Latest recommendations

| Id | Title▼ | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

09 Aug 2023

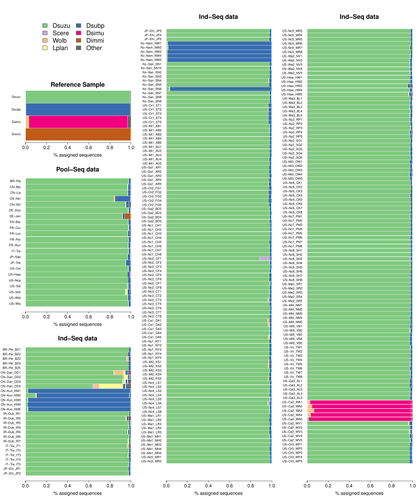

Efficient k-mer based curation of raw sequence data: application in Drosophila suzukiiGautier Mathieu https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.18.537389Decontaminating reads, not contigsRecommended by Nicolas Galtier based on reviews by Marie Cariou and Denis BaurainContamination, the presence of foreign DNA sequences in a sample of interest, is currently a major problem in genomics. Because contamination is often unavoidable at the experimental stage, it is increasingly recognized that the processing of high-throughput sequencing data must include a decontamination step. This is usually performed after the many sequence reads have been assembled into a relatively small number of contigs. Dubious contigs are then discarded based on their composition (e.g. GC-content) or because they are highly similar to a known piece of DNA from a foreign species. Here [1], Mathieu Gautier explores a novel strategy consisting in decontaminating reads, not contigs. Why is this promising? Assembly programs and algorithms are complex, and it is not easy to predict, or monitor, how they handle contaminant reads. Ideally, contaminant reads will be assembled into obvious contaminant contigs. However, there might be more complex situations, such as chimeric contigs with alternating genuine and contaminant segments. Decontaminating at the read level, if possible, should eliminate such unfavorable situations where sequence information from contaminant and target samples are intimately intertwined by an assembler. To achieve this aim, Gautier proposes to use methods initially designed for the analysis of metagenomic data. This is pertinent since the decontamination process involves considering a sample as a mixture of different sources of DNA. The programs used here, CLARK and CLARK-L, are based on so-called k-mer analysis, meaning that the similarity between a read to annotate and a reference sequence is measured by how many sub-sequences (of length 31 base pairs for CLARK and 27 base pairs for CLARK-L) they share. This is notoriously more efficient than traditional sequence alignment algorithms when it comes to comparing a very large number of (most often unrelated) sequences. This is, therefore, a reference-based approach, in which the reads from a sample are assigned to previously sequenced genomes based on k-mer content. This original approach is here specifically applied to the case of Drosophila suzukii, an invasive pest damaging fruit production in Europe and America. Fortunately, Drosophila is a genus of insects with abundant genomic resources, including high-quality reference genomes in dozens of species. Having calibrated and validated his pipeline using data sets of known origins, Gautier quantifies in each of 258 presumed D. suzukii samples the proportion of reads that likely belong to other species of fruit flies, or to fruit fly-associated microbes. This proportion is close to one in 16 samples, which clearly correspond to mis-labelled individuals. It is non-negligible in another ~10 samples, which really correspond to D. suzukii individuals. Most of these reads of unexpected origin are contaminants and should be filtered out. Interestingly, one D. suzukii sample contains a substantial proportion of reads from the closely related D. subpulchera, which might instead reflect a recent episode of gene flow between these two species. The approach, therefore, not only serves as a crucial technical step, but also has the potential to reveal biological processes. Gautier's thorough, well-documented work will clearly benefit the ongoing and future research on D. suzuki, and Drosophila genomics in general. The author and reviewers rightfully note that, like any reference-based approach, this method is heavily dependent on the availability and quality of reference genomes - Drosophila being a favorable case. Building the reference database is a key step, and the interpretation of the output can only be made in the light of its content and gaps, as illustrated by Gautier's careful and detailed discussion of his numerous results. This pioneering study is a striking demonstration of the potential of metagenomic methods for the decontamination of high-throughput sequence data at the read level. The pipeline requires remarkably few computing resources, ensuring low carbon emission. I am looking forward to seeing it applied to a wide range of taxa and samples.

Reference [1] Gautier Mathieu. Efficient k-mer based curation of raw sequence data: application in Drosophila suzukii. bioRxiv, 2023.04.18.537389, ver. 2, peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.18.537389 | Efficient k-mer based curation of raw sequence data: application in *Drosophila suzukii* | Gautier Mathieu | <p>Several studies have highlighted the presence of contaminated entries in public sequence repositories, calling for special attention to the associated metadata. Here, we propose and evaluate a fast and efficient kmer-based approach to assess th... |  | Bioinformatics, Population genomics | Nicolas Galtier | 2023-04-20 22:05:13 | View | |

18 Jul 2022

CulebrONT: a streamlined long reads multi-assembler pipeline for prokaryotic and eukaryotic genomesJulie Orjuela, Aurore Comte, Sébastien Ravel, Florian Charriat, Tram Vi, Francois Sabot, Sébastien Cunnac https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.19.452922A flexible and reproducible pipeline for long-read assembly and evaluationRecommended by Raúl Castanera based on reviews by Benjamin Istace and Valentine MurigneuxThird-generation sequencing has revolutionised de novo genome assembly. Thanks to this technology, genome reference sequences have evolved from fragmented drafts to gapless, telomere-to-telomere genome assemblies. Long reads produced by Oxford Nanopore and PacBio technologies can span structural variants and resolve complex repetitive regions such as centromeres, unlocking previously inaccessible genomic information. Nowadays, many research groups can afford to sequence the genome of their working model using long reads. Nevertheless, genome assembly poses a significant computational challenge. Read length, quality, coverage and genomic features such as repeat content can affect assembly contiguity, accuracy, and completeness in almost unpredictable ways. Consequently, there is no best universal software or protocol for this task. Producing a high-quality assembly requires chaining several tools into pipelines and performing extensive comparisons between the assemblies obtained by different tool combinations to decide which one is the best. This task can be extremely challenging, as the number of tools available rises very rapidly, and thorough benchmarks cannot be updated and published at such a fast pace. In their paper, Orjuela and collaborators present CulebrONT [1], a universal pipeline that greatly contributes to overcoming these challenges and facilitates long-read genome assembly for all taxonomic groups. CulebrONT incorporates six commonly used assemblers and allows to perform assembly, circularization (if needed), polishing, and evaluation in a simple framework. One important aspect of CulebrONT is its modularity, which allows the activation or deactivation of specific tools, giving great flexibility to the user. Nevertheless, possibly the best feature of CulebrONT is the opportunity to benchmark the selected tool combinations based on the excellent report generated by the pipeline. This HTML report aggregates the output of several tools for quality evaluation of the assemblies (e.g. BUSCO [2] or QUAST [3]) generated by the different assemblers, in addition to the running time and configuration parameters. Such information is of great help to identify the best-suited pipeline, as exemplified by the authors using four datasets of different taxonomic origins. Finally, CulebrONT can handle multiple samples in parallel, which makes it a good solution for laboratories looking for multiple assemblies on a large scale. References 1. Orjuela J, Comte A, Ravel S, Charriat F, Vi T, Sabot F, Cunnac S (2022) CulebrONT: a streamlined long reads multi-assembler pipeline for prokaryotic and eukaryotic genomes. bioRxiv, 2021.07.19.452922, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.19.452922 2. Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM (2015) BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics, 31, 3210–3212. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351 3. Gurevich A, Saveliev V, Vyahhi N, Tesler G (2013) QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics, 29, 1072–1075. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086 | CulebrONT: a streamlined long reads multi-assembler pipeline for prokaryotic and eukaryotic genomes | Julie Orjuela, Aurore Comte, Sébastien Ravel, Florian Charriat, Tram Vi, Francois Sabot, Sébastien Cunnac | <p style="text-align: justify;">Using long reads provides higher contiguity and better genome assemblies. However, producing such high quality sequences from raw reads requires to chain a growing set of tools, and determining the best workflow is ... |  | Bioinformatics | Raúl Castanera | Valentine Murigneux | 2022-02-22 16:21:25 | View |

