Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields▼ | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

18 Feb 2021

Traces of transposable element in genome dark matter co-opted by flowering gene regulation networksAgnes Baud, Mariene Wan, Danielle Nouaud, Nicolas Francillonne, Dominique Anxolabehere, Hadi Quesneville https://doi.org/10.1101/547877Using small fragments to discover old TE remnants: the Duster approach empowers the TE detectionRecommended by Francois Sabot based on reviews by Josep Casacuberta and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Josep Casacuberta and 1 anonymous reviewer

Transposable elements are the raw material of the dark matter of the genome, the foundation of the next generation of genes and regulation networks". This sentence could be the essence of the paper of Baud et al. (2021). Transposable elements (TEs) are endogenous mobile genetic elements found in almost all genomes, which were discovered in 1948 by Barbara McClintock (awarded in 1983 the only unshared Medicine Nobel Prize so far). TEs are present everywhere, from a single isolated copy for some elements to more than millions for others, such as Alu. They are founders of major gene lineages (HET-A, TART and telomerases, RAG1/RAG2 proteins from mammals immune system; Diwash et al, 2017), and even of retroviruses (Xiong & Eickbush, 1988). However, most TEs appear as selfish elements that replicate, land in a new genomic region, then start to decay and finally disappear in the midst of the genome, turning into genomic ‘dark matter’ (Vitte et al, 2007). The mutations (single point, deletion, recombination, and so on) that occur during this slow death erase some of their most notable features and signature sequences, rendering them completely unrecognizable after a few million years. Numerous TE detection tools have tried to optimize their detection (Goerner-Potvin & Bourque, 2018), but further improvement is definitely challenging. This is what Baud et al. (2021) accomplished in their paper. They used a simple, elegant and efficient k-mer based approach to find small signatures that, when accumulated, allow identifying very old TEs. Using this method, called Duster, they improved the amount of annotated TEs in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana by 20%, pushing the part of this genome occupied by TEs up from 40 to almost 50%. They further observed that these very old Duster-specific TEs (i.e., TEs that are only detected by Duster) are, among other properties, close to genes (much more than recent TEs), not targeted by small RNA pathways, and highly associated with conserved regions across the rosid family. In addition, they are highly associated with flowering or stress response genes, and may be involved through exaptation in the evolution of responses to environmental changes. TEs are not just selfish elements: more and more studies have shown their key role in the evolution of their hosts, and tools such as Duster will help us better understand their impact. References Baud, A., Wan, M., Nouaud, D., Francillonne, N., Anxolabéhère, D. and Quesneville, H. (2021). Traces of transposable elements in genome dark matter co-opted by flowering gene regulation networks. bioRxiv, 547877, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Genomics.doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/547877 | Traces of transposable element in genome dark matter co-opted by flowering gene regulation networks | Agnes Baud, Mariene Wan, Danielle Nouaud, Nicolas Francillonne, Dominique Anxolabehere, Hadi Quesneville | <p>Transposable elements (TEs) are mobile, repetitive DNA sequences that make the largest contribution to genome bulk. They thus contribute to the so-called 'dark matter of the genome', the part of the genome in which nothing is immediately recogn... |  | Bioinformatics, Evolutionary genomics, Functional genomics, Plants, Structural genomics, Viruses and transposable elements | Francois Sabot | Anonymous, Josep Casacuberta | 2020-04-07 17:12:12 | View |

23 Sep 2022

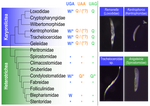

MATEdb, a data repository of high-quality metazoan transcriptome assemblies to accelerate phylogenomic studiesRosa Fernandez, Vanina Tonzo, Carolina Simon Guerrero, Jesus Lozano-Fernandez, Gemma I Martinez-Redondo, Pau Balart-Garcia, Leandro Aristide, Klara Eleftheriadi, Carlos Vargas-Chavez https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.18.500182MATEdb: a new phylogenomic-driven database for MetazoaRecommended by Samuel Abalde based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

The development (and standardization) of high-throughput sequencing techniques has revolutionized evolutionary biology, to the point that we almost see as normal fine-detail studies of genome architecture evolution (Robert et al., 2022), adaptation to new habitats (Rahi et al., 2019), or the development of key evolutionary novelties (Hilgers et al., 2018), to name three examples. One of the fields that has benefited the most is phylogenomics, i.e. the use of genome-wide data for inferring the evolutionary relationships among organisms. Dealing with such amount of data, however, has come with important analytical and computational challenges. Likewise, although the steady generation of genomic data from virtually any organism opens exciting opportunities for comparative analyses, it also creates a sort of “information fog”, where it is hard to find the most appropriate and/or the higher quality data. I have personally experienced this not so long ago, when I had to spend several weeks selecting the most complete transcriptomes from several phyla, moving back and forth between the NCBI SRA repository and the relevant literature. In an attempt to deal with this issue, some research labs have committed their time and resources to the generation of taxa- and topic-specific databases (Lathe et al., 2008), such as MolluscDB (Liu et al., 2021), focused on mollusk genomics, or EukProt (Richter et al., 2022), a protein repository representing the diversity of eukaryotes. A new database that promises to become an important resource in the near future is MATEdb (Fernández et al., 2022), a repository of high-quality genomic data from Metazoa. MATEdb has been developed from publicly available and newly generated transcriptomes and genomes, prioritizing quality over quantity. Upon download, the user has access to both raw data and the related datasets: assemblies, several quality metrics, the set of inferred protein-coding genes, and their annotation. Although it is clear to me that this repository has been created with phylogenomic analyses in mind, I see how it could be generalized to other related problems such as analyses of gene content or evolution of specific gene families. In my opinion, the main strengths of MATEdb are threefold:

