Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * ▲ | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

22 May 2023

Genetic bases of resistance to the rice hoja blanca disease deciphered by a QTL approachAlexander Silva, Maria Elker Montoya, Constanza Quintero, Juan Cuasquer, Joe Tohme, Eduardo Graterol, Maribel Cruz, Mathias Lorieux https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.07.515427Scoring symptoms of a plant viral diseaseRecommended by Olivier Panaud based on reviews by Grégoire Aubert and Valérie GeffroyThe paper from Silva et al. (2023) provides new insights into the genetic bases of natural resistance of rice to the Rice Hoja Blanca (RHB) disease, one of its most serious diseases in tropical countries of the American continent and the Caribbean. This disease is caused by the Rice Hoja Blanca Virus, or RHBV, the vector of which is the planthopper insect Tagosodes orizicolus Müir. It is responsible for serious damage to the rice crop (Morales and Jennings 2010). The authors take a Quantitative Trait Loci (QTL) detection approach to find genomic regions statistically associated with the resistant phenotype. To this aim, they use four resistant x susceptible crosses (the susceptible parent being the same in all four crosses) to maximize the chances to find new QTLs. The F2 populations derived from the crosses are genotyped using Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) extracted from whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data of the resistant parents, and the F3 families derived from the F2 individuals are scored for disease symptoms. For this, they use a computer-aided image analysis protocol that they designed so they can estimate the severity of the damages in the plant. They find several new QTLs, some being apparently more associated with disease severity, others with disease incidence. They also find that a previously identified QTL of Oryza sativa ssp. japonica origin is also present in the indica cluster (Romero et al. 2014). Finally, they discuss the candidate genes that could underlie the QTLs and provide a simple model for resistance. It has to be noted that scoring symptoms of a viral disease such as RHB is very challenging. It requires maintaining populations of viruliferous insect vectors, mastering times and conditions for infestation by nymphs, and precise symptom scoring. It also requires the preparation of segregating populations, their genotyping with enough genetic markers, and mastering QTL detection methods. All these aspects are present in this work. In particular, the phenotyping of symptom severity implemented using computer-aided image processing represents an impressive, enormous amount of work. From the genomics side, the fine-scale genotyping is based on the WGS of the parental lines (resistant and susceptible), followed by the application of suitable bioinformatic tools for SNP extraction and primers prediction that can be used on their Fluidigm platform. It also required implementing data correction algorithms to achieve precise genetic maps in the four crosses. The QTL detection itself required careful statistical pre-processing of phenotypic data. The authors then used a combination of several QTL detection methods, including an original meta-QTL method they developed in the software MapDisto. The authors then perform a very complete and convincing analysis of candidate genes, which includes genes already identified for a similar disease (RSV) on chromosome 11 of rice. What remains to elucidate is whether the candidate genes are actually involved or not in the disease resistance process. The team has already started implementing gene knockout strategies to study some of them in more detail. It will be interesting to see whether those genes act against the virus itself, or against the insect vector. Overall the work is of high quality and represents an important advance in the knowledge of disease resistance. In addition, it has many implications for crop breeding, allowing the setup of large-scale, marker-assisted strategies, for new resistant elite varieties of rice. References Morales F and Jennings P (2010) Rice hoja blanca: a complex plant-virus-vector pathosystem. CAB Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1079/PAVSNNR20105043 Romero LE, Lozano I, Garavito A, et al (2014) Major QTLs control resistance to Rice hoja blanca virus and its vector Tagosodes orizicolus. G3 | Genes, Genomes, Genetics 4:133–142. https://doi.org/10.1534/g3.113.009373 Silva A, Montoya ME, Quintero C, Cuasquer J, Tohme J, Graterol E, Cruz M, Lorieux M (2023) Genetic bases of resistance to the rice hoja blanca disease deciphered by a QTL approach. bioRxiv, 2022.11.07.515427, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.07.515427 | Genetic bases of resistance to the rice hoja blanca disease deciphered by a QTL approach | Alexander Silva, Maria Elker Montoya, Constanza Quintero, Juan Cuasquer, Joe Tohme, Eduardo Graterol, Maribel Cruz, Mathias Lorieux | <p style="text-align: justify;">Rice hoja blanca (RHB) is one of the most serious diseases in rice growing areas in tropical Americas. Its causal agent is Rice hoja blanca virus (RHBV), transmitted by the planthopper <em>Tagosodes orizicolus </em>... |  | Functional genomics, Plants | Olivier Panaud | 2022-11-09 09:13:30 | View | |

