more species were discovered (X. churro, X. monstrosa, X. profunda, X. hollandorum [2] and X. japonica [3]). These enigmatic animals lack an anus, a coelom, reproductive organs, nephrocytes and a centralized nervous system [1]. The systematic classification of the genus has substantially changed in the last decades, with first being considered as its own phylum (Xenoturbellida) and then being clustered together with acoels and nemertodermatids into the phylum Xenacoelomorpha [4,5]. The phylogenetic position of the xenacoelomorphs has been recalcitrant to resolution, with its position ranging from being the sister group to Nephrozoa (ie, protostomes and deuterostomes [6]) to the sister group to Ambulacraria (ie, Hemichordata and Echinodermata) in a clade called Xenambulacraria [4]. Recent studies based on expanded datasets and more refined analyses support either topology [7,8]. Either way, it is clear that additional studies on Xenoturbella could provide important insights into the origins of bilaterian traits such as the anus, the nephrons and the evolution of a centralized nervous system.

In any case, we are approaching a qualitative jump in how we understand phylogenomics thanks to efforts derived from the availability of chromosome-level genome assemblies for a growing number of species. Exciting times are ahead for us, evolutionary biologists, to explore what high-quality genomes - in combination with multiomics datasets - will reveal about animal evolution. I am personally really looking forward to it. References 1. Westblad E. (1949). Xenoturbella bocki n.g., n.sp., a peculiar, primitive Turbellarian type. Arkiv för Zoologi 1, 3-29 (1949). 2. Rouse, G. W., Wilson, N. G., Carvajal, J. I. & Vrijenhoek, R. C. New deep-sea species of Xenoturbella and the position of Xenacoelomorpha. Nature 530, 94–97 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16545 3. Nakano, H. et al. Correction to: A new species of Xenoturbella from the western Pacific Ocean and the evolution of Xenoturbella. BMC Evol. Biol. 18, 1–2 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-018-1190-5https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-018-1190-5 4. Philippe, H. et al. Acoelomorph flatworms are deuterostomes related to Xenoturbella. Nature 470, 255–258 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09676 5. Hejnol, A. et al. Assessing the root of bilaterian animals with scalable phylogenomic methods. Proc. Biol. Sci. 276, 4261–4270 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2009.0896 6. Cannon, J. T. et al. Xenacoelomorpha is the sister group to Nephrozoa. Nature 530, 89–93 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16520 7. Laumer, C. E. et al. Revisiting metazoan phylogeny with genomic sampling of all phyla. Proc. Biol. Sci. 286, 20190831 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2019.0831 8. Philippe, H. et al. Mitigating anticipated effects of systematic errors supports sister-group relationship between Xenacoelomorpha and Ambulacraria. Curr. Biol. 29, 1818–1826.e6 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.04.009 9. Schiffer, P. H., Natsidis, P., Leite D. J., Robertson, H., Lapraz, F., Marlétaz, F., Fromm, B., Baudry, L., Simpson, F., Høye, E., Zakrzewski, A-C., Kapli, P., Hoff, K. J., Mueller, S., Marbouty, M., Marlow, H., Copley, R. R., Koszul, R., Sarkies, P. & Telford, M .J. The slow evolving genome of the xenacoelomorph worm Xenoturbella bocki. bioRxiv (2023), ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.24.497508 10. Suga, H. et al. The Capsaspora genome reveals a complex unicellular prehistory of animals. Nat. Commun. 4, 2325 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3325 11. Fernández, R. & Gabaldón, T. Gene gain and loss across the metazoan tree of life. Nat Ecol Evol 4, 524–533 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-019-1069-x | The slow evolving genome of the xenacoelomorph worm *Xenoturbella bocki* | Philipp H. Schiffer, Paschalis Natsidis, Daniel J. Leite, Helen Robertson, François Lapraz, Ferdinand Marlétaz, Bastian Fromm, Liam Baudry, Fraser Simpson, Eirik Høye, Anne-C. Zakrzewski, Paschalia Kapli, Katharina J. Hoff, Steven Mueller, Martial... | <p style="text-align: justify;">The evolutionary origins of Bilateria remain enigmatic. One of the more enduring proposals highlights similarities between a cnidarian-like planula larva and simple acoel-like flatworms. This idea is based in part o... |  | Evolutionary genomics | Rosa Fernandez | 2022-11-01 12:31:53 | View | |

06 Feb 2024

The need of decoding life for taking care of biodiversity and the sustainable use of nature in the Anthropocene - a Faroese perspectiveSvein-Ole Mikalsen, Jari í Hjøllum, Ian Salter, Anni Djurhuus, Sunnvør í Kongsstovu https://doi.org/10.32942/X21S4CWhy sequence everything? A raison d’être for the Genome Atlas of Faroese EcologyRecommended by Stephen Richards based on reviews by Tereza Manousaki and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Tereza Manousaki and 1 anonymous reviewer

When discussing the Earth BioGenome Project with scientists and potential funding agencies, one common question is: why sequence everything? Whether sequencing a subset would be more optimal is not an unreasonable question given what we know about the mathematics of importance and Pareto’s 80:20 principle, that 80% of the benefits can come from 20% of the effort. However, one must remember that this principle is an observation made in hindsight and selecting the most effective 20% of experiments is difficult. As an example, few saw great applied value in comparative genomic analysis of the archaea Haloferax mediterranei, but this enabled the discovery of CRISPR/Cas9 technology (1). When discussing whether or not to sequence all life on our planet, smaller countries such as the Faroe Islands are seldom mentioned.

