Latest recommendations

| Id | Title▲ | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

08 Apr 2022

POSTPRINT

Phylogenetics in the Genomic EraCéline Scornavacca, Frédéric Delsuc, Nicolas Galtier https://hal.inria.fr/PGE/“Phylogenetics in the Genomic Era” brings together experts in the field to present a comprehensive synthesisRecommended by Robert Waterhouse and Karen MeusemannE-book: Phylogenetics in the Genomic Era (Scornavacca et al. 2021) This book was not peer-reviewed by PCI Genomics. It has undergone an internal review by the editors. Accurate reconstructions of the relationships amongst species and the genes encoded in their genomes are an essential foundation for almost all evolutionary inferences emerging from downstream analyses. Molecular phylogenetics has developed as a field over many decades to build suites of models and methods to reconstruct reliable trees that explain, support, or refute such inferences. The genomic era has brought new challenges and opportunities to the field, opening up new areas of research and algorithm development to take advantage of the accumulating large-scale data. Such ‘big-data’ phylogenetics has come to be known as phylogenomics, which broadly aims to connect molecular and evolutionary biology research to address questions centred on relationships amongst taxa, mechanisms of molecular evolution, and the biological functions of genes and other genomic elements. This book brings together experts in the field to present a comprehensive synthesis of Phylogenetics in the Genomic Era, covering key conceptual and methodological aspects of how to build accurate phylogenies and how to apply them in molecular and evolutionary research. The paragraphs below briefly summarise the five constituent parts of the book, highlighting the key concepts, methods, and applications that each part addresses. Being organised in an accessible style, while presenting details to provide depth where necessary, and including guides describing real-world examples of major phylogenomic tools, this collection represents an invaluable resource, particularly for students and newcomers to the field of phylogenomics. Part 1: Phylogenetic analyses in the genomic era Modelling how sequences evolve is a fundamental cornerstone of phylogenetic reconstructions. This part of the book introduces the reader to phylogenetic inference methods and algorithmic optimisations in the contexts of Markov, Maximum Likelihood, and Bayesian models of sequence evolution. The main concepts and theoretical considerations are mapped out for probabilistic Markov models, efficient tree building with Maximum Likelihood methods, and the flexibility and robustness of Bayesian approaches. These are supported with practical examples of phylogenomic applications using the popular tools RAxML and PhyloBayes. By considering theoretical, algorithmic, and practical aspects, these chapters provide readers with a holistic overview of the challenges and recent advances in developing scalable phylogenetic analyses in the genomic era. Part 2: Data quality, model adequacy This part focuses on the importance of considering the appropriateness of the evolutionary models used and the accuracy of the underlying molecular and genomic data. Both these aspects can profoundly affect the results when applying current phylogenomic methods to make inferences about complex biological and evolutionary processes. A clear example is presented for methods for building multiple sequence alignments and subsequent filtering approaches that can greatly impact phylogeny inference. The importance of error detection in (meta)barcode sequencing data is also highlighted, with solutions offered by the MACSE_BARCODE pipeline for accurate taxonomic assignments. Orthology datasets are essential markers for phylogenomic inferences, but the overview of concepts and methods presented shows that they too face challenges with respect to model selection and data quality. Finally, an innovative approach using ancestral gene order reconstructions provides new perspectives on how to assess gene tree accuracy for phylogenomic analyses. By emphasising through examples the importance of using appropriate evolutionary models and assessing input data quality, these chapters alert readers to key limitations that the field as a whole strives to address. Part 3: Resolving phylogenomic conflicts Conflicting phylogenetic signals are commonplace and may derive from statistical or systematic bias. This part of the book addresses possible causes of conflict, discordance between gene trees and species trees and how processes that lead to such conflicts can be described by phylogenetic models. Furthermore, it provides an overview of various models and methods with examples in phylogenomics including their pros and cons. Outlined in detail is the multispecies coalescent model (MSC) and its applications in phylogenomics. An interesting aspect is that different phylogenetic signals leading to conflict are in fact a key source of information rather than a problem that can – and should – be used to point to events like introgression or hybridisation, highlighting possible future trends in this research area. Last but not least, this part of the book also addresses inferring species trees by concatenating single multiple sequence alignments (gene alignments) versus inferring the species tree based on ensembles of single gene trees pointing out advantages and disadvantages of both approaches. As an important take home message from these chapters, it is recommended to be flexible and identify the most appropriate approach for each dataset to be analysed since this may tremendously differ depending on the dataset, setting, taxa, and phylogenetic level addressed by the researcher. Part 4: Functional evolutionary genomics In this part of the book the focus shifts to functional considerations of phylogenomics approaches both in terms of molecular evolution and adaptation and with respect to gene expression. The utility of multi-species analysis is clearly presented in the context of annotating functional genomic elements through quantifying evolutionary constraint and protein-coding potential. An historical perspective on characterising rates of change highlights how phylogenomic datasets help to understand the modes of molecular evolution across the genome, over time, and between lineages. These are contextualised with respect to the specific aim of detecting signatures of adaptation from protein-coding DNA alignments using the example of the MutSelDP-ω∗ model. This is extended with the presentation of the generally rare case of adaptive sequence convergence, where consideration of appropriate models and knowledge of gene functions and phenotypic effects are needed. Constrained or relaxed, selection pressures on sequence or copy-number affect genomic elements in different ways, making the very concept of function difficult to pin down despite it being fundamental to relate the genome to the phenotype and organismal fitness. Here gene expression provides a measurable intermediate, for which the Expression Comparison tool from the Bgee suite allows exploration of expression patterns across multiple animal species taking into account anatomical homology. Overall, phylogenomics applications in functional evolutionary genomics build on a rich theoretical history from molecular analyses where integration with knowledge of gene functions is challenging but critical. Part 5: Phylogenomic applications Rather than attempting to review the full extent of applications linked to phylogenomics, this part of the book focuses on providing detailed specific insights into selected examples and methods concerning i) estimating divergence times, and ii) species delimitation in the era of ‘omics’ data. With respect to estimating divergence times, an exemplary overview is provided for fossil data recovered from geological records, either using fossil data as calibration points with an extant-species-inferred phylogeny, or using a fossilised birth-death process as a mechanistic model that accounts for lineage diversification. Included is a tutorial for a joint approach to infer phylogenies and estimate divergence times using the RevBayes software with various models implemented for different applications and datasets incorporating molecular and morphological data. An interesting excursion is outlined focusing on timescale estimates with respect to viral evolution introducing BEAGLE, a high-performance likelihood-calculation platform that can be used on multi-core systems. As a second major subject, species delimitation is addressed since currently the increasing amount of available genomic data enables extensive inferences, for instance about the degree of genetic isolation among species and ancient and recent introgression events. Describing the history of molecular species delimitation up to the current genomic era and presenting widely used computational methods incorporating single- and multi-locus genomic data, pros and cons are addressed. Finally, a proposal for a new method for delimiting species based on empirical criteria is outlined. In the closing chapter of this part of the book, BPP (Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo program) for analysing multi-locus sequence data under the multispecies coalescent (MSC) model with and without introgression is introduced, including a tutorial. These examples together provide accessible details on key conceptual and methodological aspects related to the application of phylogenetics in the genomic era. References Scornavacca C, Delsuc F, Galtier N (2021) Phylogenetics in the Genomic Era. https://hal.inria.fr/PGE/ | Phylogenetics in the Genomic Era | Céline Scornavacca, Frédéric Delsuc, Nicolas Galtier | <p style="text-align: justify;">Molecular phylogenetics was born in the middle of the 20th century, when the advent of protein and DNA sequencing offered a novel way to study the evolutionary relationships between living organisms. The first 50 ye... |  | Bacteria and archaea, Bioinformatics, Evolutionary genomics, Functional genomics, Fungi, Plants, Population genomics, Vertebrates, Viruses and transposable elements | Robert Waterhouse | 2022-03-15 17:43:52 | View | |