20 Jul 2021

Genetic mapping of sex and self-incompatibility determinants in the androdioecious plant Phillyrea angustifoliaAmelie Carre, Sophie Gallina, Sylvain Santoni, Philippe Vernet, Cecile Gode, Vincent Castric, Pierre Saumitou-Laprade https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.15.439943Identification of distinct YX-like loci for sex determination and self-incompatibility in an androdioecious shrubRecommended by Tatiana Giraud and Ricardo C. Rodríguez de la Vega based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersA wide variety of systems have evolved to control mating compatibility in sexual organisms. Their genetic determinism and the factors controlling their evolution represent fascinating questions in evolutionary biology and genomics. The plant Phillyrea angustifolia (Oleaeceae family) represents an exciting model organism, as it displays two distinct and rare mating compatibility systems [1]: 1) males and hermaphrodites co-occur in populations of this shrub (a rare system called androdioecy), while the evolution and maintenance of purely hermaphroditic plants or mixtures of females and hermaphrodites (a system called gynodioecy) are easier to explain [2]; 2) a homomorphic diallelic self-incompatibility system acts in hermaphrodites, while such systems are usually multi-allelic, as rare alleles are advantageous, being compatible with all other alleles. Previous analyses of crosses brought some interesting answers to these puzzles, showing that males benefit from the ability to mate with all hermaphrodites regardless of their allele at the self-incompatibility system, and suggesting that both sex and self incompatibility are determined by XY-like genetic systems, i.e. with each a dominant allele; homozygotes for a single allele and heterozygotes therefore co-occur in natural populations at both sex and self-incompatibility loci [3]. Here, Carré et al. used genotyping-by-sequencing to build a genome linkage map of P. angustifolia [4]. The elegant and original use of a probabilistic model of segregating alleles (implemented in the SEX-DETector method) allowed to identify both the sex and self-incompatibility loci [4], while this tool was initially developed for detecting sex-linked genes in species with strictly separated sexes (dioecy) [5]. Carré et al. [4] confirmed that the sex and self-incompatibility loci are located in two distinct linkage groups and correspond to XY-like systems. A comparison with the genome of the closely related Olive tree indicated that their self-incompatibility systems were homologous. Such a XY-like system represents a rare genetic determination mechanism for self-incompatibility and has also been recently found to control mating types in oomycetes [6]. This study [4] paves the way for identifying the genes controlling the sex and self-incompatibility phenotypes and for understanding why and how self-incompatibility is only expressed in hermaphrodites and not in males. It will also be fascinating to study more finely the degree and extent of genomic differentiation at these two loci and to assess whether recombination suppression has extended stepwise away from the sex and self-incompatibility loci, as can be expected under some hypotheses, such as the sheltering of deleterious alleles near permanently heterozygous alleles [7]. Furthermore, the co-occurrence in P. angustifolia of sex and mating types can contribute to our understanding of the factor controlling their evolution [8]. References [1] Saumitou-Laprade P, Vernet P, Vassiliadis C, Hoareau Y, Magny G de, Dommée B, Lepart J (2010) A Self-Incompatibility System Explains High Male Frequencies in an Androdioecious Plant. Science, 327, 1648–1650. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1186687 [2] Pannell JR, Voillemot M (2015) Plant Mating Systems: Female Sterility in the Driver’s Seat. Current Biology, 25, R511–R514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.04.044 [3] Billiard S, Husse L, Lepercq P, Godé C, Bourceaux A, Lepart J, Vernet P, Saumitou-Laprade P (2015) Selfish male-determining element favors the transition from hermaphroditism to androdioecy. Evolution, 69, 683–693. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12613 [4] Carre A, Gallina S, Santoni S, Vernet P, Gode C, Castric V, Saumitou-Laprade P (2021) Genetic mapping of sex and self-incompatibility determinants in the androdioecious plant Phillyrea angustifolia. bioRxiv, 2021.04.15.439943, ver. 7 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.15.439943 [5] Muyle A, Käfer J, Zemp N, Mousset S, Picard F, Marais GA (2016) SEX-DETector: A Probabilistic Approach to Study Sex Chromosomes in Non-Model Organisms. Genome Biology and Evolution, 8, 2530–2543. https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evw172 [6] Dussert Y, Legrand L, Mazet ID, Couture C, Piron M-C, Serre R-F, Bouchez O, Mestre P, Toffolatti SL, Giraud T, Delmotte F (2020) Identification of the First Oomycete Mating-type Locus Sequence in the Grapevine Downy Mildew Pathogen, Plasmopara viticola. Current Biology, 30, 3897-3907.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.07.057 [7] Jay P, Tezenas E, Giraud T (2021) A deleterious mutation-sheltering theory for the evolution of sex chromosomes and supergenes. bioRxiv, 2021.05.17.444504. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.17.444504 [8] Billiard S, López-Villavicencio M, Devier B, Hood ME, Fairhead C, Giraud T (2011) Having sex, yes, but with whom? Inferences from fungi on the evolution of anisogamy and mating types. Biological Reviews, 86, 421–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-185X.2010.00153.x | Genetic mapping of sex and self-incompatibility determinants in the androdioecious plant Phillyrea angustifolia | Amelie Carre, Sophie Gallina, Sylvain Santoni, Philippe Vernet, Cecile Gode, Vincent Castric, Pierre Saumitou-Laprade | <p style="text-align: justify;">The diversity of mating and sexual systems in angiosperms is spectacular, but the factors driving their evolution remain poorly understood. In plants of the Oleaceae family, an unusual self-incompatibility (SI) syst... |  | Evolutionary genomics, Plants | Tatiana Giraud | 2021-05-04 10:37:26 | View | |