On a negative note, I see two main drawbacks. First, as of today (September 16th, 2022) this database is in an early stage and it still needs to incorporate a lot of animal groups. This has been discussed during the revision process and the authors are already working on it, so it is only a matter of time until all major taxa are represented. Second, there is a scalability issue. In its current format it is not possible to select the taxa of interest and the full database has to be downloaded, which will become more and more difficult as it grows. Nonetheless, with the appropriate resources it would be easy to find a better solution. There are plenty of examples that could serve as inspiration, so I hope this does not become a big problem in the future. Altogether, I and the researchers that participated in the revision process believe that MATEdb has the potential to become an important and valuable addition to the metazoan phylogenomics community. Personally, I wish it was available just a few months ago, it would have saved me so much time. References Fernández R, Tonzo V, Guerrero CS, Lozano-Fernandez J, Martínez-Redondo GI, Balart-García P, Aristide L, Eleftheriadi K, Vargas-Chávez C (2022) MATEdb, a data repository of high-quality metazoan transcriptome assemblies to accelerate phylogenomic studies. bioRxiv, 2022.07.18.500182, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.18.500182 Hilgers L, Hartmann S, Hofreiter M, von Rintelen T (2018) Novel Genes, Ancient Genes, and Gene Co-Option Contributed to the Genetic Basis of the Radula, a Molluscan Innovation. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 35, 1638–1652. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy052 Lathe W, Williams J, Mangan M, Karolchik, D (2008). Genomic data resources: challenges and promises. Nature Education, 1(3), 2. Liu F, Li Y, Yu H, Zhang L, Hu J, Bao Z, Wang S (2021) MolluscDB: an integrated functional and evolutionary genomics database for the hyper-diverse animal phylum Mollusca. Nucleic Acids Research, 49, D988–D997. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa918 Rahi ML, Mather PB, Ezaz T, Hurwood DA (2019) The Molecular Basis of Freshwater Adaptation in Prawns: Insights from Comparative Transcriptomics of Three Macrobrachium Species. Genome Biology and Evolution, 11, 1002–1018. https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evz045 Richter DJ, Berney C, Strassert JFH, Poh Y-P, Herman EK, Muñoz-Gómez SA, Wideman JG, Burki F, Vargas C de (2022) EukProt: A database of genome-scale predicted proteins across the diversity of eukaryotes. bioRxiv, 2020.06.30.180687, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.30.180687 Robert NSM, Sarigol F, Zimmermann B, Meyer A, Voolstra CR, Simakov O (2022) Emergence of distinct syntenic density regimes is associated with early metazoan genomic transitions. BMC Genomics, 23, 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-022-08304-2 | MATEdb, a data repository of high-quality metazoan transcriptome assemblies to accelerate phylogenomic studies | Rosa Fernandez, Vanina Tonzo, Carolina Simon Guerrero, Jesus Lozano-Fernandez, Gemma I Martinez-Redondo, Pau Balart-Garcia, Leandro Aristide, Klara Eleftheriadi, Carlos Vargas-Chavez | <p style="text-align: justify;">With the advent of high throughput sequencing, the amount of genomic data available for animals (Metazoa) species has bloomed over the last decade, especially from transcriptomes due to lower sequencing costs and ea... |  | Bioinformatics, Evolutionary genomics, Functional genomics | Samuel Abalde | 2022-07-20 07:30:39 | View | |