07 Feb 2023

RAREFAN: A webservice to identify REPINs and RAYTs in bacterial genomesFrederic Bertels, Julia von Irmer, Carsten Fortmann-Grote https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.22.493013A workflow for studying enigmatic non-autonomous transposable elements across bacteriaRecommended by Gavin Douglas based on reviews by Sophie Abby and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Sophie Abby and 1 anonymous reviewer

Repetitive extragenic palindromic sequences (REPs) are common repetitive elements in bacterial genomes (Gilson et al., 1984; Stern et al., 1984). In 2011, Bertels and Rainey identified that REPs are overrepresented in pairs of inverted repeats, which likely form hairpin structures, that they referred to as “REP doublets forming hairpins” (REPINs). Based on bioinformatics analyses, they argued that REPINs are likely selfish elements that evolved from REPs flanking particular transposes (Bertels and Rainey, 2011). These transposases, so-called REP-associated tyrosine transposases (RAYTs), were known to be highly associated with the REP content in a genome and to have characteristic upstream and downstream flanking REPs (Nunvar et al., 2010). The flanking REPs likely enable RAYT transposition, and their horizontal replication is physically linked to this process. In contrast, Bertels and Rainey hypothesized that REPINs are selfish elements that are highly replicated due to the similarity in arrangement to these RAYT-flanking REPs, but independent of RAYT transposition and generally with no impact on bacterial fitness (Bertels and Rainey, 2011). This last point was especially contentious, as REPINs are highly conserved within species (Bertels and Rainey, 2023), which is unusual for non-beneficial bacterial DNA (Mira et al., 2001). Bertels and Rainey have since refined their argument to be that REPINs must provide benefits to host cells, but that there are nonetheless signatures of intragenomic conflict in genomes associated with these elements (Bertels and Rainey, 2023). These signatures reflect the divergent levels of selections driving REPIN distribution: selection at the level of each DNA element and selection on each individual bacterium. I found this observation particularly interesting as I and my colleague recently argued that these divergent levels of selection, and the interaction between them, is key to understanding bacterial pangenome diversity (Douglas and Shapiro, 2021). REPINs could be an excellent system for investigating these levels of selection across bacteria more generally. The problem is that REPINs have not been widely characterized in bacterial genomes, partially because no bioinformatic workflow has been available for this purpose. To address this problem, Fortmann-Grote et al. (2023) developed RAREFAN, which is a web server for identifying RAYTs and associated REPINs in a set of input genomes. The authors showcase their tool by applying it to 49 Stenotrophomonas maltophilia genomes and providing examples of how to identify and assess RAYT-REPIN hits. The workflow requires several manual steps, but nonetheless represents a straightforward and standardized approach. Overall, this workflow should enable RAYTs and REPINs to be identified across diverse bacterial species, which will facilitate further investigation into the mechanisms driving their maintenance and spread. References Bertels F, Rainey PB (2023) Ancient Darwinian replicators nested within eubacterial genomes. BioEssays, 45, 2200085. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.202200085 Bertels F, Rainey PB (2011) Within-Genome Evolution of REPINs: a New Family of Miniature Mobile DNA in Bacteria. PLOS Genetics, 7, e1002132. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002132 Douglas GM, Shapiro BJ (2021) Genic Selection Within Prokaryotic Pangenomes. Genome Biology and Evolution, 13, evab234. https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evab234 Fortmann-Grote C, Irmer J von, Bertels F (2023) RAREFAN: A webservice to identify REPINs and RAYTs in bacterial genomes. bioRxiv, 2022.05.22.493013, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.22.493013 Gilson E, Clément J m., Brutlag D, Hofnung M (1984) A family of dispersed repetitive extragenic palindromic DNA sequences in E. coli. The EMBO Journal, 3, 1417–1421. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb01986.x Mira A, Ochman H, Moran NA (2001) Deletional bias and the evolution of bacterial genomes. Trends in Genetics, 17, 589–596. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9525(01)02447-7 Nunvar J, Huckova T, Licha I (2010) Identification and characterization of repetitive extragenic palindromes (REP)-associated tyrosine transposases: implications for REP evolution and dynamics in bacterial genomes. BMC Genomics, 11, 44. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-11-44 Stern MJ, Ames GF-L, Smith NH, Clare Robinson E, Higgins CF (1984) Repetitive extragenic palindromic sequences: A major component of the bacterial genome. Cell, 37, 1015–1026. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(84)90436-7 | RAREFAN: A webservice to identify REPINs and RAYTs in bacterial genomes | Frederic Bertels, Julia von Irmer, Carsten Fortmann-Grote | <p style="text-align: justify;">Compared to eukaryotes, repetitive sequences are rare in bacterial genomes and usually do not persist for long. Yet, there is at least one class of persistent prokaryotic mobile genetic elements: REPINs. REPINs are ... | Bacteria and archaea, Bioinformatics, Evolutionary genomics, Viruses and transposable elements | Gavin Douglas | 2022-06-07 08:21:34 | View | ||