07 Aug 2023

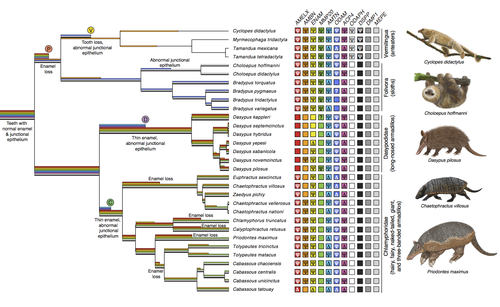

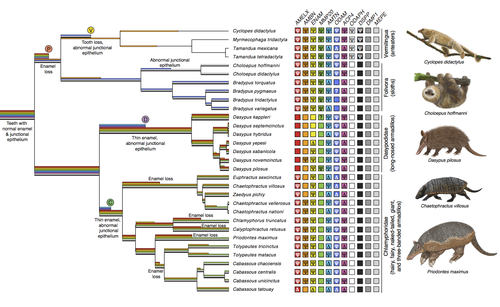

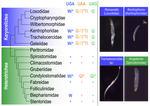

Genomic data suggest parallel dental vestigialization within the xenarthran radiationChristopher A Emerling, Gillian C Gibb, Marie-Ka Tilak, Jonathan J Hughes, Melanie Kuch, Ana T Duggan, Hendrik N Poinar, Michael W Nachman, Frederic Delsuc https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.09.519446What does dental gene decay tell us about the regressive evolution of teeth in South American mammals?Recommended by Didier Casane based on reviews by Juan C. Opazo, Régis Debruyne and Nicolas PolletA group of mammals, Xenathra, evolved and diversified in South America during its long period of isolation in the early to mid Cenozoic era. More recently, as a result of the Great Faunal Interchange between South America and North America, many xenarthran species went extinct. The thirty-one extant species belong to three groups: armadillos, sloths and anteaters. They share dental degeneration. However, the level of degeneration is variable. Anteaters entirely lack teeth, sloths have intermediately regressed teeth and most armadillos have a toothless premaxilla, as well as peg-like, single-rooted teeth that lack enamel in adult animals (Vizcaíno 2009). This diversity raises a number of questions about the evolution of dentition in these mammals. Unfortunately, the fossil record is too poor to provide refined information on the different stages of regressive evolution in these clades. In such cases, the identification of loss-of-function mutations and/or relaxed selection in genes related to a character regression can be very informative (Emerling and Springer 2014; Meredith et al. 2014; Policarpo et al. 2021). Indeed, shared and unique pseudogenes/relaxed selection can tell us to what extent regression has occurred in common ancestors and whether some changes are lineage-specific. In addition, the distribution of pseudogenes/relaxed selection on the branches of a phylogenetic tree is related to the evolutionary processes involved. A much higher density of pseudogenes in the most internal branches indicates that degeneration took place early and over a short period of time, consistent with selection against the presence of the morphological character with which they are associated, while pseudogenes distributed evenly in many internal and external branches suggest a more gradual process over many millions of years, in line with relaxed selection and fixation of loss-of-function mutations by genetic drift. In this paper (Emerling et al. 2023), the authors examined the dynamics of decay of 11 dental genes that may parallel teeth regression. The analyses of the data reported in this paper clearly point to xenarthran teeth having repeatedly regressed in parallel in the three clades. In fact, no loss-of-function mutation is shared by all species examined. However, more genes should be studied to confirm the hypothesis that the common ancestor of extant xenarthrans had normal dentition. There are distinct patterns of gene loss in different lineages that are associated with the variation in dentition observed across the clades. These patterns of gene loss suggest that regressive evolution took place both gradually and in relatively rapid, discrete phases during the diversification of xenarthrans. This study underscores the utility of using pseudogenes to reconstruct evolutionary history of morphological characters when fossils are sparse. References Emerling CA, Gibb GC, Tilak M-K, Hughes JJ, Kuch M, Duggan AT, Poinar HN, Nachman MW, Delsuc F. 2023. Genomic data suggest parallel dental vestigialization within the xenarthran radiation. bioRxiv, 2022.12.09.519446, ver 2, peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.09.519446 Emerling CA, Springer MS. 2014. Eyes underground: Regression of visual protein networks in subterranean mammals. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 78: 260-270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2014.05.016 Meredith RW, Zhang G, Gilbert MTP, Jarvis ED, Springer MS. 2014. Evidence for a single loss of mineralized teeth in the common avian ancestor. Science 346: 1254390. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1254390 Policarpo M, Fumey J, Lafargeas P, Naquin D, Thermes C, Naville M, Dechaud C, Volff J-N, Cabau C, Klopp C, et al. 2021. Contrasting gene decay in subterranean vertebrates: insights from cavefishes and fossorial mammals. Molecular Biology and Evolution 38: 589-605. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msaa249 Vizcaíno SF. 2009. The teeth of the “toothless”: novelties and key innovations in the evolution of xenarthrans (Mammalia, Xenarthra). Paleobiology 35: 343-366. https://doi.org/10.1666/0094-8373-35.3.343 | Genomic data suggest parallel dental vestigialization within the xenarthran radiation | Christopher A Emerling, Gillian C Gibb, Marie-Ka Tilak, Jonathan J Hughes, Melanie Kuch, Ana T Duggan, Hendrik N Poinar, Michael W Nachman, Frederic Delsuc | <p style="text-align: justify;">The recent influx of genomic data has provided greater insights into the molecular basis for regressive evolution, or vestigialization, through gene loss and pseudogenization. As such, the analysis of gene degradati... |  | Evolutionary genomics, Vertebrates | Didier Casane | 2022-12-12 16:01:57 | View | |

11 Mar 2021

Gut microbial ecology of Xenopus tadpoles across life stagesThibault Scalvenzi, Isabelle Clavereau, Mickael Bourge, Nicolas Pollet https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.25.110734A comprehensive look at Xenopus gut microbiota: effects of feed, developmental stages and parental transmissionRecommended by Wirulda Pootakham based on reviews by Vanessa Marcelino and 1 anonymous reviewerIt is well established that the gut microbiota play an important role in the overall health of their hosts (Jandhyala et al. 2015). To date, there are still a limited number of studies on the complex microbial communites inhabiting vertebrate digestive systems, especially the ones that also explored the functional diversity of the microbial community (Bletz et al. 2016). This preprint by Scalvenzi et al. (2021) reports a comprehensive study on the phylogenetic and metabolic profiles of the Xenopus gut microbiota. The author describes significant changes in the gut microbiome communities at different developmental stages and demonstrates different microbial community composition across organs. In addition, the study also investigates the impact of diet on the Xenopus tadpole gut microbiome communities as well as how the bacterial communities are transmitted from parents to the next generation. This is one of the first studies that addresses the interactions between gut bacteria and tadpoles during the development. The authors observe the dynamics of gut microbiome communities during tadpole growth and metamorphosis. They also explore host-gut microbial community metabolic interactions and demostrate the capacity of the microbiome to complement the metabolic pathways of the Xenopus genome. Although this study is limited by the use of Xenopus tadpoles in a laboratory, which are probably different from those in nature, I believe it still provides important and valuable information for the research community working on vertebrate’s microbiota and their interaction with the host. References Bletz et al. (2016). Amphibian gut microbiota shifts differentially in community structure but converges on habitat-specific predicted functions. Nature Communications, 7(1), 1-12. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms13699 Jandhyala, S. M., Talukdar, R., Subramanyam, C., Vuyyuru, H., Sasikala, M., & Reddy, D. N. (2015). Role of the normal gut microbiota. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG, 21(29), 8787. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748%2Fwjg.v21.i29.8787 Scalvenzi, T., Clavereau, I., Bourge, M. & Pollet, N. (2021) Gut microbial ecology of Xenopus tadpoles across life stages. bioRxiv, 2020.05.25.110734, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Geonmics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.25.110734 | Gut microbial ecology of Xenopus tadpoles across life stages | Thibault Scalvenzi, Isabelle Clavereau, Mickael Bourge, Nicolas Pollet | <p><strong>Background</strong> The microorganism world living in amphibians is still largely under-represented and under-studied in the literature. Among anuran amphibians, African clawed frogs of the Xenopus genus stand as well-characterized mode... |  | Evolutionary genomics, Metagenomics, Vertebrates | Wirulda Pootakham | 2020-05-25 14:01:19 | View | |