19 Jul 2021

TransPi - a comprehensive TRanscriptome ANalysiS PIpeline for de novo transcriptome assemblyRamon E Rivera-Vicens, Catalina Garcia-Escudero, Nicola Conci, Michael Eitel, Gert Wörheide https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.18.431773TransPI: A balancing act between transcriptome assemblersRecommended by Oleg Simakov based on reviews by Gustavo Sanchez and Juan Daniel Montenegro CabreraEver since the introduction of the first widely usable assemblers for transcriptomic reads (Huang and Madan 1999; Schulz et al. 2012; Simpson et al. 2009; Trapnell et al. 2010, and many more), it has been a technical challenge to compare different methods and to choose the “right” or “best” assembly. It took years until the first widely accepted set of benchmarks beyond raw statistical evaluation became available (e.g., Parra, Bradnam, and Korf 2007; Simão et al. 2015). However, an approach to find the right balance between the number of transcripts or isoforms vs. evolutionary completeness measures has been lacking. This has been particularly pronounced in the field of non-model organisms (i.e., wild species that lack a genomic reference). Often, studies in this area employed only one set of assembly tools (the most often used to this day being Trinity, Haas et al. 2013; Grabherr et al. 2011). While it was relatively straightforward to obtain an initial assembly, its validation, annotation, as well its application to the particular purpose that the study was designed for (phylogenetics, differential gene expression, etc) lacked a clear workflow. This led to many studies using a custom set of tools with ensuing various degrees of reproducibility. TransPi (Rivera-Vicéns et al. 2021) fills this gap by first employing a meta approach using several available transcriptome assemblers and algorithms to produce a combined and reduced transcriptome assembly, then validating and annotating the resulting transcriptome. Notably, TransPI performs an extensive analysis/detection of chimeric transcripts, the results of which show that this new tool often produces fewer misassemblies compared to Trinity. TransPI not only generates a final report that includes the most important plots (in clickable/zoomable format) but also stores all relevant intermediate files, allowing advanced users to take a deeper look and/or experiment with different settings. As running TransPi is largely automated (including its installation via several popular package managers), it is very user-friendly and is likely to become the new "gold standard" for transcriptome analyses, especially of non-model organisms. References Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, Amit I, Adiconis X, Fan L, Raychowdhury R, Zeng Q, Chen Z, Mauceli E, Hacohen N, Gnirke A, Rhind N, di Palma F, Birren BW, Nusbaum C, Lindblad-Toh K, Friedman N, Regev A (2011) Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nature Biotechnology, 29, 644–652. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.1883 Haas BJ, Papanicolaou A, Yassour M, Grabherr M, Blood PD, Bowden J, Couger MB, Eccles D, Li B, Lieber M, MacManes MD, Ott M, Orvis J, Pochet N, Strozzi F, Weeks N, Westerman R, William T, Dewey CN, Henschel R, LeDuc RD, Friedman N, Regev A (2013) De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nature Protocols, 8, 1494–1512. https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2013.084 Huang X, Madan A (1999) CAP3: A DNA Sequence Assembly Program. Genome Research, 9, 868–877. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.9.9.868 Parra G, Bradnam K, Korf I (2007) CEGMA: a pipeline to accurately annotate core genes in eukaryotic genomes. Bioinformatics, 23, 1061–1067. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btm071 Rivera-Vicéns RE, Garcia-Escudero CA, Conci N, Eitel M, Wörheide G (2021) TransPi – a comprehensive TRanscriptome ANalysiS PIpeline for de novo transcriptome assembly. bioRxiv, 2021.02.18.431773, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.18.431773 Schulz MH, Zerbino DR, Vingron M, Birney E (2012) Oases: robust de novo RNA-seq assembly across the dynamic range of expression levels. Bioinformatics, 28, 1086–1092. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bts094 Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM (2015) BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics, 31, 3210–3212. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351 Simpson JT, Wong K, Jackman SD, Schein JE, Jones SJM, Birol İ (2009) ABySS: A parallel assembler for short read sequence data. Genome Research, 19, 1117–1123. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.089532.108 Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, Salzberg SL, Wold BJ, Pachter L (2010) Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nature Biotechnology, 28, 511–515. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.1621 | TransPi - a comprehensive TRanscriptome ANalysiS PIpeline for de novo transcriptome assembly | Ramon E Rivera-Vicens, Catalina Garcia-Escudero, Nicola Conci, Michael Eitel, Gert Wörheide | <p style="text-align: justify;">The use of RNA-Seq data and the generation of de novo transcriptome assemblies have been pivotal for studies in ecology and evolution. This is distinctly true for non-model organisms, where no genome information is ... |  | Bioinformatics, Evolutionary genomics | Oleg Simakov | 2021-02-18 20:56:08 | View | |

06 May 2022

A deep dive into genome assemblies of non-vertebrate animalsNadège Guiglielmoni, Ramón Rivera-Vicéns, Romain Koszul, Jean-François Flot https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202111.0170.v3Diving, and even digging, into the wild jungle of annotation pathways for non-vertebrate animalsRecommended by Francois Sabot based on reviews by Yann Bourgeois, Cécile Monat, Valentina Peona and Benjamin Istace based on reviews by Yann Bourgeois, Cécile Monat, Valentina Peona and Benjamin Istace

In their paper, Guiglielmoni et al. propose we pick up our snorkels and palms and take "A deep dive into genome assemblies of non-vertebrate animals" (1). Indeed, while numerous assembly-related tools were developed and tested for human genomes (or at least vertebrates such as mice), very few were tested on non-vertebrate animals so far. Moreover, most of the benchmarks are aimed at raw assembly tools, and very few offer a guide from raw reads to an almost finished assembly, including quality control and phasing. This huge and exhaustive review starts with an overview of the current sequencing technologies, followed by the theory of the different approaches for assembly and their implementation. For each approach, the authors present some of the most representative tools, as well as the limits of the approach. The authors additionally present all the steps required to obtain an almost complete assembly at a chromosome-scale, with all the different technologies currently available for scaffolding, QC, and phasing, and the way these tools can be applied to non-vertebrates animals. Finally, they propose some useful advice on the choice of the different approaches (but not always tools, see below), and advocate for a robust genome database with all information on the way the assembly was obtained. This review is a very complete one for now and is a very good starting point for any student or scientist interested to start working on genome assembly, from either model or non-model organisms. However, the authors do not provide a list of tools or a benchmark of them as a recommendation. Why? Because such a proposal may be obsolete in less than a year.... Indeed, with the explosion of the 3rd generation of sequencing technology, assembly tools (from different steps) are constantly evolving, and their relative performance increases on a monthly basis. In addition, some tools are really efficient at the time of a review or of an article, but are not further developed later on, and thus will not evolve with the technology. We have all seen it with wonderful tools such as Chiron (2) or TopHat (3), which were very promising ones, but cannot be developed further due to the stop of the project, the end of the contract of the post-doc in charge of the development, or the decision of the developer to switch to another paradigm. Such advice would, therefore, need to be constantly updated. Thus, the manuscript from Guiglielmoni et al will be an almost intemporal one (up to the next sequencing revolution at last), and as they advocated for a more informed genome database, I think we should consider a rolling benchmarking system (tools, genome and sequence dataset) allowing to keep the performance of the tools up-to-date, and to propose the best set of assembly tools for a given type of genome. References 1. Guiglielmoni N, Rivera-Vicéns R, Koszul R, Flot J-F (2022) A Deep Dive into Genome Assemblies of Non-vertebrate Animals. Preprints, 2021110170, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202111.0170 2. Teng H, Cao MD, Hall MB, Duarte T, Wang S, Coin LJM (2018) Chiron: translating nanopore raw signal directly into nucleotide sequence using deep learning. GigaScience, 7, giy037. https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giy037 3. Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzberg SL (2009) TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics, 25, 1105–1111. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp120 | A deep dive into genome assemblies of non-vertebrate animals | Nadège Guiglielmoni, Ramón Rivera-Vicéns, Romain Koszul, Jean-François Flot | <p style="text-align: justify;">Non-vertebrate species represent about ∼95% of known metazoan (animal) diversity. They remain to this day relatively unexplored genetically, but understanding their genome structure and function is pivotal for expan... |  | Bioinformatics, Evolutionary genomics | Francois Sabot | Valentina Peona, Benjamin Istace, Cécile Monat, Yann Bourgeois | 2021-11-10 17:47:31 | View |