11 Sep 2023

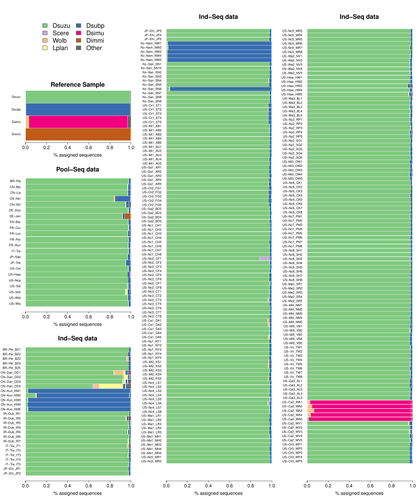

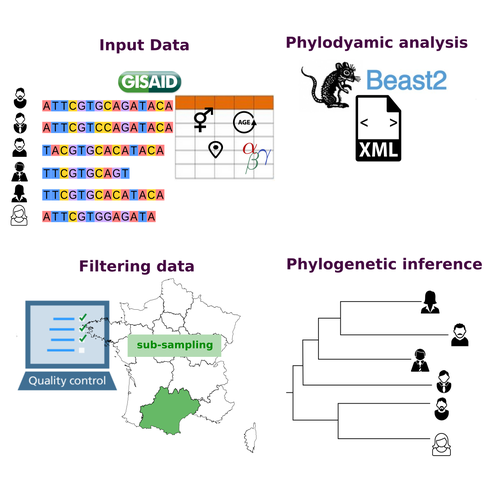

COVFlow: phylodynamics analyses of viruses from selected SARS-CoV-2 genome sequencesGonché Danesh, Corentin Boennec, Laura Verdurme, Mathilde Roussel, Sabine Trombert-Paolantoni, Benoit Visseaux, Stephanie Haim-Boukobza, Samuel Alizon https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.17.496544A pipeline to select SARS-CoV-2 sequences for reliable phylodynamic analysesRecommended by Emmanuelle Lerat based on reviews by Gabriel Wallau and Bastien BoussauPhylodynamic approaches enable viral genetic variation to be tracked over time, providing insight into pathogen phylogenetic relationships and epidemiological dynamics. These are important methods for monitoring viral spread, and identifying important parameters such as transmission rate, geographic origin and duration of infection [1]. This knowledge makes it possible to adjust public health measures in real-time and was important in the case of the COVID-19 pandemic [2]. However, these approaches can be complicated to use when combining a very large number of sequences. This was particularly true during the COVID-19 pandemic, when sequencing data representing millions of entire viral genomes was generated, with associated metadata enabling their precise identification. Danesh et al. [3] present a bioinformatics pipeline, CovFlow, for selecting relevant sequences according to user-defined criteria to produce files that can be used directly for phylodynamic analyses. The selection of sequences first involves a quality filter on the size of the sequences and the absence of unresolved bases before being able to make choices based on the associated metadata. Once the sequences are selected, they are aligned and a time-scaled phylogenetic tree is inferred. An output file in a format directly usable by BEAST 2 [4] is finally generated. To illustrate the use of the pipeline, Danesh et al. [3] present an analysis of the Delta variant in two regions of France. They observed a delay in the start of the epidemic depending on the region. In addition, they identified genetic variation linked to the start of the school year and the extension of vaccination, as well as the arrival of a new variant. This tool will be of major interest to researchers analysing SARS-CoV-2 sequencing data, and a number of future developments are planned by the authors. References [1] Baele G, Dellicour S, Suchard MA, Lemey P, Vrancken B. 2018. Recent advances in computational phylodynamics. Curr Opin Virol. 31:24-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coviro.2018.08.009 [2] Attwood SW, Hill SC, Aanensen DM, Connor TR, Pybus OG. 2022. Phylogenetic and phylodynamic approaches to understanding and combating the early SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Nat Rev Genet. 23:547-562. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-022-00483-8 [3] Danesh G, Boennec C, Verdurme L, Roussel M, Trombert-Paolantoni S, Visseaux B, Haim-Boukobza S, Alizon S. 2023. COVFlow: phylodynamics analyses of viruses from selected SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences. bioRxiv, ver. 7 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.17.496544 [4] Bouckaert R, Heled J, Kühnert D, Vaughan T, Wu C-H et al. 2014. BEAST 2: a software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLoS Comput Biol 10: e1003537. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003537 | COVFlow: phylodynamics analyses of viruses from selected SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences | Gonché Danesh, Corentin Boennec, Laura Verdurme, Mathilde Roussel, Sabine Trombert-Paolantoni, Benoit Visseaux, Stephanie Haim-Boukobza, Samuel Alizon | <p style="text-align: justify;">Phylodynamic analyses generate important and timely data to optimise public health response to SARS-CoV-2 outbreaks and epidemics. However, their implementation is hampered by the massive amount of sequence data and... |  | Bioinformatics, Evolutionary genomics | Emmanuelle Lerat | 2022-12-12 09:04:01 | View | |