13 Jul 2024

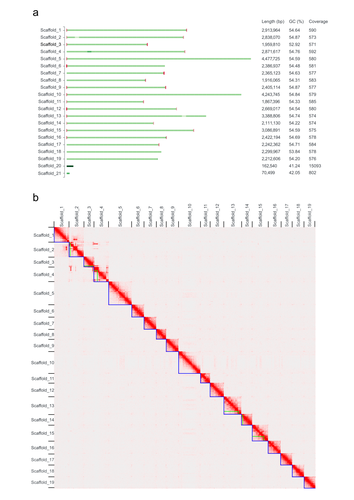

High quality genome assembly and annotation (v1) of the eukaryotic terrestrial microalga Coccomyxa viridis SAG 216-4Anton Kraege, Edgar Chavarro-Carrero, Nadège Guiglielmoni, Eva Schnell, Joseph Kirangwa, Stefanie Heilmann-Heimbach, Kerstin Becker, Karl Köhrer, Philipp Schiffer, Bart P. H. J. Thomma, Hanna Rovenich https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.11.548521Reference genome for the lichen-forming green alga Coccomyxa viridis SAG 216–4Recommended by Iker Irisarri based on reviews by Elisa Goldbecker, Fabian Haas and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Elisa Goldbecker, Fabian Haas and 2 anonymous reviewers

Green algae of the genus Coccomyxa (family Trebouxiophyceae) are extremely diverse in their morphology, habitat (i.e., in marine, freshwater, and terrestrial environments) and lifestyle, including free-living and mutualistic forms. Coccomyxa viridis (strain SAG 216–4) is a photobiont in the lichen Peltigera aphthosa, which was isolated in Switzerland more than 70 years ago (cf. SAG, the Culture Collection of Algae at the University of Göttingen, Germany). Despite the high diversity and plasticity in Coccomyxa, integrative taxonomic analyses led Darienko et al. (2015) to propose clear species boundaries. These authors also showed that symbiotic strains that form lichens evolved multiple times independently in Coccomyxa. Using state-of-the-art sequencing data and bioinformatic methods, including Pac-Bio HiFi and ONT long reads, as well as Hi-C chromatin conformation information, Kraege et al. (2024) generated a high-quality genome assembly for the Coccomyxa viridis strain SAG 216–4. They reconstructed 19 complete nuclear chromosomes, flanked by telomeric regions, totaling 50.9 Mb, plus the plastid and mitochondrial genomes. The performed quality controls leave no doubt of the high quality of the genome assemblies and structural annotations. An interesting observation is the lack of conserved synteny with the close relative Coccomyxa subellipsoidea, but further comparative studies with additional Coccomyxa strains will be required to grasp the genomic evolution in this genus of green algae. This project is framed within the ERGA pilot project, which aims to establish a pan-European genomics infrastructure and contribute to cataloging genomic biodiversity and producing resources that can inform conservation strategies (Formenti et al. 2022). This complete reference genome represents an important step towards this goal, in addition to contributing to future genomic analyses of Coccomyxa more generally.

References Darienko T, Gustavs L, Eggert A, Wolf W, Pröschold T (2015) Evaluating the species boundaries of green microalgae (Coccomyxa, Trebouxiophyceae, Chlorophyta) using integrative taxonomy and DNA barcoding with further implications for the species identification in environmental samples. PLOS ONE, 10, e0127838. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127838 Formenti G, Theissinger K, Fernandes C, Bista I, Bombarely A, Bleidorn C, Ciofi C, Crottini A, Godoy JA, Höglund J, Malukiewicz J, Mouton A, Oomen RA, Paez S, Palsbøll PJ, Pampoulie C, Ruiz-López MJ, Svardal H, Theofanopoulou C, de Vries J, Waldvogel A-M, Zhang G, Mazzoni CJ, Jarvis ED, Bálint M, European Reference Genome Atlas Consortium (2022) The era of reference genomes in conservation genomics. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 37, 197–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2021.11.008 Kraege A, Chavarro-Carrero EA, Guiglielmoni N, Schnell E, Kirangwa J, Heilmann-Heimbach S, Becker K, Köhrer K, WGGC Team, DeRGA Community, Schiffer P, Thomma BPHJ, Rovenich H (2024) High quality genome assembly and annotation (v1) of the eukaryotic terrestrial microalga Coccomyxa viridis SAG 216-4. bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.11.548521 | High quality genome assembly and annotation (v1) of the eukaryotic terrestrial microalga *Coccomyxa viridis* SAG 216-4 | Anton Kraege, Edgar Chavarro-Carrero, Nadège Guiglielmoni, Eva Schnell, Joseph Kirangwa, Stefanie Heilmann-Heimbach, Kerstin Becker, Karl Köhrer, Philipp Schiffer, Bart P. H. J. Thomma, Hanna Rovenich | <p>Unicellular green algae of the genus Coccomyxa are recognized for their worldwide distribution and ecological versatility. Most species described to date live in close association with various host species, such as in lichen associations. Howev... |  | ERGA Pilot | Iker Irisarri | 2023-11-09 11:54:43 | View | |