13 Jul 2022

Karyorelict ciliates use an ambiguous genetic code with context-dependent stop/sense codonsBrandon Kwee Boon Seah, Aditi Singh, Estienne Carl Swart https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.12.488043An accident frozen in time: the ambiguous stop/sense genetic code of karyorelict ciliatesRecommended by Iker Irisarri based on reviews by Vittorio Boscaro and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Vittorio Boscaro and 2 anonymous reviewers

Several variations of the “universal” genetic code are known. Among the most striking are those where a codon can either encode for an amino acid or a stop signal depending on the context. Such ambiguous codes are known to have evolved in eukaryotes multiple times independently, particularly in ciliates – eight different codes have so far been discovered (1). We generally view such genetic codes are rare ‘variants’ of the standard code restricted to single species or strains, but this might as well reflect a lack of study of closely related species. In this study, Seah and co-authors (2) explore the possibility of codon reassignment in karyorelict ciliates closely related to Parduczia sp., which has been shown to contain an ambiguous genetic code (1). Here, single-cell transcriptomics are used, along with similar available data, to explore the possibility of codon reassignment across the diversity of Karyorelictea (four out of the six recognized families). Codon reassignments were inferred from their frequencies within conserved Pfam (3) protein domains, whereas stop codons were inferred from full-length transcripts with intact 3’-UTRs. Results show the reassignment of UAA and UAG stop codons to code for glutamine (Q) and the reassignment of the UGA stop codon into tryptophan (W). This occurs only within the coding sequences, whereas the end of transcription is marked by UGA as the main stop codon, and to a lesser extent by UAA. In agreement with a previous model proposed that explains the functioning of ambiguous codes (1,4), the authors observe a depletion of in-frame UGAs before the UGA codon that indicates the stop, thus avoiding premature termination of transcription. The inferred codon reassignments occur in all studied karyorelicts, including the previously studied Parduczia sp. Despite the overall clear picture, some questions remain. Data for two out of six main karyorelict lineages are so far absent and the available data for Cryptopharyngidae was inconclusive; the phylogenetic affinities of Cryptopharyngidae have also been questioned (5). This indicates the need for further study of this interesting group of organisms. As nicely discussed by the authors, experimental evidence could further strengthen the conclusions of this paper, including ribosome profiling, mass spectrometry – as done for Condylostoma (1) – or even direct genetic manipulation. The uniformity of the ambiguous genetic code across karyorelicts might at first seem dull, but when viewed in a phylogenetic context character distribution strongly suggest that this genetic code has an ancient origin in the karyorelict ancestor ~455 Ma in the Proterozoic (6). This ambiguous code is also not a rarity of some obscure species, but it is shared by ciliates that are very diverse and ecologically important. The origin of the karyorelict code is also intriguing. Adaptive arguments suggest that it could confer robustness to mutations causing premature stop codons. However, we lack evidence for ambiguous codes being linked to specific habitats of lifestyles that could account for it. Instead, the authors favor the neutral view of an ancient “frozen accident”, fixed stochastically simply because it did not pose a significant selective disadvantage. Once a stop codon is reassigned to an amino acid, it is increasingly difficult to revert this without the deleterious effect of prematurely terminating translation. At the end, the origin of the genetic code itself is thought to be a frozen accident too (7). References 1. Swart EC, Serra V, Petroni G, Nowacki M. Genetic codes with no dedicated stop codon: Context-dependent translation termination. Cell 2016;166: 691–702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.020 2. Seah BKB, Singh A, Swart EC (2022) Karyorelict ciliates use an ambiguous genetic code with context-dependent stop/sense codons. bioRxiv, 2022.04.12.488043. ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.12.488043 3. Mistry J, Chuguransky S, Williams L, Qureshi M, Salazar GA, Sonnhammer ELL, Tosatto SCE, Paladin L, Raj S, Richardson LJ, Finn RD, Bateman A. Pfam: The protein families database in 2021, Nuc Acids Res 2020;49: D412-D419. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa913 4. Alkalaeva E, Mikhailova T. Reassigning stop codons via translation termination: How a few eukaryotes broke the dogma. Bioessays. 2017;39. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.201600213 5. Xu Y, Li J, Song W, Warren A. Phylogeny and establishment of a new ciliate family, Wilbertomorphidae fam. nov. (Ciliophora, Karyorelictea), a highly specialized taxon represented by Wilbertomorpha colpoda gen. nov., spec. nov. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2013;60: 480–489. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeu.12055 6. Fernandes NM, Schrago CG. A multigene timescale and diversification dynamics of Ciliophora evolution. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2019;139: 106521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2019.106521 7. Crick FH. The origin of the genetic code. J Mol Biol. 1968;38: 367–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-2836(68)90392-6 | Karyorelict ciliates use an ambiguous genetic code with context-dependent stop/sense codons | Brandon Kwee Boon Seah, Aditi Singh, Estienne Carl Swart | <p style="text-align: justify;">In ambiguous stop/sense genetic codes, the stop codon(s) not only terminate translation but can also encode amino acids. Such codes have evolved at least four times in eukaryotes, twice among ciliates (<em>Condylost... |  | Bioinformatics, Evolutionary genomics | Iker Irisarri | 2022-05-02 11:06:10 | View | |