02 Apr 2021

Semi-artificial datasets as a resource for validation of bioinformatics pipelines for plant virus detectionLucie Tamisier, Annelies Haegeman, Yoika Foucart, Nicolas Fouillien, Maher Al Rwahnih, Nihal Buzkan, Thierry Candresse, Michela Chiumenti, Kris De Jonghe, Marie Lefebvre, Paolo Margaria, Jean Sébastien Reynard, Kristian Stevens, Denis Kutnjak, Sébastien Massart https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4584718Toward a critical assessment of virus detection in plantsRecommended by Hadi Quesneville based on reviews by Alexander Suh and 1 anonymous reviewerThe advent of High Throughput Sequencing (HTS) since the last decade has revealed previously unsuspected diversity of viruses as well as their (sometimes) unexpected presence in some healthy individuals. These results demonstrate that genomics offers a powerful tool for studying viruses at the individual level, allowing an in-depth inventory of those that are infecting an organism. Such approaches make it possible to study viromes with an unprecedented level of detail, both qualitative and quantitative, which opens new venues for analyses of viruses of humans, animals and plants. Consequently, the diagnostic field is using more and more HTS, fueling the need for efficient and reliable bioinformatics tools. Many such tools have already been developed, but in plant disease diagnostics, validation of the bioinformatics pipelines used for the detection of viruses in HTS datasets is still in its infancy. There is an urgent need for benchmarking the different tools and algorithms using well-designed reference datasets generated for this purpose. This is a crucial step to move forward and to improve existing solutions toward well-standardized bioinformatics protocols. This context has led to the creation of the Plant Health Bioinformatics Network (PHBN), a Euphresco network project aiming to build a bioinformatics community working on plant health. One of their objectives is to provide researchers with open-access reference datasets allowing to compare and validate virus detection pipelines. In this framework, Tamisier et al. [1] present real, semi-artificial, and completely artificial datasets, each aimed at addressing challenges that could affect virus detection. These datasets comprise real RNA-seq reads from virus-infected plants as well as simulated virus reads. Such a work, providing open-access datasets for benchmarking bioinformatics tools, should be encouraged as they are key to software improvement as demonstrated by the well-known success story of the protein structure prediction community: their pioneer community-wide effort, called Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP)[2], has been providing research groups since 1994 with an invaluable way to objectively test their structure prediction methods, thereby delivering an independent assessment of state-of-art protein-structure modelling tools. Following this success, many other bioinformatic community developed similar “competitions”, such as RNA-puzzles [3] to predict RNA structures, Critical Assessment of Function Annotation [4] to predict gene functions, Critical Assessment of Prediction of Interactions [5] to predict protein-protein interactions, Assemblathon [6] for genome assembly, etc. These are just a few examples from a long list of successful initiatives. Such efforts enable rigorous assessments of tools, stimulate the developers’ creativity, but also provide user communities with a state-of-art evaluation of available tools. Inspired by these success stories, the authors propose a “VIROMOCK challenge” [7], asking researchers in the field to test their tools and to provide feedback on each dataset through a repository. This initiative, if well followed, will undoubtedly improve the field of virus detection in plants, but also probably in many other organisms. This will be a major contribution to the field of viruses, leading to better diagnostics and, consequently, a better understanding of viral diseases, thus participating in promoting human, animal and plant health. References [1] Tamisier, L., Haegeman, A., Foucart, Y., Fouillien, N., Al Rwahnih, M., Buzkan, N., Candresse, T., Chiumenti, M., De Jonghe, K., Lefebvre, M., Margaria, P., Reynard, J.-S., Stevens, K., Kutnjak, D. and Massart, S. (2021) Semi-artificial datasets as a resource for validation of bioinformatics pipelines for plant virus detection. Zenodo, 4273791, version 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Genomics. doi: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4273791 [2] Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction” (CASP) - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CASP [3] RNA-puzzles - https://www.rnapuzzles.org [4] Critical Assessment of Function Annotation (CAFA) - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Critical_Assessment_of_Function_Annotation [5] Critical Assessment of Prediction of Interactions (CAPI) - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Critical_Assessment_of_Prediction_of_Interactions [6] Assemblathon - https://assemblathon.org [7] VIROMOCK challenge - https://gitlab.com/ilvo/VIROMOCKchallenge | Semi-artificial datasets as a resource for validation of bioinformatics pipelines for plant virus detection | Lucie Tamisier, Annelies Haegeman, Yoika Foucart, Nicolas Fouillien, Maher Al Rwahnih, Nihal Buzkan, Thierry Candresse, Michela Chiumenti, Kris De Jonghe, Marie Lefebvre, Paolo Margaria, Jean Sébastien Reynard, Kristian Stevens, Denis Kutnjak, Séb... | <p>The widespread use of High-Throughput Sequencing (HTS) for detection of plant viruses and sequencing of plant virus genomes has led to the generation of large amounts of data and of bioinformatics challenges to process them. Many bioinformatics... |  | Bioinformatics, Plants, Viruses and transposable elements | Hadi Quesneville | 2020-11-27 14:31:47 | View | |