15 Mar 2024

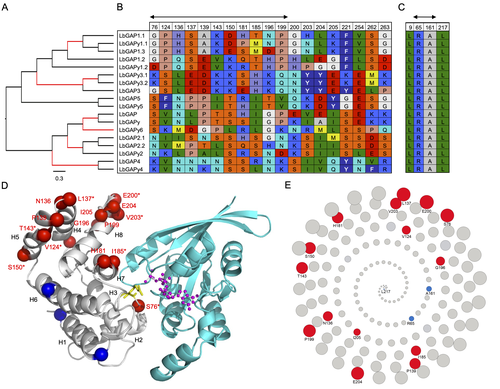

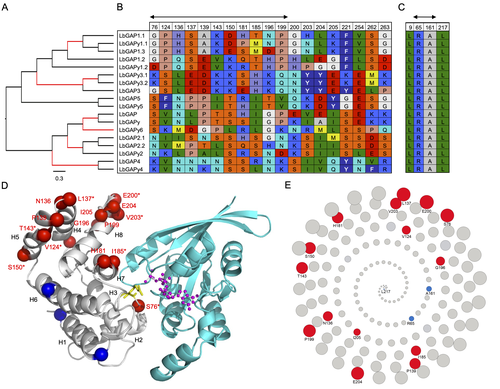

Convergent origin and accelerated evolution of vesicle-associated RhoGAP proteins in two unrelated parasitoid waspsDominique Colinet, Fanny Cavigliasso, Matthieu Leobold, Appoline Pichon, Serge Urbach, Dominique Cazes, Marine Poullet, Maya Belghazi, Anne-Nathalie Volkoff, Jean-Michel Drezen, Jean-Luc Gatti, and Marylène Poirié https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.05.543686Using transcriptomics and proteomics to understand the expansion of a secreted poisonous armoury in parasitoid wasps genomesRecommended by Ignacio Bravo based on reviews by Inacio Azevedo and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Inacio Azevedo and 2 anonymous reviewers

Parasitoid wasps lay their eggs inside another arthropod, whose body is physically consumed by the parasitoid larvae. Phylogenetic inference suggests that Parasitoida are monophyletic, and that this clade underwent a strong radiation shortly after branching off from the Apocrita stem, some 236 million years ago (Peters et al. 2017). The increase in taxonomic diversity during evolutionary radiations is usually concurrent with an increase in genetic/genomic diversity, and is often associated with an increase in phenotypic diversity. Gene (or genome) duplication provides the evolutionary potential for such increase of genomic diversity by neo/subfunctionalisation of one of the gene paralogs, and is often proposed to be related to evolutionary radiations (Ohno 1970; Francino 2005).

References

| Convergent origin and accelerated evolution of vesicle-associated RhoGAP proteins in two unrelated parasitoid wasps | Dominique Colinet, Fanny Cavigliasso, Matthieu Leobold, Appoline Pichon, Serge Urbach, Dominique Cazes, Marine Poullet, Maya Belghazi, Anne-Nathalie Volkoff, Jean-Michel Drezen, Jean-Luc Gatti, and Marylène Poirié | <p>Animal venoms and other protein-based secretions that perform a variety of functions, from predation to defense, are highly complex cocktails of bioactive compounds. Gene duplication, accompanied by modification of the expression and/or functio... |  | Evolutionary genomics | Ignacio Bravo | 2023-06-12 11:08:31 | View | |

12 Jul 2022

Chromosome-level genome assembly and annotation of two lineages of the ant Cataglyphis hispanica: steppingstones towards genomic studies of hybridogenesis and thermal adaptation in desert antsHugo Darras, Natalia de Souza Araujo, Lyam Baudry, Nadège Guiglielmoni, Pedro Lorite, Martial Marbouty, Fernando Rodriguez, Irina Arkhipova, Romain Koszul, Jean-François Flot, Serge Aron https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.07.475286A genomic resource for ants, and moreRecommended by Nadia Ponts based on reviews by Isabel Almudi and Nicolas NègreThe ant species Cataglyphis hispanica is remarkably well adapted to arid habitats of the Iberian Peninsula where two hybridogenetic lineages co-occur, i.e., queens mating with males from the other lineage produce only non-reproductive hybrid workers whereas reproductive males and females are produced by parthenogenesis (Lavanchy and Schwander, 2019). For these two reasons, the genomes of these lineages, Chis1 and Chis2, are potential gold mines to explore the genetic bases of thermal adaptation and the evolution of alternative reproductive modes. Nowadays, sequencing technology enables assembling all kinds of genomes provided genomic DNA can be extracted. More difficult to achieve is high-quality assemblies with just as high-quality annotations that are readily available to the community to be used and re-used at will (Byrne et al., 2019; Salzberg, 2019). The challenge was successfully completed by Darras and colleagues, the generated resource being fully available to the community, including scripts and command lines used to obtain the proposed results. The authors particularly describe that lineage Chis2 has 27 chromosomes, against 26 or 27 for lineage Chis1, with a Robertsonian translocation identified by chromosome conformation capture (Duan et al., 2010, 2012) in the two Queens sequenced. Transcript-supported gene annotation provided 11,290 high-quality gene models. In addition, an ant-tailored annotation pipeline identified 56 different families of repetitive elements in both Chis1 and Chis2 lineages of C. hispanica spread in a little over 15 % of the genome. Altogether, the genomes of Chis1 and Chis2 are highly similar and syntenic, with some level of polymorphism raising questions about their evolutionary story timeline. In particular, the uniform distribution of polymorphisms along the genomes shakes up a previous hypothesis of hybridogenetic lineage pairs determined by ancient non-recombining regions (Linksvayer, Busch and Smith, 2013). I recommend this paper because the science behind is both solid and well-explained. The provided resource is of high quality, and accompanied by a critical exploration of the perspectives brought by the results. These genomes are excellent resources to now go further in exploring the possible events at the genome level that accompanied the remarkable thermal adaptation of the ants Cataglyphis, as well as insights into the genetics of hybridogenetic lineages. Beyond the scientific value of the resources and insights provided by the work performed, I also recommend this article because it is an excellent example of Open Science (Allen and Mehler, 2019; Sarabipour et al., 2019), all data methods and tools being fully and easily accessible to whoever wants/needs it. References Allen C, Mehler DMA (2019) Open science challenges, benefits and tips in early career and beyond. PLOS Biology, 17, e3000246. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000246 Byrne A, Cole C, Volden R, Vollmers C (2019) Realizing the potential of full-length transcriptome sequencing. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 374, 20190097. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0097 Darras H, de Souza Araujo N, Baudry L, Guiglielmoni N, Lorite P, Marbouty M, Rodriguez F, Arkhipova I, Koszul R, Flot J-F, Aron S (2022) Chromosome-level genome assembly and annotation of two lineages of the ant Cataglyphis hispanica: stepping stones towards genomic studies of hybridogenesis and thermal adaptation in desert ants. bioRxiv, 2022.01.07.475286, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.07.475286 Duan Z, Andronescu M, Schutz K, Lee C, Shendure J, Fields S, Noble WS, Anthony Blau C (2012) A genome-wide 3C-method for characterizing the three-dimensional architectures of genomes. Methods, 58, 277–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.06.018 Duan Z, Andronescu M, Schutz K, McIlwain S, Kim YJ, Lee C, Shendure J, Fields S, Blau CA, Noble WS (2010) A three-dimensional model of the yeast genome. Nature, 465, 363–367. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08973 Lavanchy G, Schwander T (2019) Hybridogenesis. Current Biology, 29, R9–R11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2018.11.046 Linksvayer TA, Busch JW, Smith CR (2013) Social supergenes of superorganisms: Do supergenes play important roles in social evolution? BioEssays, 35, 683–689. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.201300038 Salzberg SL (2019) Next-generation genome annotation: we still struggle to get it right. Genome Biology, 20, 92. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-019-1715-2 Sarabipour S, Debat HJ, Emmott E, Burgess SJ, Schwessinger B, Hensel Z (2019) On the value of preprints: An early career researcher perspective. PLOS Biology, 17, e3000151. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000151 | Chromosome-level genome assembly and annotation of two lineages of the ant Cataglyphis hispanica: steppingstones towards genomic studies of hybridogenesis and thermal adaptation in desert ants | Hugo Darras, Natalia de Souza Araujo, Lyam Baudry, Nadège Guiglielmoni, Pedro Lorite, Martial Marbouty, Fernando Rodriguez, Irina Arkhipova, Romain Koszul, Jean-François Flot, Serge Aron | <p style="text-align: justify;"><em>Cataglyphis</em> are thermophilic ants that forage during the day when temperatures are highest and sometimes close to their critical thermal limit. Several Cataglyphis species have evolved unusual reproductive ... |  | Evolutionary genomics | Nadia Ponts | Nicolas Nègre, Isabel Almudi | 2022-01-13 16:47:30 | View |