15 Sep 2022

EukProt: A database of genome-scale predicted proteins across the diversity of eukaryotesDaniel J. Richter, Cédric Berney, Jürgen F. H. Strassert, Yu-Ping Poh, Emily K. Herman, Sergio A. Muñoz-Gómez, Jeremy G. Wideman, Fabien Burki, Colomban de Vargas https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.30.180687EukProt enables reproducible Eukaryota-wide protein sequence analysesRecommended by Gavin Douglas based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Comparative genomics is a general approach for understanding how genomes differ, which can be considered from many angles. For instance, this approach can delineate how gene content varies across organisms, which can lead to novel hypotheses regarding what those organisms do. It also enables investigations into the sequence-level divergence of orthologous DNA, which can provide insight into how evolutionary forces differentially shape genome content and structure across lineages. Burki F, Roger AJ, Brown MW, Simpson AGB (2020) The New Tree of Eukaryotes. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 35, 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2019.08.008 Richter DJ, Berney C, Strassert JFH, Poh Y-P, Herman EK, Muñoz-Gómez SA, Wideman JG, Burki F, Vargas C de (2022) EukProt: A database of genome-scale predicted proteins across the diversity of eukaryotes. bioRxiv, 2020.06.30.180687, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.30.180687 Wilkinson MD, Dumontier M, Aalbersberg IjJ, Appleton G, Axton M, Baak A, Blomberg N, Boiten J-W, da Silva Santos LB, Bourne PE, Bouwman J, Brookes AJ, Clark T, Crosas M, Dillo I, Dumon O, Edmunds S, Evelo CT, Finkers R, Gonzalez-Beltran A, Gray AJG, Groth P, Goble C, Grethe JS, Heringa J, ’t Hoen PAC, Hooft R, Kuhn T, Kok R, Kok J, Lusher SJ, Martone ME, Mons A, Packer AL, Persson B, Rocca-Serra P, Roos M, van Schaik R, Sansone S-A, Schultes E, Sengstag T, Slater T, Strawn G, Swertz MA, Thompson M, van der Lei J, van Mulligen E, Velterop J, Waagmeester A, Wittenburg P, Wolstencroft K, Zhao J, Mons B (2016) The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data, 3, 160018. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18 | EukProt: A database of genome-scale predicted proteins across the diversity of eukaryotes | Daniel J. Richter, Cédric Berney, Jürgen F. H. Strassert, Yu-Ping Poh, Emily K. Herman, Sergio A. Muñoz-Gómez, Jeremy G. Wideman, Fabien Burki, Colomban de Vargas | <p style="text-align: justify;">EukProt is a database of published and publicly available predicted protein sets selected to represent the breadth of eukaryotic diversity, currently including 993 species from all major supergroups as well as orpha... |  | Bioinformatics, Evolutionary genomics | Gavin Douglas | 2022-06-08 14:19:28 | View | |