10 Jul 2023

SNP discovery by exome capture and resequencing in a pea genetic resource collectionG. Aubert, J. Kreplak, M. Leveugle, H. Duborjal, A. Klein, K. Boucherot, E. Vieille, M. Chabert-Martinello, C. Cruaud, V. Bourion, I. Lejeune-Hénaut, M.L. Pilet-Nayel, Y. Bouchenak-Khelladi, N. Francillonne, N. Tayeh, J.P. Pichon, N. Rivière, J. Burstin https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.03.502586The value of a large Pisum SNP datasetRecommended by Wanapinun Nawae based on reviews by Rui Borges and 1 anonymous reviewerOne important goal of modern genetics is to establish functional associations between genotype and phenotype. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are numerous and widely distributed in the genome and can be obtained from nucleic acid sequencing (1). SNPs allow for the investigation of genetic diversity, which is critical for increasing crop resilience to the challenges posed by global climate change. The associations between SNPs and phenotypes can be captured in genome-wide association studies. SNPs can also be used in combination with machine learning, which is becoming more popular for predicting complex phenotypic traits like yield and biotic and abiotic stress tolerance from genotypic data (2). The availability of many SNP datasets is important in machine learning predictions because this approach requires big data to build a comprehensive model of the association between genotype and phenotype. Aubert and colleagues have studied, as part of the PeaMUST project, the genetic diversity of 240 Pisum accessions (3). They sequenced exome-enriched genomic libraries, a technique that enables the identification of high-density, high-quality SNPs at a low cost (4). This technique involves capturing and sequencing only the exonic regions of the genome, which are the protein-coding regions. A total of 2,285,342 SNPs were obtained in this study. The analysis of these SNPs with the annotations of the genome sequence of one of the studied pea accessions (5) identified a number of SNPs that could have an impact on gene activity. Additional analyses revealed 647,220 SNPs that were unique to individual pea accessions, which might contribute to the fitness and diversity of accessions in different habitats. Phylogenetic and clustering analyses demonstrated that the SNPs could distinguish Pisum germplasms based on their agronomic and evolutionary histories. These results point out the power of selected SNPs as markers for identifying Pisum individuals. Overall, this study found high-quality SNPs that are meaningful in a biological context. This dataset was derived from a large set of germplasm and is thus particularly useful for studying genotype-phenotype associations, as well as the diversity within Pisum species. These SNPs could also be used in breeding programs to develop new pea varieties that are resilient to abiotic and biotic stressors. References

https://doi.org/10.1139/gen-2021-005

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-022-03559-z

https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.03.502586

https://doi.org/10.1534/g3.115.018564

| SNP discovery by exome capture and resequencing in a pea genetic resource collection | G. Aubert, J. Kreplak, M. Leveugle, H. Duborjal, A. Klein, K. Boucherot, E. Vieille, M. Chabert-Martinello, C. Cruaud, V. Bourion, I. Lejeune-Hénaut, M.L. Pilet-Nayel, Y. Bouchenak-Khelladi, N. Francillonne, N. Tayeh, J.P. Pichon, N. Rivière, J. B... | <p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>Background & Summary</strong></p> <p style="text-align: justify;">In addition to being the model plant used by Mendel to establish genetic laws, pea (<em>Pisum sativum</em> L., 2n=14) is a major pulse c... |  | Plants, Population genomics | Wanapinun Nawae | 2022-11-29 09:29:06 | View | |

08 Nov 2022

Somatic mutation detection: a critical evaluation through simulations and reanalyses in oaksSylvain Schmitt, Thibault Leroy, Myriam Heuertz, Niklas Tysklind https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.11.462798How to best call the somatic mosaic tree?Recommended by Nicolas Bierne based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersAny multicellular organism is a molecular mosaic with some somatic mutations accumulated between cell lineages. Big long-lived trees have nourished this imaginary of a somatic mosaic tree, from the observation of spectacular phenotypic mosaics and also because somatic mutations are expected to potentially be passed on to gametes in plants (review in Schoen and Schultz 2019). The lower cost of genome sequencing now offers the opportunity to tackle the issue and identify somatic mutations in trees. However, when it comes to characterizing this somatic mosaic from genome sequences, things become much more difficult than one would think in the first place. What separates cell lineages ontogenetically, in cell division number, or in time? How to sample clonal cell populations? How do somatic mutations distribute in a population of cells in an organ or an organ sample? Should they be fixed heterozygotes in the sample of cells sequenced or be polymorphic? Do we indeed expect somatic mutations to be fixed? How should we identify and count somatic mutations? To date, the detection of somatic mutations has mostly been done with a single variant caller in a given study, and we have little perspective on how different callers provide similar or different results. Some studies have used standard SNP callers that assumed a somatic mutation is fixed at the heterozygous state in the sample of cells, with an expected allele coverage ratio of 0.5, and less have used cancer callers, designed to detect mutations in a fraction of the cells in the sample. However, standard SNP callers detect mutations that deviate from a balanced allelic coverage, and different cancer callers can have different characteristics that should affect their outcomes. In order to tackle these issues, Schmitt et al. (2022) conducted an extensive simulation analysis to compare different variant callers. Then, they reanalyzed two large published datasets on pedunculate oak, Quercus robur. The analysis of in silico somatic mutations allowed the authors to evaluate the performance of different variant callers as a function of the allelic fraction of somatic mutations and the sequencing depth. They found one of the seven callers to provide better and more robust calls for a broad set of allelic fractions and sequencing depths. The reanalysis of published datasets in oaks with the most effective cancer caller of the in silico analysis allowed them to identify numerous low-frequency mutations that were missed in the original studies. I recommend the study of Schmitt et al. (2022) first because it shows the benefit of using cancer callers in the study of somatic mutations, whatever the allelic fraction you are interested in at the end. You can select fixed heterozygotes if this is your ultimate target, but cancer callers allow you to have in addition a valuable overview of the allelic fractions of somatic mutations in your sample, and most do as well as SNP callers for fixed heterozygous mutations. In addition, Schmitt et al. (2022) provide the pipelines that allow investigating in silico data that should correspond to a given study design, encouraging to compare different variant callers rather than arbitrarily going with only one. We can anticipate that the study of somatic mutations in non-model species will increasingly attract attention now that multiple tissues of the same individual can be sequenced at low cost, and the study of Schmitt et al. (2022) paves the way for questioning and choosing the best variant caller for the question one wants to address. References Schoen DJ, Schultz ST (2019) Somatic Mutation and Evolution in Plants. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 50, 49–73. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110218-024955 Schmitt S, Leroy T, Heuertz M, Tysklind N (2022) Somatic mutation detection: a critical evaluation through simulations and reanalyses in oaks. bioRxiv, 2021.10.11.462798. ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.11.462798 | Somatic mutation detection: a critical evaluation through simulations and reanalyses in oaks | Sylvain Schmitt, Thibault Leroy, Myriam Heuertz, Niklas Tysklind | <p style="text-align: justify;">1. Mutation, the source of genetic diversity, is the raw material of evolution; however, the mutation process remains understudied, especially in plants. Using both a simulation and reanalysis framework, we set out ... |  | Bioinformatics, Plants | Nicolas Bierne | Anonymous, Anonymous | 2022-04-28 13:24:19 | View |