24 Jan 2024

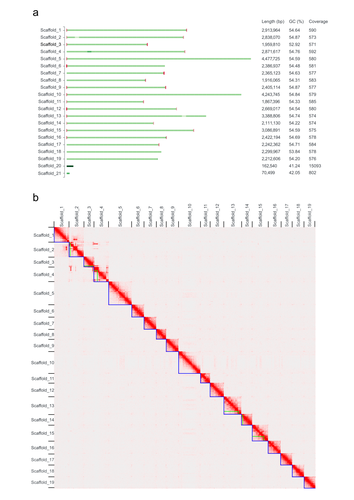

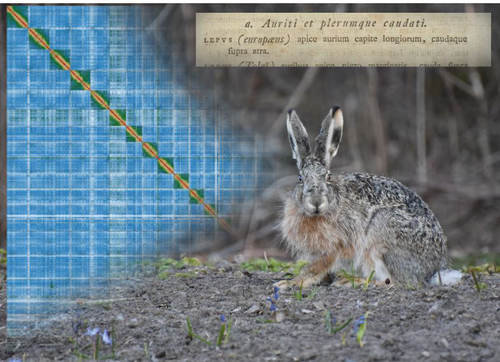

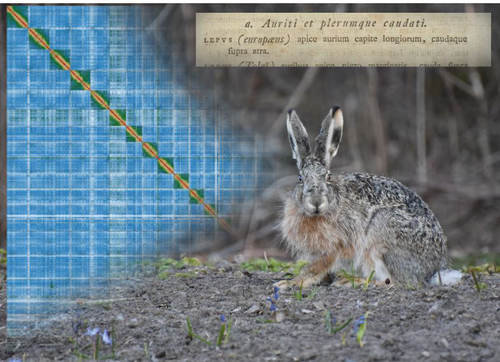

High quality genome assembly of the brown hare (Lepus europaeus) with chromosome-level scaffoldingCraig Michell, Joanna Collins, Pia K. Laine, Zsofia Fekete, Riikka Tapanainen, Jonathan M. D. Wood, Steffi Goffart, Jaakko L. O. Pohjoismaki https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.29.555262A high quality reference genome of the brown hareRecommended by Ed Hollox based on reviews by Merce Montoliu-Nerin and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Merce Montoliu-Nerin and 1 anonymous reviewer

The brown hare, or European hare, Lupus europaeus, is a widespread mammal whose natural range spans western Eurasia. At the northern limit of its range, it hybridises with the mountain hare (L. timidis), and humans have introduced it into other continents. It represents a particularly interesting mammal to study for its population genetics, extensive hybridisation zones, and as an invasive species. This study (Michell et al. 2024) has generated a high-quality assembly of a genome from a brown hare from Finland using long PacBio HiFi sequencing reads and Hi-C scaffolding. The contig N50 of this new genome is 43 Mb, and completeness, assessed using BUSCO, is 96.1%. The assembly comprises 23 autosomes, and an X chromosome and Y chromosome, with many chromosomes including telomeric repeats, indicating the high level of completeness of this assembly. While the genome of the mountain hare has previously been assembled, its assembly was based on a short-read shotgun assembly, with the rabbit as a reference genome. The new high-quality brown hare genome assembly allows a direct comparison with the rabbit genome assembly. For example, the assembly addresses the karyotype difference between the hare (n=24) and the rabbit (n=22). Chromosomes 12 and 17 of the hare are equivalent to chromosome 1 of the rabbit, and chromosomes 13 and 16 of the hare are equivalent to chromosome 2 of the rabbit. The new assembly also provides a hare Y-chromosome, as the previous mountain hare genome was from a female. This new genome assembly provides an important foundation for population genetics and evolutionary studies of lagomorphs. References Michell, C., Collins, J., Laine, P. K., Fekete, Z., Tapanainen, R., Wood, J. M. D., Goffart, S., Pohjoismäki, J. L. O. (2024). High quality genome assembly of the brown hare (Lepus europaeus) with chromosome-level scaffolding. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.29.555262 | High quality genome assembly of the brown hare (*Lepus europaeus*) with chromosome-level scaffolding | Craig Michell, Joanna Collins, Pia K. Laine, Zsofia Fekete, Riikka Tapanainen, Jonathan M. D. Wood, Steffi Goffart, Jaakko L. O. Pohjoismaki | <p style="text-align: justify;">We present here a high-quality genome assembly of the brown hare (Lepus europaeus Pallas), based on a fibroblast cell line of a male specimen from Liperi, Eastern Finland. This brown hare genome represents the first... |  | ERGA Pilot, Vertebrates | Ed Hollox | 2023-10-16 20:46:39 | View | |

13 Jul 2022

Karyorelict ciliates use an ambiguous genetic code with context-dependent stop/sense codonsBrandon Kwee Boon Seah, Aditi Singh, Estienne Carl Swart https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.12.488043An accident frozen in time: the ambiguous stop/sense genetic code of karyorelict ciliatesRecommended by Iker Irisarri based on reviews by Vittorio Boscaro and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Vittorio Boscaro and 2 anonymous reviewers