11 Sep 2023

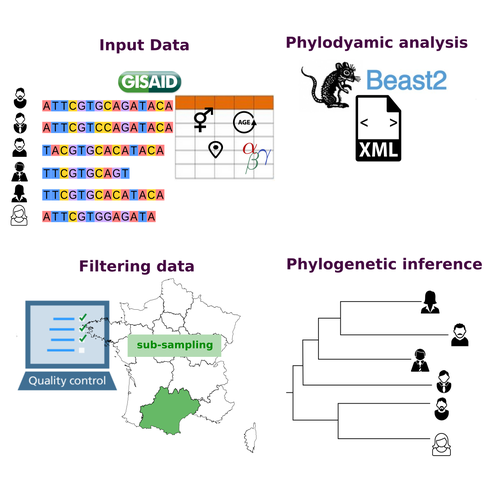

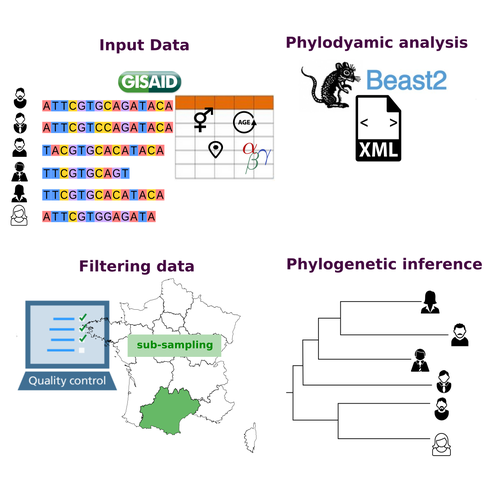

COVFlow: phylodynamics analyses of viruses from selected SARS-CoV-2 genome sequencesGonché Danesh, Corentin Boennec, Laura Verdurme, Mathilde Roussel, Sabine Trombert-Paolantoni, Benoit Visseaux, Stephanie Haim-Boukobza, Samuel Alizon https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.17.496544A pipeline to select SARS-CoV-2 sequences for reliable phylodynamic analysesRecommended by Emmanuelle Lerat based on reviews by Gabriel Wallau and Bastien BoussauPhylodynamic approaches enable viral genetic variation to be tracked over time, providing insight into pathogen phylogenetic relationships and epidemiological dynamics. These are important methods for monitoring viral spread, and identifying important parameters such as transmission rate, geographic origin and duration of infection [1]. This knowledge makes it possible to adjust public health measures in real-time and was important in the case of the COVID-19 pandemic [2]. However, these approaches can be complicated to use when combining a very large number of sequences. This was particularly true during the COVID-19 pandemic, when sequencing data representing millions of entire viral genomes was generated, with associated metadata enabling their precise identification. Danesh et al. [3] present a bioinformatics pipeline, CovFlow, for selecting relevant sequences according to user-defined criteria to produce files that can be used directly for phylodynamic analyses. The selection of sequences first involves a quality filter on the size of the sequences and the absence of unresolved bases before being able to make choices based on the associated metadata. Once the sequences are selected, they are aligned and a time-scaled phylogenetic tree is inferred. An output file in a format directly usable by BEAST 2 [4] is finally generated. To illustrate the use of the pipeline, Danesh et al. [3] present an analysis of the Delta variant in two regions of France. They observed a delay in the start of the epidemic depending on the region. In addition, they identified genetic variation linked to the start of the school year and the extension of vaccination, as well as the arrival of a new variant. This tool will be of major interest to researchers analysing SARS-CoV-2 sequencing data, and a number of future developments are planned by the authors. References [1] Baele G, Dellicour S, Suchard MA, Lemey P, Vrancken B. 2018. Recent advances in computational phylodynamics. Curr Opin Virol. 31:24-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coviro.2018.08.009 [2] Attwood SW, Hill SC, Aanensen DM, Connor TR, Pybus OG. 2022. Phylogenetic and phylodynamic approaches to understanding and combating the early SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Nat Rev Genet. 23:547-562. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-022-00483-8 [3] Danesh G, Boennec C, Verdurme L, Roussel M, Trombert-Paolantoni S, Visseaux B, Haim-Boukobza S, Alizon S. 2023. COVFlow: phylodynamics analyses of viruses from selected SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences. bioRxiv, ver. 7 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.17.496544 [4] Bouckaert R, Heled J, Kühnert D, Vaughan T, Wu C-H et al. 2014. BEAST 2: a software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLoS Comput Biol 10: e1003537. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003537 | COVFlow: phylodynamics analyses of viruses from selected SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences | Gonché Danesh, Corentin Boennec, Laura Verdurme, Mathilde Roussel, Sabine Trombert-Paolantoni, Benoit Visseaux, Stephanie Haim-Boukobza, Samuel Alizon | <p style="text-align: justify;">Phylodynamic analyses generate important and timely data to optimise public health response to SARS-CoV-2 outbreaks and epidemics. However, their implementation is hampered by the massive amount of sequence data and... |  | Bioinformatics, Evolutionary genomics | Emmanuelle Lerat | 2022-12-12 09:04:01 | View | |

14 Sep 2023

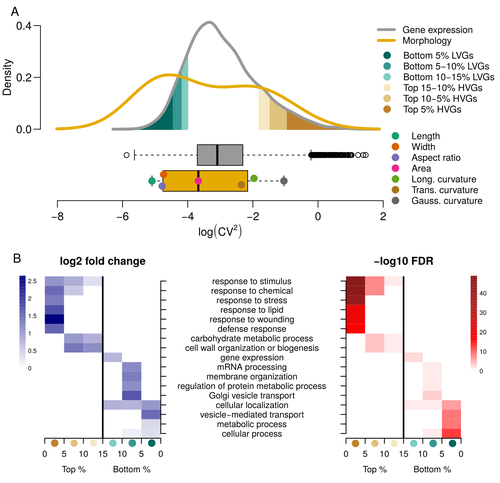

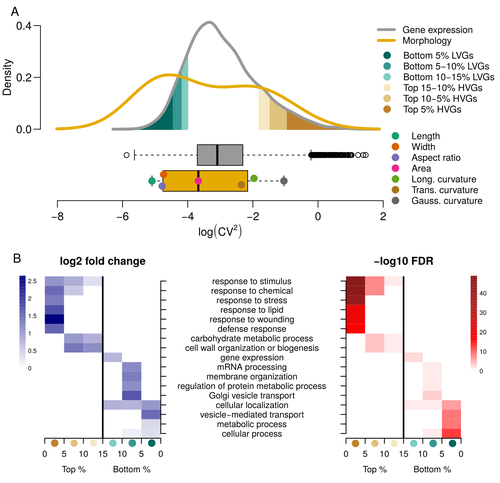

Expression of cell-wall related genes is highly variable and correlates with sepal morphologyDiego A. Hartasánchez, Annamaria Kiss, Virginie Battu, Charline Soraru, Abigail Delgado-Vaquera, Florian Massinon, Marina Brasó-Vives, Corentin Mollier, Marie-Laure Martin-Magniette, Arezki Boudaoud, Françoise Monéger https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.26.489498The same but different: How small scale hidden variations can have large effectsRecommended by Francois Sabot based on reviews by Sandra Corjito and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Sandra Corjito and 1 anonymous reviewer