07 Sep 2023

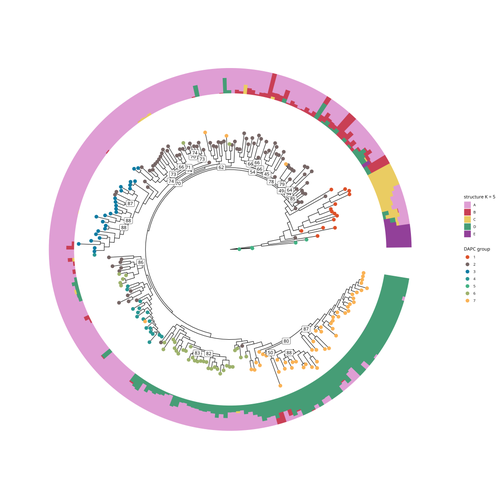

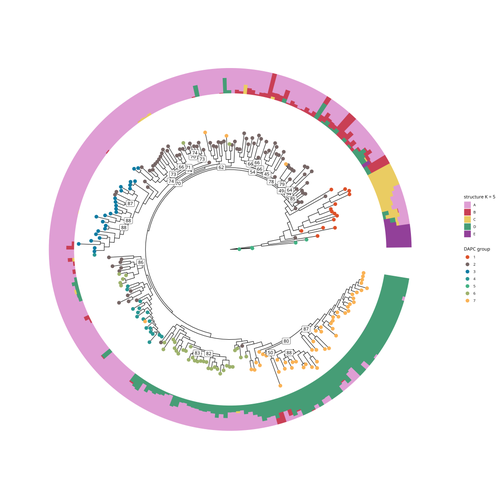

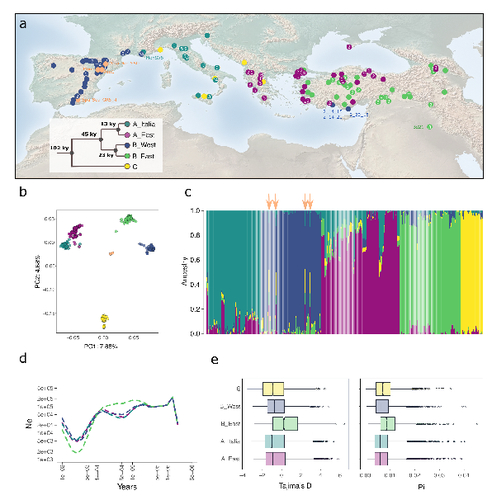

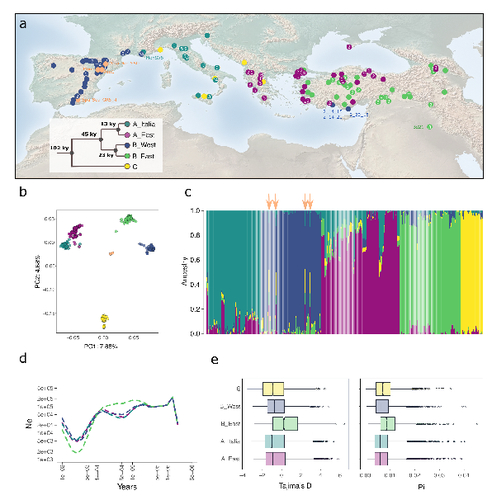

The demographic history of the wild crop relative Brachypodium distachyon is shaped by distinct past and present ecological nichesNikolaos Minadakis, Hefin Williams, Robert Horvath, Danka Caković, Christoph Stritt, Michael Thieme, Yann Bourgeois, Anne C. Roulin https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.01.543285Natural variation and adaptation in Brachypodium distachyonRecommended by Josep Casacuberta based on reviews by Thibault Leroy and 1 anonymous reviewerIdentifying the genetic factors that allow plant adaptation is a major scientific question that is particularly relevant in the face of the climate change that we are already experiencing. To address this, it is essential to have genetic information on a high number of accessions (i.e., plants registered with unique accession numbers) growing under contrasting environmental conditions. There is already an important number of studies addressing these issues in the plant Arabidopsis thaliana, but there is a need to expand these analyses to species that play key roles in wild ecosystems and are close to very relevant crops, as is the case of grasses. The work of Minadakis, Roulin and co-workers (1) presents a Brachypodium distachyon panel of 332 fully sequences accessions that covers the whole species distribution across a wide range of bioclimatic conditions, which will be an invaluable tool to fill this gap. In addition, the authors use this data to start analyzing the population structure and demographic history of this plant, suggesting that the species experienced a shift of its distribution following the Last Glacial Maximum, which may have forced the species into new habitats. The authors also present a modeling of the niches occupied by B. distachyon together with an analysis of the genetic clades found in each of them, and start analyzing the different adaptive loci that may have allowed the species’ expansion into different bioclimatic areas. In addition to the importance of the resources made available by the authors for the scientific community, the analyses presented are well done and carefully discussed, and they highlight the potential of these new resources to investigate the genetic bases of plant adaptation. References 1. Nikolaos Minadakis, Hefin Williams, Robert Horvath, Danka Caković, Christoph Stritt, Michael Thieme, Yann Bourgeois, Anne C. Roulin. The demographic history of the wild crop relative Brachypodium distachyon is shaped by distinct past and present ecological niches. bioRxiv, 2023.06.01.543285, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.01.543285 | The demographic history of the wild crop relative *Brachypodium distachyon* is shaped by distinct past and present ecological niches | Nikolaos Minadakis, Hefin Williams, Robert Horvath, Danka Caković, Christoph Stritt, Michael Thieme, Yann Bourgeois, Anne C. Roulin | <p style="text-align: justify;">Closely related to economically important crops, the grass <em>Brachypodium distachyon</em> has been originally established as a pivotal species for grass genomics but more recently flourished as a model for develop... |  | Evolutionary genomics, Functional genomics, Plants, Population genomics | Josep Casacuberta | 2023-06-14 15:28:30 | View | |