Several variations of the “universal” genetic code are known. Among the most striking are those where a codon can either encode for an amino acid or a stop signal depending on the context. Such ambiguous codes are known to have evolved in eukaryotes multiple times independently, particularly in ciliates – eight different codes have so far been discovered (1). We generally view such genetic codes are rare ‘variants’ of the standard code restricted to single species or strains, but this might as well reflect a lack of study of closely related species. In this study, Seah and co-authors (2) explore the possibility of codon reassignment in karyorelict ciliates closely related to Parduczia sp., which has been shown to contain an ambiguous genetic code (1). Here, single-cell transcriptomics are used, along with similar available data, to explore the possibility of codon reassignment across the diversity of Karyorelictea (four out of the six recognized families). Codon reassignments were inferred from their frequencies within conserved Pfam (3) protein domains, whereas stop codons were inferred from full-length transcripts with intact 3’-UTRs. Results show the reassignment of UAA and UAG stop codons to code for glutamine (Q) and the reassignment of the UGA stop codon into tryptophan (W). This occurs only within the coding sequences, whereas the end of transcription is marked by UGA as the main stop codon, and to a lesser extent by UAA. In agreement with a previous model proposed that explains the functioning of ambiguous codes (1,4), the authors observe a depletion of in-frame UGAs before the UGA codon that indicates the stop, thus avoiding premature termination of transcription. The inferred codon reassignments occur in all studied karyorelicts, including the previously studied Parduczia sp. Despite the overall clear picture, some questions remain. Data for two out of six main karyorelict lineages are so far absent and the available data for Cryptopharyngidae was inconclusive; the phylogenetic affinities of Cryptopharyngidae have also been questioned (5). This indicates the need for further study of this interesting group of organisms. As nicely discussed by the authors, experimental evidence could further strengthen the conclusions of this paper, including ribosome profiling, mass spectrometry – as done for Condylostoma (1) – or even direct genetic manipulation. The uniformity of the ambiguous genetic code across karyorelicts might at first seem dull, but when viewed in a phylogenetic context character distribution strongly suggest that this genetic code has an ancient origin in the karyorelict ancestor ~455 Ma in the Proterozoic (6). This ambiguous code is also not a rarity of some obscure species, but it is shared by ciliates that are very diverse and ecologically important. The origin of the karyorelict code is also intriguing. Adaptive arguments suggest that it could confer robustness to mutations causing premature stop codons. However, we lack evidence for ambiguous codes being linked to specific habitats of lifestyles that could account for it. Instead, the authors favor the neutral view of an ancient “frozen accident”, fixed stochastically simply because it did not pose a significant selective disadvantage. Once a stop codon is reassigned to an amino acid, it is increasingly difficult to revert this without the deleterious effect of prematurely terminating translation. At the end, the origin of the genetic code itself is thought to be a frozen accident too (7). References 1. Swart EC, Serra V, Petroni G, Nowacki M. Genetic codes with no dedicated stop codon: Context-dependent translation termination. Cell 2016;166: 691–702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.020 2. Seah BKB, Singh A, Swart EC (2022) Karyorelict ciliates use an ambiguous genetic code with context-dependent stop/sense codons. bioRxiv, 2022.04.12.488043. ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.12.488043 3. Mistry J, Chuguransky S, Williams L, Qureshi M, Salazar GA, Sonnhammer ELL, Tosatto SCE, Paladin L, Raj S, Richardson LJ, Finn RD, Bateman A. Pfam: The protein families database in 2021, Nuc Acids Res 2020;49: D412-D419. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa913 4. Alkalaeva E, Mikhailova T. Reassigning stop codons via translation termination: How a few eukaryotes broke the dogma. Bioessays. 2017;39. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.201600213 5. Xu Y, Li J, Song W, Warren A. Phylogeny and establishment of a new ciliate family, Wilbertomorphidae fam. nov. (Ciliophora, Karyorelictea), a highly specialized taxon represented by Wilbertomorpha colpoda gen. nov., spec. nov. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2013;60: 480–489. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeu.12055 6. Fernandes NM, Schrago CG. A multigene timescale and diversification dynamics of Ciliophora evolution. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2019;139: 106521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2019.106521 7. Crick FH. The origin of the genetic code. J Mol Biol. 1968;38: 367–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-2836(68)90392-6 | Karyorelict ciliates use an ambiguous genetic code with context-dependent stop/sense codons | Brandon Kwee Boon Seah, Aditi Singh, Estienne Carl Swart | <p style="text-align: justify;">In ambiguous stop/sense genetic codes, the stop codon(s) not only terminate translation but can also encode amino acids. Such codes have evolved at least four times in eukaryotes, twice among ciliates (<em>Condylost... |  | Bioinformatics, Evolutionary genomics | Iker Irisarri | 2022-05-02 11:06:10 | View | |

24 Feb 2023

MacSyFinder v2: Improved modelling and search engine to identify molecular systems in genomesBertrand Néron, Rémi Denise, Charles Coluzzi, Marie Touchon, Eduardo P. C. Rocha, Sophie S. Abby https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.02.506364A unique and customizable approach for functionally annotating prokaryotic genomesRecommended by Gavin Douglas based on reviews by Kwee Boon Brandon Seah and Max Emil Schön based on reviews by Kwee Boon Brandon Seah and Max Emil Schön