For ages, we considered only single genes, or just a few, in order to understand the relationship between phenotype and genotype in response to environmental challenges. Recently, the use of meaningful groups of genes, e.g. gene regulatory networks, or modules of co-expression, allowed scientists to have a larger view of gene regulation. However, all these findings were based on contrasted genotypes, e.g. between wild-types and mutants, as the implicit assumption often made is that there is little transcriptomic variability within the same genotype context. Hartasànchez and collaborators (2023) decided to challenge both views: they used a single genotype instead of two, the famous A. thaliana Col0, and numerous plants, and considered whole gene networks related to sepal morphology and its variations. They used a clever approach, combining high-level phenotyping and gene expression to better understand phenomena and regulations underlying sepal morphologies. Using multiple controls, they showed that basic variations in the expression of genes related to the cell wall regulation, as well as the ones involved in chloroplast metabolism, influenced the global transcriptomic pattern observed in sepal while being in near-identical genetic background and controlling for all other experimental conditions. The paper of Hartasànchez et al. is thus a tremendous call for humility in biology, as we saw in their work that we just understand the gross machinery. However, the Devil is in the details: understanding those very small variations that may have a large influence on phenotypes, and thus on local adaptation to environmental challenges, is of great importance in these times of climatic changes. References Hartasánchez DA, Kiss A, Battu V, Soraru C, Delgado-Vaquera A, Massinon F, Brasó-Vives M, Mollier C, Martin-Magniette M-L, Boudaoud A, Monéger F. 2023. Expression of cell-wall related genes is highly variable and correlates with sepal morphology. bioRxiv, ver. 4, peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.26.489498 | Expression of cell-wall related genes is highly variable and correlates with sepal morphology | Diego A. Hartasánchez, Annamaria Kiss, Virginie Battu, Charline Soraru, Abigail Delgado-Vaquera, Florian Massinon, Marina Brasó-Vives, Corentin Mollier, Marie-Laure Martin-Magniette, Arezki Boudaoud, Françoise Monéger | <p style="text-align: justify;">Control of organ morphology is a fundamental feature of living organisms. There is, however, observable variation in organ size and shape within a given genotype. Taking the sepal of Arabidopsis as a model, we inves... |  | Bioinformatics, Epigenomics, Plants | Francois Sabot | 2023-03-14 19:10:15 | View | |

16 Dec 2022

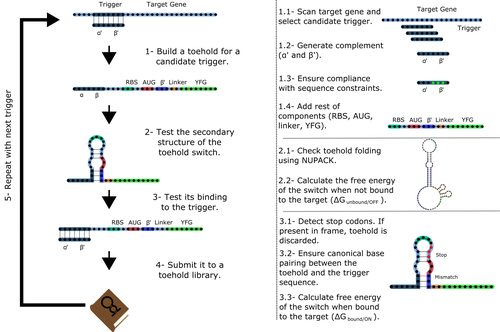

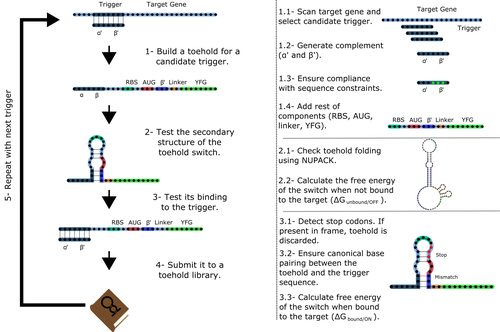

Toeholder: a Software for Automated Design and In Silico Validation of Toehold RiboswitchesAngel F. Cisneros, François D. Rouleau, Carla Bautista, Pascale Lemieux, Nathan Dumont-Leblond https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.09.467922A novel approach for engineering biological systems by interfacing computer science with synthetic biologyRecommended by Sahar Melamed based on reviews by Wim Wranken and 1 anonymous reviewerBiological systems depend on finely tuned interactions of their components. Thus, regulating these components is critical for the system's functionality. In prokaryotic cells, riboswitches are regulatory elements controlling transcription or translation. Riboswitches are RNA molecules that are usually located in the 5′-untranslated region of protein-coding genes. They generate secondary structures leading to the regulation of the expression of the downstream protein-coding gene (Kavita and Breaker, 2022). Riboswitches are very versatile and can bind a wide range of small molecules; in many cases, these are metabolic byproducts from the gene’s enzymatic or signaling pathway. Their versatility and abundance in many species make them attractive for synthetic biological circuits. One class that has been drawing the attention of synthetic biologists is toehold switches (Ekdahl et al., 2022; Green et al., 2014). These are single-stranded RNA molecules harboring the necessary elements for translation initiation of the downstream gene: a ribosome-binding site and a start codon. Conformation change of toehold switches is triggered by an RNA molecule, which enables translation. To exploit the most out of toehold switches, automation of their design would be highly advantageous. Cisneros and colleagues (Cisneros et al., 2022) developed a tool, “Toeholder”, that automates the design of toehold switches and performs in silico tests to select switch candidates for a target gene. Toeholder is an open-source tool that provides a comprehensive and automated workflow for the design of toehold switches. While web tools have been developed for designing toehold switches (To et al., 2018), Toeholder represents an intriguing approach to engineering biological systems by coupling synthetic biology with computational biology. Using molecular dynamics simulations, it identified the positions in the toehold switch where hydrogen bonds fluctuate the most. Identifying these regions holds great potential for modifications when refining the design of the riboswitches. To be effective, toehold switches should provide a strong ON signal and a weak OFF signal in the presence or the absence of a target, respectively. Toeholder nicely ranks the candidate toehold switches based on experimental evidence that correlates with toehold performance (based on good ON/OFF ratios). Riboswitches are highly appealing for a broad range of applications, including pharmaceutical and medical purposes (Blount and Breaker, 2006; Giarimoglou et al., 2022; Tickner and Farzan, 2021), thanks to their adaptability and inexpensiveness. The Toeholder tool developed by Cisneros and colleagues is expected to promote the implementation of toehold switches into these various applications. References Blount KF, Breaker RR (2006) Riboswitches as antibacterial drug targets. Nature Biotechnology, 24, 1558–1564. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt1268 Cisneros AF, Rouleau FD, Bautista C, Lemieux P, Dumont-Leblond N, ULaval 2019 T iGEM (2022) Toeholder: a Software for Automated Design and In Silico Validation of Toehold Riboswitches. bioRxiv, 2021.11.09.467922, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.09.467922 Ekdahl AM, Rojano-Nisimura AM, Contreras LM (2022) Engineering Toehold-Mediated Switches for Native RNA Detection and Regulation in Bacteria. Journal of Molecular Biology, 434, 167689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2022.167689 Giarimoglou N, Kouvela A, Maniatis A, Papakyriakou A, Zhang J, Stamatopoulou V, Stathopoulos C (2022) A Riboswitch-Driven Era of New Antibacterials. Antibiotics, 11, 1243. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11091243 Green AA, Silver PA, Collins JJ, Yin P (2014) Toehold Switches: De-Novo-Designed Regulators of Gene Expression. Cell, 159, 925–939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.002 Kavita K, Breaker RR (2022) Discovering riboswitches: the past and the future. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2022.08.009 Tickner ZJ, Farzan M (2021) Riboswitches for Controlled Expression of Therapeutic Transgenes Delivered by Adeno-Associated Viral Vectors. Pharmaceuticals, 14, 554. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14060554 To AC-Y, Chu DH-T, Wang AR, Li FC-Y, Chiu AW-O, Gao DY, Choi CHJ, Kong S-K, Chan T-F, Chan K-M, Yip KY (2018) A comprehensive web tool for toehold switch design. Bioinformatics, 34, 2862–2864. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty216 | Toeholder: a Software for Automated Design and In Silico Validation of Toehold Riboswitches | Angel F. Cisneros, François D. Rouleau, Carla Bautista, Pascale Lemieux, Nathan Dumont-Leblond | <p>Abstract: Synthetic biology aims to engineer biological circuits, which often involve gene expression. A particularly promising group of regulatory elements are riboswitches because of their versatility with respect to their targets, but e... |  | Bioinformatics | Sahar Melamed | 2022-02-16 14:40:13 | View | |