15 Jan 2024

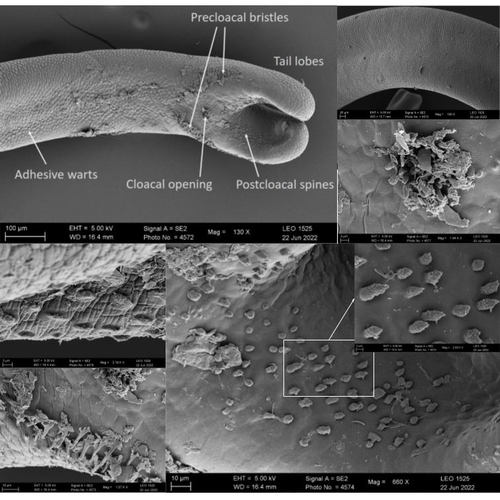

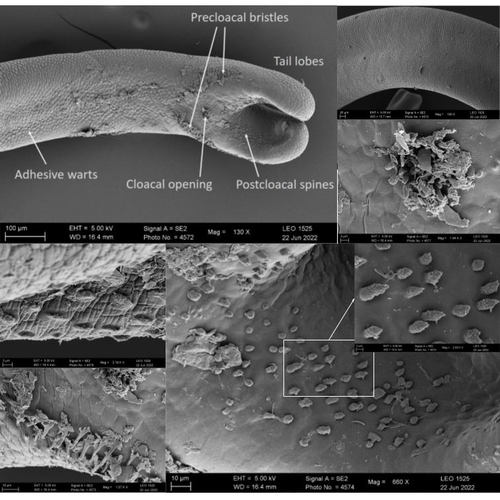

The genome sequence of the Montseny horsehair worm, Gordionus montsenyensis sp. nov., a key resource to investigate Ecdysozoa evolutionEleftheriadi Klara, Guiglielmoni Nadège, Salces-Ortiz Judit, Vargas-Chávez Carlos, Martínez-Redondo Gemma I, Gut Marta, Flot Jean François, Schmidt-Rhaesa Andreas, Fernández Rosa https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.26.546503Embarking on a novel journey in Metazoa evolution through the pioneering sequencing of a key underrepresented lineageRecommended by Juan C. Opazo based on reviews by Gonzalo Riadi and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Gonzalo Riadi and 2 anonymous reviewers

Whole genome sequences are revolutionizing our understanding across various biological fields. They not only shed light on the evolution of genetic material but also uncover the genetic basis of phenotypic diversity. The sequencing of underrepresented lineages, such as the one presented in this study, is of critical importance. It is crucial in filling significant gaps in our understanding of Metazoa evolution. Despite the wealth of genome sequences in public databases, it is crucial to acknowledge that some lineages across the Tree of Life are underrepresented or absent. This research represents a significant step towards addressing this imbalance, contributing to the collective knowledge of the global scientific community. In this genome note, as part of the European Reference Genome Atlas pilot effort to generate reference genomes for European biodiversity (Mc Cartney et al. 2023), Klara Eleftheriadi and colleagues (Eleftheriadi et al. 2023) make a significant effort to add a genome sequence of an unrepresented group in the animal Tree of Life. More specifically, they present a taxonomic description and chromosome-level genome assembly of a newly described species of horsehair worm (Gordionus montsenyensis). Their sequence methodology gave rise to an assembly of 396 scaffolds totaling 288 Mb, with an N50 value of 64.4 Mb, where 97% of this assembly is grouped into five pseudochromosomes. The nuclear genome annotation predicted 10,320 protein-coding genes, and they also assembled the circular mitochondrial genome into a 15-kilobase sequence. The selection of a species representing the phylum Nematomorpha, a group of parasitic organisms belonging to the Ecdysozoa lineage, is good, since today, there is only one publicly available genome for this animal phylum (Cunha et al. 2023). Interestingly, this article shows, among other things, that the species analyzed has lost ∼30% of the universal Metazoan genes. Efforts, like the one performed by Eleftheriadi and colleagues, are necessary to gain more insights, for example, on the evolution of this massive gene lost in this group of animals.

Cunha, T. J., de Medeiros, B. A. S, Lord, A., Sørensen, M. V., and Giribet, G. (2023). Rampant Loss of Universal Metazoan Genes Revealed by a Chromosome-Level Genome Assembly of the Parasitic Nematomorpha. Current Biology, 33 (16): 3514–21.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2023.07.003 Eleftheriadi, K., Guiglielmoni, N., Salces-Ortiz, J., Vargas-Chavez, C., Martínez-Redondo, G. I., Gut, M., Flot, J.-F., Schmidt-Rhaesa, A., and Fernández, R. (2023). The Genome Sequence of the Montseny Horsehair worm, Gordionus montsenyensis sp. Nov., a Key Resource to Investigate Ecdysozoa Evolution. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.26.546503 Mc Cartney, A. M., Formenti, G., Mouton, A., De Panis, D., Marins, L. S., Leitão, H. G., Diedericks, G., et al. (2023). The European Reference Genome Atlas: Piloting a Decentralised Approach to Equitable Biodiversity Genomics. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.09.25.559365 | The genome sequence of the Montseny horsehair worm, *Gordionus montsenyensis* sp. nov., a key resource to investigate Ecdysozoa evolution | Eleftheriadi Klara, Guiglielmoni Nadège, Salces-Ortiz Judit, Vargas-Chávez Carlos, Martínez-Redondo Gemma I, Gut Marta, Flot Jean François, Schmidt-Rhaesa Andreas, Fernández Rosa | <p>Nematomorpha, also known as Gordiacea or Gordian worms, are a phylum of parasitic organisms that belong to the Ecdysozoa, a clade of invertebrate animals characterized by molting. They are one of the less scientifically studied animal phyla, an... |  | ERGA Pilot | Juan C. Opazo | 2023-06-29 10:31:36 | View | |

06 Feb 2024

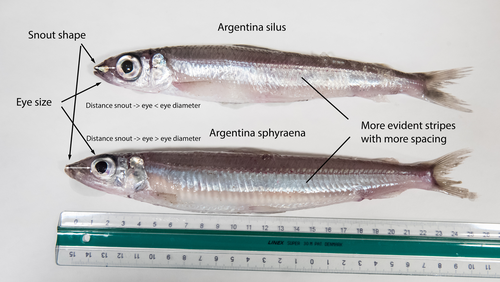

The need of decoding life for taking care of biodiversity and the sustainable use of nature in the Anthropocene - a Faroese perspectiveSvein-Ole Mikalsen, Jari í Hjøllum, Ian Salter, Anni Djurhuus, Sunnvør í Kongsstovu https://doi.org/10.32942/X21S4CWhy sequence everything? A raison d’être for the Genome Atlas of Faroese EcologyRecommended by Stephen Richards based on reviews by Tereza Manousaki and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Tereza Manousaki and 1 anonymous reviewer

When discussing the Earth BioGenome Project with scientists and potential funding agencies, one common question is: why sequence everything? Whether sequencing a subset would be more optimal is not an unreasonable question given what we know about the mathematics of importance and Pareto’s 80:20 principle, that 80% of the benefits can come from 20% of the effort. However, one must remember that this principle is an observation made in hindsight and selecting the most effective 20% of experiments is difficult. As an example, few saw great applied value in comparative genomic analysis of the archaea Haloferax mediterranei, but this enabled the discovery of CRISPR/Cas9 technology (1). When discussing whether or not to sequence all life on our planet, smaller countries such as the Faroe Islands are seldom mentioned.