23 Mar 2022

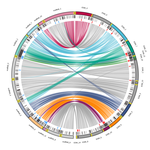

Chromosomal rearrangements with stable repertoires of genes and transposable elements in an invasive forest-pathogenic fungusArthur Demene, Benoit Laurent, Sandrine Cros-Arteil, Christophe Boury, Cyril Dutech https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.09.434572Comparative genomics in the chestnut blight fungus Cryphonectria parasitica reveals large chromosomal rearrangements and a stable genome organizationRecommended by Sebastien Duplessis based on reviews by Benjamin Schwessinger and 1 anonymous reviewerAbout twenty-five years after the sequencing of the first fungal genome and a dozen years after the first plant pathogenic fungi genomes were sequenced, unprecedented international efforts have led to an impressive collection of genomes available for the community of mycologists in international databases (Goffeau et al. 1996, Dean et al. 2005; Spatafora et al. 2017). For instance, to date, the Joint Genome Institute Mycocosm database has collected more than 2,100 fungal genomes over the fungal tree of life (https://mycocosm.jgi.doe.gov). Such resources are paving the way for comparative genomics, population genomics and phylogenomics to address a large panel of questions regarding the biology and the ecology of fungal species. Early on, population genomics applied to pathogenic fungi revealed a great diversity of genome content and organization and a wide variety of variants and rearrangements (Raffaele and Kamoun 2012, Hartmann 2022). Such plasticity raises questions about how to choose a representative genome to serve as an ideal reference to address pertinent biological questions. Cryphonectria parasitica is a fungal pathogen that is infamous for the devastation of chestnut forests in North America after its accidental introduction more than a century ago (Anagnostakis 1987). Since then, it has been a quarantine species under surveillance in various parts of the world. As for other fungi causing diseases on forest trees, the study of adaptation to its host in the forest ecosystem and of its reproduction and dissemination modes is more complex than for crop-targeting pathogens. A first reference genome was published in 2020 for the chestnut blight fungus C. parasitica strain EP155 in the frame of an international project with the DOE JGI (Crouch et al. 2020). Another genome was then sequenced from the French isolate YVO003, which showed a few differences in the assembly suggesting possible rearrangements (Demené et al. 2019). Here the sequencing of a third isolate ESM015 from the native area of C. parasitica in Japan allows to draw broader comparative analysis and particularly to compare between native and introduced isolates (Demené et al. 2022). Demené and collaborators report on a new genome sequence using up-to-date long-read sequencing technologies and they provide an improved genome assembly. Comparison with previously published C. parasitica genomes did not reveal dramatic changes in the overall chromosomal landscapes, but large rearrangements could be spotted. Despite these rearrangements, the genome content and organization – i.e. genes and repeats – remain stable, with a limited number of genes gains and losses. As in any fungal plant pathogen genome, the repertoire of candidate effectors predicted among secreted proteins was more particularly scrutinized. Such effector genes have previously been reported in other pathogens in repeat-enriched plastic genomic regions with accelerated evolutionary rates under the pressure of the host immune system (Raffaele and Kamoun 2012). Demené and collaborators established a list of priority candidate effectors in the C. parasitica gene catalog likely involved in the interaction with the host plant which will require more attention in future functional studies. Six major inter-chromosomal translocations were detected and are likely associated with double break strands repairs. The authors speculate on the possible effects that these translocations may have on gene organization and expression regulation leading to dramatic phenotypic changes in relation to introduction and invasion in new continents and the impact regarding sexual reproduction in this fungus (Demené et al. 2022). I recommend this article not only because it is providing an improved assembly of a reference genome for C. parasitica, but also because it adds diversity in terms of genome references availability, with a third high-quality assembly. Such an effort in the tree pathology community for a pathogen under surveillance is of particular importance for future progress in post-genomic analysis, e.g. in further genomic population studies (Hartmann 2022). References Anagnostakis SL (1987) Chestnut Blight: The Classical Problem of an Introduced Pathogen. Mycologia, 79, 23–37. https://doi.org/10.2307/3807741 Crouch JA, Dawe A, Aerts A, Barry K, Churchill ACL, Grimwood J, Hillman BI, Milgroom MG, Pangilinan J, Smith M, Salamov A, Schmutz J, Yadav JS, Grigoriev IV, Nuss DL (2020) Genome Sequence of the Chestnut Blight Fungus Cryphonectria parasitica EP155: A Fundamental Resource for an Archetypical Invasive Plant Pathogen. Phytopathology®, 110, 1180–1188. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-12-19-0478-A Dean RA, Talbot NJ, Ebbole DJ, Farman ML, Mitchell TK, Orbach MJ, Thon M, Kulkarni R, Xu J-R, Pan H, Read ND, Lee Y-H, Carbone I, Brown D, Oh YY, Donofrio N, Jeong JS, Soanes DM, Djonovic S, Kolomiets E, Rehmeyer C, Li W, Harding M, Kim S, Lebrun M-H, Bohnert H, Coughlan S, Butler J, Calvo S, Ma L-J, Nicol R, Purcell S, Nusbaum C, Galagan JE, Birren BW (2005) The genome sequence of the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Nature, 434, 980–986. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03449 Demené A., Laurent B., Cros-Arteil S., Boury C. and Dutech C. 2022. Chromosomal rearrangements with stable repertoires of genes and transposable elements in an invasive forest-pathogenic fungus. bioRxiv, 2021.03.09.434572, ver.6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.09.434572 Goffeau A, Barrell BG, Bussey H, Davis RW, Dujon B, Feldmann H, Galibert F, Hoheisel JD, Jacq C, Johnston M, Louis EJ, Mewes HW, Murakami Y, Philippsen P, Tettelin H, Oliver SG (1996) Life with 6000 Genes. Science, 274, 546–567. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.274.5287.546 Hartmann FE (2022) Using structural variants to understand the ecological and evolutionary dynamics of fungal plant pathogens. New Phytologist, 234, 43–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.17907 Raffaele S, Kamoun S (2012) Genome evolution in filamentous plant pathogens: why bigger can be better. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 10, 417–430. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2790 Spatafora JW, Aime MC, Grigoriev IV, Martin F, Stajich JE, Blackwell M (2017) The Fungal Tree of Life: from Molecular Systematics to Genome-Scale Phylogenies. Microbiology Spectrum, 5, 5.5.03. https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.FUNK-0053-2016 | Chromosomal rearrangements with stable repertoires of genes and transposable elements in an invasive forest-pathogenic fungus | Arthur Demene, Benoit Laurent, Sandrine Cros-Arteil, Christophe Boury, Cyril Dutech | <p style="text-align: justify;">Chromosomal rearrangements have been largely described among eukaryotes, and may have important consequences on evolution of species. High genome plasticity has been often reported in Fungi, which may explain their ... |  | Evolutionary genomics, Fungi | Sebastien Duplessis | 2021-03-12 14:18:20 | View | |