18 Jul 2022

CulebrONT: a streamlined long reads multi-assembler pipeline for prokaryotic and eukaryotic genomesJulie Orjuela, Aurore Comte, Sébastien Ravel, Florian Charriat, Tram Vi, Francois Sabot, Sébastien Cunnac https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.19.452922A flexible and reproducible pipeline for long-read assembly and evaluationRecommended by Raúl Castanera based on reviews by Benjamin Istace and Valentine MurigneuxThird-generation sequencing has revolutionised de novo genome assembly. Thanks to this technology, genome reference sequences have evolved from fragmented drafts to gapless, telomere-to-telomere genome assemblies. Long reads produced by Oxford Nanopore and PacBio technologies can span structural variants and resolve complex repetitive regions such as centromeres, unlocking previously inaccessible genomic information. Nowadays, many research groups can afford to sequence the genome of their working model using long reads. Nevertheless, genome assembly poses a significant computational challenge. Read length, quality, coverage and genomic features such as repeat content can affect assembly contiguity, accuracy, and completeness in almost unpredictable ways. Consequently, there is no best universal software or protocol for this task. Producing a high-quality assembly requires chaining several tools into pipelines and performing extensive comparisons between the assemblies obtained by different tool combinations to decide which one is the best. This task can be extremely challenging, as the number of tools available rises very rapidly, and thorough benchmarks cannot be updated and published at such a fast pace. In their paper, Orjuela and collaborators present CulebrONT [1], a universal pipeline that greatly contributes to overcoming these challenges and facilitates long-read genome assembly for all taxonomic groups. CulebrONT incorporates six commonly used assemblers and allows to perform assembly, circularization (if needed), polishing, and evaluation in a simple framework. One important aspect of CulebrONT is its modularity, which allows the activation or deactivation of specific tools, giving great flexibility to the user. Nevertheless, possibly the best feature of CulebrONT is the opportunity to benchmark the selected tool combinations based on the excellent report generated by the pipeline. This HTML report aggregates the output of several tools for quality evaluation of the assemblies (e.g. BUSCO [2] or QUAST [3]) generated by the different assemblers, in addition to the running time and configuration parameters. Such information is of great help to identify the best-suited pipeline, as exemplified by the authors using four datasets of different taxonomic origins. Finally, CulebrONT can handle multiple samples in parallel, which makes it a good solution for laboratories looking for multiple assemblies on a large scale. References 1. Orjuela J, Comte A, Ravel S, Charriat F, Vi T, Sabot F, Cunnac S (2022) CulebrONT: a streamlined long reads multi-assembler pipeline for prokaryotic and eukaryotic genomes. bioRxiv, 2021.07.19.452922, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.19.452922 2. Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM (2015) BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics, 31, 3210–3212. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351 3. Gurevich A, Saveliev V, Vyahhi N, Tesler G (2013) QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics, 29, 1072–1075. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086 | CulebrONT: a streamlined long reads multi-assembler pipeline for prokaryotic and eukaryotic genomes | Julie Orjuela, Aurore Comte, Sébastien Ravel, Florian Charriat, Tram Vi, Francois Sabot, Sébastien Cunnac | <p style="text-align: justify;">Using long reads provides higher contiguity and better genome assemblies. However, producing such high quality sequences from raw reads requires to chain a growing set of tools, and determining the best workflow is ... |  | Bioinformatics | Raúl Castanera | Valentine Murigneux | 2022-02-22 16:21:25 | View |