1 Mojica, F. J., Díez-Villaseñor, C. S., García-Martínez, J. & Soria, E. Intervening sequences of regularly spaced prokaryotic repeats derive from foreign genetic elements. J Mol Evol 60, 174-182 (2005). 2 Mikalsen, S-O., Hjøllum, J. í., Salter, I., Djurhuus, A. & Kongsstovu, S. í. The need of decoding life for taking care of biodiversity and the sustainable use of nature in the Anthropocene – a Faroese perspective. EcoEvoRxiv (2024), ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.32942/X21S4C | The need of decoding life for taking care of biodiversity and the sustainable use of nature in the Anthropocene - a Faroese perspective | Svein-Ole Mikalsen, Jari í Hjøllum, Ian Salter, Anni Djurhuus, Sunnvør í Kongsstovu | <p>Biodiversity is under pressure, mainly due to human activities and climate change. At the international policy level, it is now recognised that genetic diversity is an important part of biodiversity. The availability of high-quality reference g... |  | ERGA, ERGA Pilot, Population genomics, Vertebrates | Stephen Richards | 2023-07-31 16:59:33 | View | |

22 Nov 2023

The slow evolving genome of the xenacoelomorph worm Xenoturbella bockiPhilipp H. Schiffer, Paschalis Natsidis, Daniel J. Leite, Helen Robertson, François Lapraz, Ferdinand Marlétaz, Bastian Fromm, Liam Baudry, Fraser Simpson, Eirik Høye, Anne-C. Zakrzewski, Paschalia Kapli, Katharina J. Hoff, Steven Mueller, Martial Marbouty, Heather Marlow, Richard R. Copley, Romain Koszul, Peter Sarkies, Maximilian J. Telford https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.24.497508Genomic idiosyncrasies of Xenoturbella bocki: morphologically simple yet genetically complexRecommended by Rosa Fernández based on reviews by Christopher Laumer and 1 anonymous reviewerXenoturbella is a genus of morphologically simple bilaterians inhabiting benthic environments. Until very recently, only one species was known from the genus, Xenoturbella bocki Westblad 1949 [1]. Less than a decade ago, five more species were discovered (X. churro, X. monstrosa, X. profunda, X. hollandorum [2] and X. japonica [3]). These enigmatic animals lack an anus, a coelom, reproductive organs, nephrocytes and a centralized nervous system [1]. The systematic classification of the genus has substantially changed in the last decades, with first being considered as its own phylum (Xenoturbellida) and then being clustered together with acoels and nemertodermatids into the phylum Xenacoelomorpha [4,5]. The phylogenetic position of the xenacoelomorphs has been recalcitrant to resolution, with its position ranging from being the sister group to Nephrozoa (ie, protostomes and deuterostomes [6]) to the sister group to Ambulacraria (ie, Hemichordata and Echinodermata) in a clade called Xenambulacraria [4]. Recent studies based on expanded datasets and more refined analyses support either topology [7,8]. Either way, it is clear that additional studies on Xenoturbella could provide important insights into the origins of bilaterian traits such as the anus, the nephrons and the evolution of a centralized nervous system.

In any case, we are approaching a qualitative jump in how we understand phylogenomics thanks to efforts derived from the availability of chromosome-level genome assemblies for a growing number of species. Exciting times are ahead for us, evolutionary biologists, to explore what high-quality genomes - in combination with multiomics datasets - will reveal about animal evolution. I am personally really looking forward to it. References 1. Westblad E. (1949). Xenoturbella bocki n.g., n.sp., a peculiar, primitive Turbellarian type. Arkiv för Zoologi 1, 3-29 (1949). 2. Rouse, G. W., Wilson, N. G., Carvajal, J. I. & Vrijenhoek, R. C. New deep-sea species of Xenoturbella and the position of Xenacoelomorpha. Nature 530, 94–97 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16545 3. Nakano, H. et al. Correction to: A new species of Xenoturbella from the western Pacific Ocean and the evolution of Xenoturbella. BMC Evol. Biol. 18, 1–2 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-018-1190-5https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-018-1190-5 4. Philippe, H. et al. Acoelomorph flatworms are deuterostomes related to Xenoturbella. Nature 470, 255–258 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09676 5. Hejnol, A. et al. Assessing the root of bilaterian animals with scalable phylogenomic methods. Proc. Biol. Sci. 276, 4261–4270 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2009.0896 6. Cannon, J. T. et al. Xenacoelomorpha is the sister group to Nephrozoa. Nature 530, 89–93 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16520 7. Laumer, C. E. et al. Revisiting metazoan phylogeny with genomic sampling of all phyla. Proc. Biol. Sci. 286, 20190831 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2019.0831 8. Philippe, H. et al. Mitigating anticipated effects of systematic errors supports sister-group relationship between Xenacoelomorpha and Ambulacraria. Curr. Biol. 29, 1818–1826.e6 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.04.009 9. Schiffer, P. H., Natsidis, P., Leite D. J., Robertson, H., Lapraz, F., Marlétaz, F., Fromm, B., Baudry, L., Simpson, F., Høye, E., Zakrzewski, A-C., Kapli, P., Hoff, K. J., Mueller, S., Marbouty, M., Marlow, H., Copley, R. R., Koszul, R., Sarkies, P. & Telford, M .J. The slow evolving genome of the xenacoelomorph worm Xenoturbella bocki. bioRxiv (2023), ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.24.497508 10. Suga, H. et al. The Capsaspora genome reveals a complex unicellular prehistory of animals. Nat. Commun. 4, 2325 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3325 11. Fernández, R. & Gabaldón, T. Gene gain and loss across the metazoan tree of life. Nat Ecol Evol 4, 524–533 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-019-1069-x | The slow evolving genome of the xenacoelomorph worm *Xenoturbella bocki* | Philipp H. Schiffer, Paschalis Natsidis, Daniel J. Leite, Helen Robertson, François Lapraz, Ferdinand Marlétaz, Bastian Fromm, Liam Baudry, Fraser Simpson, Eirik Høye, Anne-C. Zakrzewski, Paschalia Kapli, Katharina J. Hoff, Steven Mueller, Martial... | <p style="text-align: justify;">The evolutionary origins of Bilateria remain enigmatic. One of the more enduring proposals highlights similarities between a cnidarian-like planula larva and simple acoel-like flatworms. This idea is based in part o... |  | Evolutionary genomics | Rosa Fernández | 2022-11-01 12:31:53 | View | |