20 Nov 2023

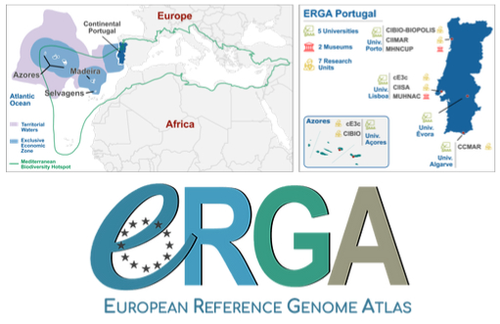

Building a Portuguese Coalition for Biodiversity GenomicsJoão Pedro Marques, Paulo Célio Alves, Isabel R. Amorim, Ricardo J. Lopes, Mónica Moura, Gene Meyers, Manuela Sim-Sim, Carla Sousa-Santos, Maria Judite Alves, Paulo AV Borges, Thomas Brown, Miguel Carneiro, Carlos Carrapato, Luís Ceríaco, Claudio Ciofi, Luís da Silva, Genevieve Diedericks, Maria Angela Diroma, Liliana Farelo, Giulio Formenti, Fátima Gil, Miguel Grilo, Alessio Ianucci, Henrique Leitão, Cristina Máguas, Ann Mc Cartney, Sofia Mendes, João Moreno, Marco Morselli, Alice Mouton, Chiar... https://doi.org/10.32942/X20W3QThe Portuguese genomics community teams up with iconic species to understand the destruction of biodiversityRecommended by Fernando Racimo based on reviews by Svein-Ole Mikalsen and 1 anonymous reviewerThis manuscript describes the ongoing work and plans of Biogenome Portugal: a new network of researchers in the Portuguese biodiversity genomics community. The aims of this network are to jointly train scientists in ecology and evolution, generate new knowledge and understanding of Portuguese biodiversity, and better engage with the public and with international researchers, so as to advance conservation efforts in the region. In collaboration across disciplines and institutions, they are also contributing to the European Reference Genome Atlas (ERGA): a massive scientific effort, seeking to eventually produce reference-quality genomes for all species in the European continent (Mc Cartney et al. 2023). The manuscript centers around six iconic and/or severely threatened species, whose range extends across parts of what is today considered Portuguese territory. Via the Portugal chapter of ERGA (ERGA-Portugal), the researchers will generate high-quality genome sequences from these species. The species are the Iberian hare, the Azores laurel, the Black wheatear, the Portuguese crowberry, the Cave ground beetle and the Iberian minnowcarp. In ignorance of human-made political borders, some of these species also occupy large parts of the rest of the Iberian peninsula, highlighting the importance of transnational collaboration in biodiversity efforts. The researchers extracted samples from members of each of these species, and are building reference genome sequences from them. In some cases, these sequences will also be co-analyzed with additional population genomic data from the same species or genetic data from cohabiting species. The researchers aim to answer a variety of ecological and evolutionary questions using this information, including how genetic diversity is being affected by the destruction of their habitat, and how they are being forced to adapt as a consequence of the climate emergency. The authors did a very good job in providing a justification for the choice of pilot species, a thorough methodological overview of current work, and well thought-out plans for future analyses once the genome sequences are available for study. The authors also describe plans for networking and training activities to foster a well-connected Portuguese biodiversity genomics community. Applying a genomic analysis lens is important for understanding the ever faster process of devastation of our natural world. Governments and corporations around the globe are destroying nature at ever larger scales (Diaz et al. 2019). They are also destabilizing the climatic conditions on which life has existed for thousands of years (Trisos et al. 2020). Thus, genetic diversity is decreasing faster than ever in human history, even when it comes to non-threatened species (Exposito-Alonso et al. 2022), and these decreases are disrupting ecological processes worldwide (Richardson et al. 2023). This, in turn, is threatening the conditions on which the stability of our societies rest (Gardner and Bullock 2021). The efforts of Biogenome Portal and ERGA-Portugal will go a long way in helping us understand in greater detail how this process is unfolding in Portuguese territories.

References Díaz, Sandra, et al. "Pervasive human-driven decline of life on Earth points to the need for transformative change." Science 366.6471 (2019): eaax3100. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax3100 Exposito-Alonso, Moises, et al. "Genetic diversity loss in the Anthropocene." Science 377.6613 (2022): 1431-1435. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn5642 Gardner, Charlie J., and James M. Bullock. "In the climate emergency, conservation must become survival ecology." Frontiers in Conservation Science 2 (2021): 659912. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcosc.2021.659912 Mc Cartney, Ann M., et al. "The European Reference Genome Atlas: piloting a decentralised approach to equitable biodiversity genomics." bioRxiv (2023): 2023-09, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.32942/X20W3Q Richardson, Katherine, et al. "Earth beyond six of nine planetary boundaries." Science Advances 9.37 (2023): eadh2458. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adh2458 Trisos, Christopher H., Cory Merow, and Alex L. Pigot. "The projected timing of abrupt ecological disruption from climate change." Nature 580.7804 (2020): 496-501. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2189-9 | Building a Portuguese Coalition for Biodiversity Genomics | João Pedro Marques, Paulo Célio Alves, Isabel R. Amorim, Ricardo J. Lopes, Mónica Moura, Gene Meyers, Manuela Sim-Sim, Carla Sousa-Santos, Maria Judite Alves, Paulo AV Borges, Thomas Brown, Miguel Carneiro, Carlos Carrapato, Luís Ceríaco, Claudio ... | <p style="text-align: justify;">The diverse physiography of the Portuguese land and marine territory, spanning from continental Europe to the Atlantic archipelagos, has made it an important repository of biodiversity throughout the Pleistocene gla... |  | ERGA, ERGA Pilot | Fernando Racimo | 2023-07-14 11:24:22 | View | |