1 Mojica, F. J., Díez-Villaseñor, C. S., García-Martínez, J. & Soria, E. Intervening sequences of regularly spaced prokaryotic repeats derive from foreign genetic elements. J Mol Evol 60, 174-182 (2005). 2 Mikalsen, S-O., Hjøllum, J. í., Salter, I., Djurhuus, A. & Kongsstovu, S. í. The need of decoding life for taking care of biodiversity and the sustainable use of nature in the Anthropocene – a Faroese perspective. EcoEvoRxiv (2024), ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.32942/X21S4C | The need of decoding life for taking care of biodiversity and the sustainable use of nature in the Anthropocene - a Faroese perspective | Svein-Ole Mikalsen, Jari í Hjøllum, Ian Salter, Anni Djurhuus, Sunnvør í Kongsstovu | <p>Biodiversity is under pressure, mainly due to human activities and climate change. At the international policy level, it is now recognised that genetic diversity is an important part of biodiversity. The availability of high-quality reference g... |  | ERGA, ERGA Pilot, Population genomics, Vertebrates | Stephen Richards | 2023-07-31 16:59:33 | View | |

06 Jul 2021

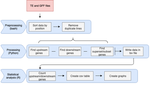

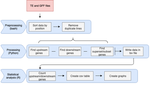

A pipeline to detect the relationship between transposable elements and adjacent genes in host genomesCaroline Meguerditchian, Ayse Ergun, Veronique Decroocq, Marie Lefebvre, Quynh-Trang Bui https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.25.432867A new tool to cross and analyze TE and gene annotationsRecommended by Emmanuelle Lerat based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersTransposable elements (TEs) are important components of genomes. Indeed, they are now recognized as having a major role in gene and genome evolution (Biémont 2010). In particular, several examples have shown that the presence of TEs near genes may influence their functioning, either by recruiting particular epigenetic modifications (Guio et al. 2018) or by directly providing new regulatory sequences allowing new expression patterns (Chung et al. 2007; Sundaram et al. 2014). Therefore, the study of the interaction between TEs and their host genome requires tools to easily cross-annotate both types of entities. In particular, one needs to be able to identify all TEs located in the close vicinity of genes or inside them. Such task may not always be obvious for many biologists, as it requires informatics knowledge to develop their own script codes. In their work, Meguerdichian et al. (2021) propose a command-line pipeline that takes as input the annotations of both genes and TEs for a given genome, then detects and reports the positional relationships between each TE insertion and their closest genes. The results are processed into an R script to provide tables displaying some statistics and graphs to visualize these relationships. This tool has the potential to be very useful for performing preliminary analyses before studying the impact of TEs on gene functioning, especially for biologists. Indeed, it makes it possible to identify genes close to TE insertions. These identified genes could then be specifically considered in order to study in more detail the link between the presence of TEs and their functioning. For example, the identification of TEs close to genes may allow to determine their potential role on gene expression. References Biémont C (2010). A brief history of the status of transposable elements: from junk DNA to major players in evolution. Genetics, 186, 1085–1093. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.110.124180 Chung H, Bogwitz MR, McCart C, Andrianopoulos A, ffrench-Constant RH, Batterham P, Daborn PJ (2007). Cis-regulatory elements in the Accord retrotransposon result in tissue-specific expression of the Drosophila melanogaster insecticide resistance gene Cyp6g1. Genetics, 175, 1071–1077. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.106.066597 Guio L, Vieira C, González J (2018). Stress affects the epigenetic marks added by natural transposable element insertions in Drosophila melanogaster. Scientific Reports, 8, 12197. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-30491-w Meguerditchian C, Ergun A, Decroocq V, Lefebvre M, Bui Q-T (2021). A pipeline to detect the relationship between transposable elements and adjacent genes in host genomes. bioRxiv, 2021.02.25.432867, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.25.432867 Sundaram V, Cheng Y, Ma Z, Li D, Xing X, Edge P, Snyder MP, Wang T (2014). Widespread contribution of transposable elements to the innovation of gene regulatory networks. Genome Research, 24, 1963–1976. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.168872.113 | A pipeline to detect the relationship between transposable elements and adjacent genes in host genomes | Caroline Meguerditchian, Ayse Ergun, Veronique Decroocq, Marie Lefebvre, Quynh-Trang Bui | <p>Understanding the relationship between transposable elements (TEs) and their closest positional genes in the host genome is a key point to explore their potential role in genome evolution. Transposable elements can regulate and affect gene expr... |  | Bioinformatics, Viruses and transposable elements | Emmanuelle Lerat | 2021-03-03 15:08:34 | View |