16 Dec 2022

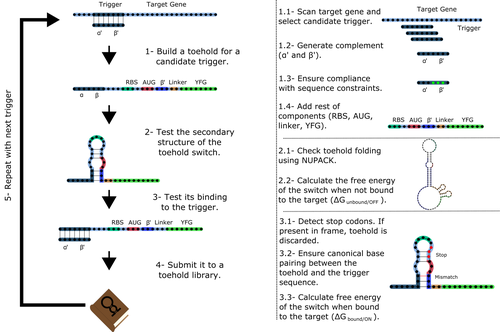

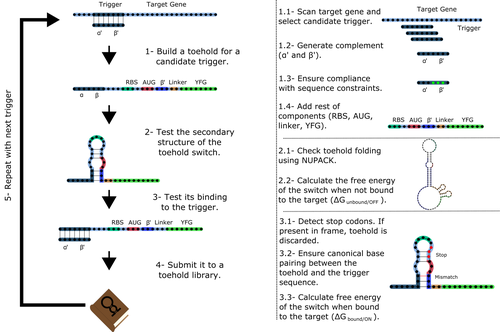

Toeholder: a Software for Automated Design and In Silico Validation of Toehold RiboswitchesAngel F. Cisneros, François D. Rouleau, Carla Bautista, Pascale Lemieux, Nathan Dumont-Leblond https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.09.467922A novel approach for engineering biological systems by interfacing computer science with synthetic biologyRecommended by Sahar Melamed based on reviews by Wim Wranken and 1 anonymous reviewerBiological systems depend on finely tuned interactions of their components. Thus, regulating these components is critical for the system's functionality. In prokaryotic cells, riboswitches are regulatory elements controlling transcription or translation. Riboswitches are RNA molecules that are usually located in the 5′-untranslated region of protein-coding genes. They generate secondary structures leading to the regulation of the expression of the downstream protein-coding gene (Kavita and Breaker, 2022). Riboswitches are very versatile and can bind a wide range of small molecules; in many cases, these are metabolic byproducts from the gene’s enzymatic or signaling pathway. Their versatility and abundance in many species make them attractive for synthetic biological circuits. One class that has been drawing the attention of synthetic biologists is toehold switches (Ekdahl et al., 2022; Green et al., 2014). These are single-stranded RNA molecules harboring the necessary elements for translation initiation of the downstream gene: a ribosome-binding site and a start codon. Conformation change of toehold switches is triggered by an RNA molecule, which enables translation. To exploit the most out of toehold switches, automation of their design would be highly advantageous. Cisneros and colleagues (Cisneros et al., 2022) developed a tool, “Toeholder”, that automates the design of toehold switches and performs in silico tests to select switch candidates for a target gene. Toeholder is an open-source tool that provides a comprehensive and automated workflow for the design of toehold switches. While web tools have been developed for designing toehold switches (To et al., 2018), Toeholder represents an intriguing approach to engineering biological systems by coupling synthetic biology with computational biology. Using molecular dynamics simulations, it identified the positions in the toehold switch where hydrogen bonds fluctuate the most. Identifying these regions holds great potential for modifications when refining the design of the riboswitches. To be effective, toehold switches should provide a strong ON signal and a weak OFF signal in the presence or the absence of a target, respectively. Toeholder nicely ranks the candidate toehold switches based on experimental evidence that correlates with toehold performance (based on good ON/OFF ratios). Riboswitches are highly appealing for a broad range of applications, including pharmaceutical and medical purposes (Blount and Breaker, 2006; Giarimoglou et al., 2022; Tickner and Farzan, 2021), thanks to their adaptability and inexpensiveness. The Toeholder tool developed by Cisneros and colleagues is expected to promote the implementation of toehold switches into these various applications. References Blount KF, Breaker RR (2006) Riboswitches as antibacterial drug targets. Nature Biotechnology, 24, 1558–1564. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt1268 Cisneros AF, Rouleau FD, Bautista C, Lemieux P, Dumont-Leblond N, ULaval 2019 T iGEM (2022) Toeholder: a Software for Automated Design and In Silico Validation of Toehold Riboswitches. bioRxiv, 2021.11.09.467922, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.09.467922 Ekdahl AM, Rojano-Nisimura AM, Contreras LM (2022) Engineering Toehold-Mediated Switches for Native RNA Detection and Regulation in Bacteria. Journal of Molecular Biology, 434, 167689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2022.167689 Giarimoglou N, Kouvela A, Maniatis A, Papakyriakou A, Zhang J, Stamatopoulou V, Stathopoulos C (2022) A Riboswitch-Driven Era of New Antibacterials. Antibiotics, 11, 1243. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11091243 Green AA, Silver PA, Collins JJ, Yin P (2014) Toehold Switches: De-Novo-Designed Regulators of Gene Expression. Cell, 159, 925–939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.002 Kavita K, Breaker RR (2022) Discovering riboswitches: the past and the future. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2022.08.009 Tickner ZJ, Farzan M (2021) Riboswitches for Controlled Expression of Therapeutic Transgenes Delivered by Adeno-Associated Viral Vectors. Pharmaceuticals, 14, 554. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14060554 To AC-Y, Chu DH-T, Wang AR, Li FC-Y, Chiu AW-O, Gao DY, Choi CHJ, Kong S-K, Chan T-F, Chan K-M, Yip KY (2018) A comprehensive web tool for toehold switch design. Bioinformatics, 34, 2862–2864. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty216 | Toeholder: a Software for Automated Design and In Silico Validation of Toehold Riboswitches | Angel F. Cisneros, François D. Rouleau, Carla Bautista, Pascale Lemieux, Nathan Dumont-Leblond | <p>Abstract: Synthetic biology aims to engineer biological circuits, which often involve gene expression. A particularly promising group of regulatory elements are riboswitches because of their versatility with respect to their targets, but e... |  | Bioinformatics | Sahar Melamed | 2022-02-16 14:40:13 | View |