15 Dec 2022

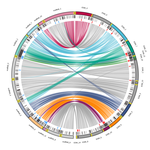

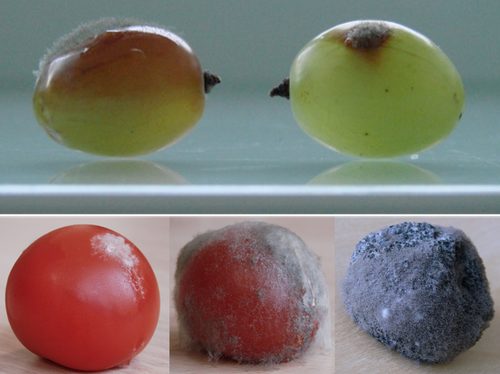

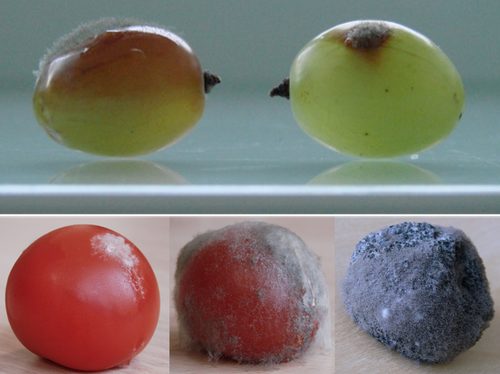

Botrytis cinerea strains infecting grapevine and tomato display contrasted repertoires of accessory chromosomes, transposons and small RNAsAdeline Simon, Alex Mercier, Pierre Gladieux, Benoit Poinssot, Anne-Sophie Walker, Muriel Viaud https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.07.483234Exploring genomic determinants of host specialization in Botrytis cinereaRecommended by Sebastien Duplessis based on reviews by Cecile Lorrain and Thorsten LangnerThe genomics era has pushed forward our understanding of fungal biology. Much progress has been made in unraveling new gene functions and pathways, as well as the evolution or adaptation of fungi to their hosts or environments through population studies (Hartmann et al. 2019; Gladieux et al. 2018). Closing gaps more systematically in draft genomes using the most recent long-read technologies now seems the new standard, even with fungal species presenting complex genome structures (e.g. large and highly repetitive dikaryotic genomes; Duan et al. 2022). Understanding the genomic dynamics underlying host specialization in phytopathogenic fungi is of utmost importance as it may open new avenues to combat diseases. A strong host specialization is commonly observed for biotrophic and hemi-biotrophic fungal species or for necrotrophic fungi with a narrow host range, whereas necrotrophic fungi with broad host range are considered generalists (Liang and Rollins, 2018; Newman and Derbyshire, 2020). However, some degrees of specialization towards given hosts have been reported in generalist fungi and the underlying mechanisms remain to be determined. Botrytis cinerea is a polyphagous necrotrophic phytopathogen with a particularly wide host range and it is notably responsible for grey mould disease on many fruits, such as tomato and grapevine. Because of its importance as a plant pathogen, its relatively small genome size and its taxonomical position, it has been targeted for early genome sequencing and a first reference genome was provided in 2011 (Amselem et al. 2011). Other genomes were subsequently sequenced for other strains, and most importantly a gapless assembled version of the initial reference genome B05.10 was provided to the community (van Kan et al. 2017). This genomic resource has supported advances in various aspects of the biology of B. cinerea such as the production of specialized metabolites, which plays an important role in host-plant colonization, or more recently in the production of small RNAs which interfere with the host immune system, representing a new class of non-proteinaceous virulence effectors (Dalmais et al. 2011; Weiberg et al. 2013). In the present study, Simon et al. (2022) use PacBio long-read sequencing for Sl3 and Vv3 strains, which represent genetic clusters in B. cinerea populations found on tomato and grapevine. The authors combined these complete and high-quality genome assemblies with the B05.10 reference genome and population sequencing data to perform a comparative genomic analysis of specialization towards the two host plants. Transposable elements generate genomic diversity due to their mobile and repetitive nature and they are of utmost importance in the evolution of fungi as they deeply reshape the genomic landscape (Lorrain et al. 2021). Accessory chromosomes are also known drivers of adaptation in fungi (Möller and Stukenbrock, 2017). Here, the authors identify several genomic features such as the presence of different sets of accessory chromosomes, the presence of differentiated repertoires of transposable elements, as well as related small RNAs in the tomato and grapevine populations, all of which may be involved in host specialization. Whereas core chromosomes are highly syntenic between strains, an accessory chromosome validated by pulse-field electrophoresis is specific of the strains isolated from grapevine. Particularly, they show that two particular retrotransposons are discriminant between the strains and that they allow the production of small RNAs that may act as effectors. The discriminant accessory chromosome of the Vv3 strain harbors one of the unraveled retrotransposons as well as new genes of yet unidentified function. I recommend this article because it perfectly illustrates how efforts put into generating reference genomic sequences of higher quality can lead to new discoveries and allow to build strong hypotheses about biology and evolution in fungi. Also, the study combines an up-to-date genomics approach with a classical methodology such as pulse-field electrophoresis to validate the presence of accessory chromosomes. A major input of this investigation of the genomic determinants of B. cinerea is that it provides solid hints for further analysis of host-specialization at the population level in a broad-scale phytopathogenic fungus. References Amselem J, Cuomo CA, Kan JAL van, Viaud M, Benito EP, Couloux A, Coutinho PM, Vries RP de, Dyer PS, Fillinger S, Fournier E, Gout L, Hahn M, Kohn L, Lapalu N, Plummer KM, Pradier J-M, Quévillon E, Sharon A, Simon A, Have A ten, Tudzynski B, Tudzynski P, Wincker P, Andrew M, Anthouard V, Beever RE, Beffa R, Benoit I, Bouzid O, Brault B, Chen Z, Choquer M, Collémare J, Cotton P, Danchin EG, Silva CD, Gautier A, Giraud C, Giraud T, Gonzalez C, Grossetete S, Güldener U, Henrissat B, Howlett BJ, Kodira C, Kretschmer M, Lappartient A, Leroch M, Levis C, Mauceli E, Neuvéglise C, Oeser B, Pearson M, Poulain J, Poussereau N, Quesneville H, Rascle C, Schumacher J, Ségurens B, Sexton A, Silva E, Sirven C, Soanes DM, Talbot NJ, Templeton M, Yandava C, Yarden O, Zeng Q, Rollins JA, Lebrun M-H, Dickman M (2011) Genomic Analysis of the Necrotrophic Fungal Pathogens Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and Botrytis cinerea. PLOS Genetics, 7, e1002230. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002230 Dalmais B, Schumacher J, Moraga J, Le Pêcheur P, Tudzynski B, Collado IG, Viaud M (2011) The Botrytis cinerea phytotoxin botcinic acid requires two polyketide synthases for production and has a redundant role in virulence with botrydial. Molecular Plant Pathology, 12, 564–579. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1364-3703.2010.00692.x Duan H, Jones AW, Hewitt T, Mackenzie A, Hu Y, Sharp A, Lewis D, Mago R, Upadhyaya NM, Rathjen JP, Stone EA, Schwessinger B, Figueroa M, Dodds PN, Periyannan S, Sperschneider J (2022) Physical separation of haplotypes in dikaryons allows benchmarking of phasing accuracy in Nanopore and HiFi assemblies with Hi-C data. Genome Biology, 23, 84. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-022-02658-2 Gladieux P, Condon B, Ravel S, Soanes D, Maciel JLN, Nhani A, Chen L, Terauchi R, Lebrun M-H, Tharreau D, Mitchell T, Pedley KF, Valent B, Talbot NJ, Farman M, Fournier E (2018) Gene Flow between Divergent Cereal- and Grass-Specific Lineages of the Rice Blast Fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. mBio, 9, e01219-17. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.01219-17 Hartmann FE, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, Carpentier F, Gladieux P, Cornille A, Hood ME, Giraud T (2019) Understanding Adaptation, Coevolution, Host Specialization, and Mating System in Castrating Anther-Smut Fungi by Combining Population and Comparative Genomics. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 57, 431–457. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-phyto-082718-095947 Liang X, Rollins JA (2018) Mechanisms of Broad Host Range Necrotrophic Pathogenesis in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Phytopathology®, 108, 1128–1140. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-06-18-0197-RVW Lorrain C, Oggenfuss U, Croll D, Duplessis S, Stukenbrock E (2021) Transposable Elements in Fungi: Coevolution With the Host Genome Shapes, Genome Architecture, Plasticity and Adaptation. In: Encyclopedia of Mycology (eds Zaragoza Ó, Casadevall A), pp. 142–155. Elsevier, Oxford. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-819990-9.00042-1 Möller M, Stukenbrock EH (2017) Evolution and genome architecture in fungal plant pathogens. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 15, 756–771. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2017.76 Newman TE, Derbyshire MC (2020) The Evolutionary and Molecular Features of Broad Host-Range Necrotrophy in Plant Pathogenic Fungi. Frontiers in Plant Science, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.591733 Simon A, Mercier A, Gladieux P, Poinssot B, Walker A-S, Viaud M (2022) Botrytis cinerea strains infecting grapevine and tomato display contrasted repertoires of accessory chromosomes, transposons and small RNAs. bioRxiv, 2022.03.07.483234, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.07.483234 Van Kan JAL, Stassen JHM, Mosbach A, Van Der Lee TAJ, Faino L, Farmer AD, Papasotiriou DG, Zhou S, Seidl MF, Cottam E, Edel D, Hahn M, Schwartz DC, Dietrich RA, Widdison S, Scalliet G (2017) A gapless genome sequence of the fungus Botrytis cinerea. Molecular Plant Pathology, 18, 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/mpp.12384 Weiberg A, Wang M, Lin F-M, Zhao H, Zhang Z, Kaloshian I, Huang H-D, Jin H (2013) Fungal Small RNAs Suppress Plant Immunity by Hijacking Host RNA Interference Pathways. Science, 342, 118–123. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1239705 | Botrytis cinerea strains infecting grapevine and tomato display contrasted repertoires of accessory chromosomes, transposons and small RNAs | Adeline Simon, Alex Mercier, Pierre Gladieux, Benoit Poinssot, Anne-Sophie Walker, Muriel Viaud | <p style="text-align: justify;">The fungus <em>Botrytis cinerea</em> is a polyphagous pathogen that encompasses multiple host-specialized lineages. While several secreted proteins, secondary metabolites and retrotransposons-derived small RNAs have... |  | Fungi, Structural genomics, Viruses and transposable elements | Sebastien Duplessis | Cecile Lorrain, Thorsten Langner | 2022-03-15 11:15:48 | View |

24 Sep 2020

A rapid and simple method for assessing and representing genome sequence relatednessM Briand, M Bouzid, G Hunault, M Legeay, M Fischer-Le Saux, M Barret https://doi.org/10.1101/569640A quick alternative method for resolving bacterial taxonomy using short identical DNA sequences in genomes or metagenomesRecommended by B. Jesse Shapiro based on reviews by Gavin Douglas and 1 anonymous reviewerThe bacterial species problem can be summarized as follows: bacteria recombine too little, and yet too much (Shapiro 2019). References Arevalo P, VanInsberghe D, Elsherbini J, Gore J, Polz MF (2019) A Reverse Ecology Approach Based on a Biological Definition of Microbial Populations. Cell, 178, 820-834.e14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2019.06.033 | A rapid and simple method for assessing and representing genome sequence relatedness | M Briand, M Bouzid, G Hunault, M Legeay, M Fischer-Le Saux, M Barret | <p>Coherent genomic groups are frequently used as a proxy for bacterial species delineation through computation of overall genome relatedness indices (OGRI). Average nucleotide identity (ANI) is a widely employed method for estimating relatedness ... |  | Bioinformatics, Metagenomics | B. Jesse Shapiro | Gavin Douglas | 2019-11-07 16:37:56 | View |

05 May 2021

A primer and discussion on DNA-based microbiome data and related bioinformatics analysesGavin M. Douglas and Morgan G. I. Langille https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/3dybgA hitchhiker’s guide to DNA-based microbiome analysisRecommended by Danny Ionescu based on reviews by Nicolas Pollet, Rafael Cuadrat and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Nicolas Pollet, Rafael Cuadrat and 1 anonymous reviewer

In the last two decades, microbial research in its different fields has been increasingly focusing on microbiome studies. These are defined as studies of complete assemblages of microorganisms in given environments and have been benefiting from increases in sequencing length, quality, and yield, coupled with ever-dropping prices per sequenced nucleotide. Alongside localized microbiome studies, several global collaborative efforts have emerged, including the Human Microbiome Project [1], the Earth Microbiome Project [2], the Extreme Microbiome Project, and MetaSUB [3]. Coupled with the development of sequencing technologies and the ever-increasing amount of data output, multiple standalone or online bioinformatic tools have been designed to analyze these data. Often these tools have been focusing on either of two main tasks: 1) Community analysis, providing information on the organisms present in the microbiome, or 2) Functionality, in the case of shotgun metagenomic data, providing information on the metabolic potential of the microbiome. Bridging between the two types of data, often extracted from the same dataset, is typically a daunting task that has been addressed by a handful of tools only. The extent of tools and approaches to analyze microbiome data is great and may be overwhelming to researchers new to microbiome or bioinformatic studies. In their paper “A primer and discussion on DNA-based microbiome data and related bioinformatics analyses”, Douglas and Langille [4] guide us through the different sequencing approaches useful for microbiome studies. alongside their advantages and caveats and a selection of tools to analyze these data, coupled with examples from their own field of research. Standing out in their primer-style review is the emphasis on the coupling between taxonomic/phylogenetic identification of the organisms and their functionality. This type of analysis, though highly important to understand the role of different microorganisms in an environment as well as to identify potential functional redundancy, is often not conducted. For this, the authors identify two approaches. The first, using shotgun metagenomics, has higher chances of attributing a function to the correct taxon. The second, using amplicon sequencing of marker genes, allows for a deeper coverage of the microbiome at a lower cost, and extrapolates the amplicon data to close relatives with a sequenced genome. As clearly stated, this approach makes the leap between taxonomy and functionality and has been shown to be erroneous in cases where the core genome of the bacterial genus or family does not encompass the functional diversity of the different included species. This practice was already common before the genomic era, but its accuracy is improving thanks to the increasing availability of sequenced reference genomes from cultures, environmentally picked single cells or metagenome-assembled genome. In addition to their description of standalone tools useful for linking taxonomy and functionality, one should mention the existence of online tools that may appeal to researchers who do not have access to adequate bioinformatics infrastructure. Among these are the Integrated Microbial Genomes and Microbiomes (IMG) from the Joint Genome Institute [5], KBase [6] and MG-RAST [7]. A second important point arising from this review is the need for standardization in microbiome data analyses and the complexity of achieving this. As Douglas and Langille [4] state, this has been previously addressed, highlighting the variability in results obtained with different tools. It is often the case that papers describing new bioinformatic tools display their superiority relative to existing alternatives, potentially misleading newcomers to the field that the newest tool is the best and only one to be used. This is often not the case, and while benchmarking against well-defined datasets serves as a powerful testing tool, “real-life” samples are often not comparable. Thus, as done here, future primer-like reviews should highlight possible cross-field caveats, encouraging researchers to employ and test several approaches and validate their results whenever possible. In summary, Douglas and Langille [4] offer both the novice and experienced researcher a detailed guide along the paths of microbiome data analysis, accompanied by informative background information, suggested tools with which analyses can be started, and an insightful view on where the field should be heading. References [1] Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Hamady M, Fraser-Liggett CM, Knight R, Gordon JI (2007) The Human Microbiome Project. Nature, 449, 804–810. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06244 [2] Gilbert JA, Jansson JK, Knight R (2014) The Earth Microbiome project: successes and aspirations. BMC Biology, 12, 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-014-0069-1 [3] Mason C, Afshinnekoo E, Ahsannudin S, Ghedin E, Read T, Fraser C, Dudley J, Hernandez M, Bowler C, Stolovitzky G, Chernonetz A, Gray A, Darling A, Burke C, Łabaj PP, Graf A, Noushmehr H, Moraes s., Dias-Neto E, Ugalde J, Guo Y, Zhou Y, Xie Z, Zheng D, Zhou H, Shi L, Zhu S, Tang A, Ivanković T, Siam R, Rascovan N, Richard H, Lafontaine I, Baron C, Nedunuri N, Prithiviraj B, Hyat S, Mehr S, Banihashemi K, Segata N, Suzuki H, Alpuche Aranda CM, Martinez J, Christopher Dada A, Osuolale O, Oguntoyinbo F, Dybwad M, Oliveira M, Fernandes A, Oliveira M, Fernandes A, Chatziefthimiou AD, Chaker S, Alexeev D, Chuvelev D, Kurilshikov A, Schuster S, Siwo GH, Jang S, Seo SC, Hwang SH, Ossowski S, Bezdan D, Udekwu K, Udekwu K, Lungjdahl PO, Nikolayeva O, Sezerman U, Kelly F, Metrustry S, Elhaik E, Gonnet G, Schriml L, Mongodin E, Huttenhower C, Gilbert J, Hernandez M, Vayndorf E, Blaser M, Schadt E, Eisen J, Beitel C, Hirschberg D, Schriml L, Mongodin E, The MetaSUB International Consortium (2016) The Metagenomics and Metadesign of the Subways and Urban Biomes (MetaSUB) International Consortium inaugural meeting report. Microbiome, 4, 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-016-0168-z [4] Douglas GM, Langille MGI (2021) A primer and discussion on DNA-based microbiome data and related bioinformatics analyses. OSF Preprints, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Genomics. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/3dybg [5] Chen I-MA, Markowitz VM, Chu K, Palaniappan K, Szeto E, Pillay M, Ratner A, Huang J, Andersen E, Huntemann M, Varghese N, Hadjithomas M, Tennessen K, Nielsen T, Ivanova NN, Kyrpides NC (2017) IMG/M: integrated genome and metagenome comparative data analysis system. Nucleic Acids Research, 45, D507–D516. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw929 [6] Arkin AP, Cottingham RW, Henry CS, Harris NL, Stevens RL, Maslov S, Dehal P, Ware D, Perez F, Canon S, Sneddon MW, Henderson ML, Riehl WJ, Murphy-Olson D, Chan SY, Kamimura RT, Kumari S, Drake MM, Brettin TS, Glass EM, Chivian D, Gunter D, Weston DJ, Allen BH, Baumohl J, Best AA, Bowen B, Brenner SE, Bun CC, Chandonia J-M, Chia J-M, Colasanti R, Conrad N, Davis JJ, Davison BH, DeJongh M, Devoid S, Dietrich E, Dubchak I, Edirisinghe JN, Fang G, Faria JP, Frybarger PM, Gerlach W, Gerstein M, Greiner A, Gurtowski J, Haun HL, He F, Jain R, Joachimiak MP, Keegan KP, Kondo S, Kumar V, Land ML, Meyer F, Mills M, Novichkov PS, Oh T, Olsen GJ, Olson R, Parrello B, Pasternak S, Pearson E, Poon SS, Price GA, Ramakrishnan S, Ranjan P, Ronald PC, Schatz MC, Seaver SMD, Shukla M, Sutormin RA, Syed MH, Thomason J, Tintle NL, Wang D, Xia F, Yoo H, Yoo S, Yu D (2018) KBase: The United States Department of Energy Systems Biology Knowledgebase. Nature Biotechnology, 36, 566–569. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.4163 [7] Wilke A, Bischof J, Gerlach W, Glass E, Harrison T, Keegan KP, Paczian T, Trimble WL, Bagchi S, Grama A, Chaterji S, Meyer F (2016) The MG-RAST metagenomics database and portal in 2015. Nucleic Acids Research, 44, D590–D594. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv1322 | A primer and discussion on DNA-based microbiome data and related bioinformatics analyses | Gavin M. Douglas and Morgan G. I. Langille | <p style="text-align: justify;">The past decade has seen an eruption of interest in profiling microbiomes through DNA sequencing. The resulting investigations have revealed myriad insights and attracted an influx of researchers to the research are... |  | Bioinformatics, Metagenomics | Danny Ionescu | 2021-02-17 00:26:46 | View |