Macromolecular System Finder (MacSyFinder) v2 (Néron et al., 2023) is a newly updated approach for performing functional annotation of prokaryotic genomes (Abby et al., 2014). This tool parses an input file of protein sequences from a single genome (either ordered by genome location or unordered) and identifies the presence of specific cellular functions (referred to as “systems”). These systems are called based on two criteria: (1) that the "quorum" of a minimum set of core proteins involved is reached the “quorum” of a minimum set of core proteins being involved that are present, and (2) that the genes encoding these proteins are in the expected genomic organization (e.g., within the same order in an operon), when ordered data is provided. I believe the MacSyFinder approach represents an improvement over more commonly used methods exactly because it can incorporate such information on genomic organization, and also because it is more customizable. Before properly appreciating these points, it is worth noting the norms and key challenges surrounding high-throughput functional annotation of prokaryotic genomes. Genome sequences are being added to online repositories at increasing rates, which has led to an enormous amount of bacterial genome diversity available to investigate (Altermann et al., 2022). A key aspect of understanding this diversity is the functional annotation step, which enables genes to be grouped into more biologically interpretable categories. For instance, gene calls can be mapped against existing Clusters of Orthologous Genes, which are themselves grouped into general categories such as ‘Transcription’ and ‘Lipid metabolism’ (Galperin et al., 2021). This approach is valuable but is primarily used for global summaries of functional annotations within a genome: for example, it could be useful to know that a genome is particularly enriched for genes involved in lipid metabolism. However, knowing that a particular gene is involved in the general process of lipid metabolism is less likely to be actionable. In other words, the desired specificity of a gene’s functional annotation will depend on the exact question being investigated. There is no shortage of functional ontologies in genomics that can be applied for this purpose (Douglas and Langille, 2021), and researchers are often overwhelmed by the choice of which functional ontology to use. In this context, giving researchers the ability to precisely specify the gene families and operon structures they are interested in identifying across genomes provides useful control over what precise functions they are profiling. Of course, most researchers will lack the information and/or expertise to fully take advantage of MacSyFinder’s customizable features, but having this option for specialized purposes is valuable. The other MacSyFinder feature that I find especially noteworthy is that it can incorporate genomic organization (e.g., of genes ordered in operons) when calling systems. This is a rare feature among commonly used tools for functional annotation and likely results in much higher specificity. As the authors note, this capability makes the co-occurrence of paralogs, and other divergent genes that share sequence similarity, to contribute less noise (i.e., they result in fewer false positive calls). It is important to emphasize that these features are not new additions in MacSyFinder v2, but there are many other valuable changes. Most practically, this release is written in Python 3, rather than the obsolete Python 2.7, and was made more computationally efficient, which will enable MacSyFinder to be more widely used and more easily maintained moving forward. In addition, the search algorithm for analyzing individual proteins was fundamentally updated as well. The authors show that their improvements to the search algorithm result in an 8% and 20% increase in the number of identified calls for single and multi-locus secretion systems, respectively. Taken together, MacSyFinder v2 represents both practical and scientific improvements over the previous version, which will be of great value to the field. References Abby SS, Néron B, Ménager H, Touchon M, Rocha EPC (2014) MacSyFinder: A Program to Mine Genomes for Molecular Systems with an Application to CRISPR-Cas Systems. PLOS ONE, 9, e110726. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0110726 Altermann E, Tegetmeyer HE, Chanyi RM (2022) The evolution of bacterial genome assemblies - where do we need to go next? Microbiome Research Reports, 1, 15. https://doi.org/10.20517/mrr.2022.02 Douglas GM, Langille MGI (2021) A primer and discussion on DNA-based microbiome data and related bioinformatics analyses. Peer Community Journal, 1. https://doi.org/10.24072/pcjournal.2 Galperin MY, Wolf YI, Makarova KS, Vera Alvarez R, Landsman D, Koonin EV (2021) COG database update: focus on microbial diversity, model organisms, and widespread pathogens. Nucleic Acids Research, 49, D274–D281. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa1018 Néron B, Denise R, Coluzzi C, Touchon M, Rocha EPC, Abby SS (2023) MacSyFinder v2: Improved modelling and search engine to identify molecular systems in genomes. bioRxiv, 2022.09.02.506364, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.02.506364 | MacSyFinder v2: Improved modelling and search engine to identify molecular systems in genomes | Bertrand Néron, Rémi Denise, Charles Coluzzi, Marie Touchon, Eduardo P. C. Rocha, Sophie S. Abby | <p style="text-align: justify;">Complex cellular functions are usually encoded by a set of genes in one or a few organized genetic loci in microbial genomes. Macromolecular System Finder (MacSyFinder) is a program that uses these properties to mod... |  | Bacteria and archaea, Bioinformatics, Functional genomics | Gavin Douglas | Kwee Boon Brandon Seah, Max Emil Schön | 2022-09-09 10:30:31 | View |

23 Sep 2022

MATEdb, a data repository of high-quality metazoan transcriptome assemblies to accelerate phylogenomic studiesRosa Fernandez, Vanina Tonzo, Carolina Simon Guerrero, Jesus Lozano-Fernandez, Gemma I Martinez-Redondo, Pau Balart-Garcia, Leandro Aristide, Klara Eleftheriadi, Carlos Vargas-Chavez https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.18.500182MATEdb: a new phylogenomic-driven database for MetazoaRecommended by Samuel Abalde based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

The development (and standardization) of high-throughput sequencing techniques has revolutionized evolutionary biology, to the point that we almost see as normal fine-detail studies of genome architecture evolution (Robert et al., 2022), adaptation to new habitats (Rahi et al., 2019), or the development of key evolutionary novelties (Hilgers et al., 2018), to name three examples. One of the fields that has benefited the most is phylogenomics, i.e. the use of genome-wide data for inferring the evolutionary relationships among organisms. Dealing with such amount of data, however, has come with important analytical and computational challenges. Likewise, although the steady generation of genomic data from virtually any organism opens exciting opportunities for comparative analyses, it also creates a sort of “information fog”, where it is hard to find the most appropriate and/or the higher quality data. I have personally experienced this not so long ago, when I had to spend several weeks selecting the most complete transcriptomes from several phyla, moving back and forth between the NCBI SRA repository and the relevant literature. In an attempt to deal with this issue, some research labs have committed their time and resources to the generation of taxa- and topic-specific databases (Lathe et al., 2008), such as MolluscDB (Liu et al., 2021), focused on mollusk genomics, or EukProt (Richter et al., 2022), a protein repository representing the diversity of eukaryotes. A new database that promises to become an important resource in the near future is MATEdb (Fernández et al., 2022), a repository of high-quality genomic data from Metazoa. MATEdb has been developed from publicly available and newly generated transcriptomes and genomes, prioritizing quality over quantity. Upon download, the user has access to both raw data and the related datasets: assemblies, several quality metrics, the set of inferred protein-coding genes, and their annotation. Although it is clear to me that this repository has been created with phylogenomic analyses in mind, I see how it could be generalized to other related problems such as analyses of gene content or evolution of specific gene families. In my opinion, the main strengths of MATEdb are threefold:

On a negative note, I see two main drawbacks. First, as of today (September 16th, 2022) this database is in an early stage and it still needs to incorporate a lot of animal groups. This has been discussed during the revision process and the authors are already working on it, so it is only a matter of time until all major taxa are represented. Second, there is a scalability issue. In its current format it is not possible to select the taxa of interest and the full database has to be downloaded, which will become more and more difficult as it grows. Nonetheless, with the appropriate resources it would be easy to find a better solution. There are plenty of examples that could serve as inspiration, so I hope this does not become a big problem in the future. Altogether, I and the researchers that participated in the revision process believe that MATEdb has the potential to become an important and valuable addition to the metazoan phylogenomics community. Personally, I wish it was available just a few months ago, it would have saved me so much time. References Fernández R, Tonzo V, Guerrero CS, Lozano-Fernandez J, Martínez-Redondo GI, Balart-García P, Aristide L, Eleftheriadi K, Vargas-Chávez C (2022) MATEdb, a data repository of high-quality metazoan transcriptome assemblies to accelerate phylogenomic studies. bioRxiv, 2022.07.18.500182, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.18.500182 Hilgers L, Hartmann S, Hofreiter M, von Rintelen T (2018) Novel Genes, Ancient Genes, and Gene Co-Option Contributed to the Genetic Basis of the Radula, a Molluscan Innovation. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 35, 1638–1652. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy052 Lathe W, Williams J, Mangan M, Karolchik, D (2008). Genomic data resources: challenges and promises. Nature Education, 1(3), 2. Liu F, Li Y, Yu H, Zhang L, Hu J, Bao Z, Wang S (2021) MolluscDB: an integrated functional and evolutionary genomics database for the hyper-diverse animal phylum Mollusca. Nucleic Acids Research, 49, D988–D997. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa918 Rahi ML, Mather PB, Ezaz T, Hurwood DA (2019) The Molecular Basis of Freshwater Adaptation in Prawns: Insights from Comparative Transcriptomics of Three Macrobrachium Species. Genome Biology and Evolution, 11, 1002–1018. https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evz045 Richter DJ, Berney C, Strassert JFH, Poh Y-P, Herman EK, Muñoz-Gómez SA, Wideman JG, Burki F, Vargas C de (2022) EukProt: A database of genome-scale predicted proteins across the diversity of eukaryotes. bioRxiv, 2020.06.30.180687, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.30.180687 Robert NSM, Sarigol F, Zimmermann B, Meyer A, Voolstra CR, Simakov O (2022) Emergence of distinct syntenic density regimes is associated with early metazoan genomic transitions. BMC Genomics, 23, 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-022-08304-2 | MATEdb, a data repository of high-quality metazoan transcriptome assemblies to accelerate phylogenomic studies | Rosa Fernandez, Vanina Tonzo, Carolina Simon Guerrero, Jesus Lozano-Fernandez, Gemma I Martinez-Redondo, Pau Balart-Garcia, Leandro Aristide, Klara Eleftheriadi, Carlos Vargas-Chavez | <p style="text-align: justify;">With the advent of high throughput sequencing, the amount of genomic data available for animals (Metazoa) species has bloomed over the last decade, especially from transcriptomes due to lower sequencing costs and ea... |  | Bioinformatics, Evolutionary genomics, Functional genomics | Samuel Abalde | 2022-07-20 07:30:39 | View | |

02 Jun 2023

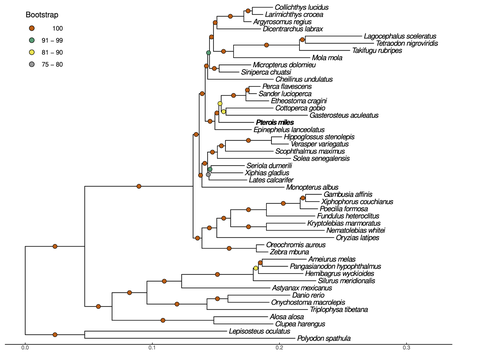

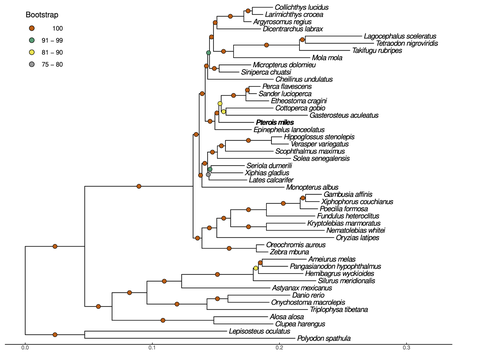

Near-chromosome level genome assembly of devil firefish, Pterois milesChristos V. Kitsoulis, Vasileios Papadogiannis, Jon B. Kristoffersen, Elisavet Kaitetzidou, Aspasia Sterioti, Costas S. Tsigenopoulos, Tereza Manousaki https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.01.10.523469The genome of a dangerous invader (fish) beautyRecommended by Iker Irisarri based on reviews by Maria Recuerda and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Maria Recuerda and 1 anonymous reviewer

High-quality genomes are currently being generated at an unprecedented speed powered by long-read sequencing technologies. However, sequencing effort is concentrated unequally across the tree of life and several key evolutionary and ecological groups remain largely unexplored. So is the case for fish species of the family Scorpaenidae (Perciformes). Kitsoulis et al. present the genome of the devil firefish, Pterois miles (1). Following current best practices, the assembly relies largely on Oxford Nanopore long reads, aided by Illumina short reads for polishing to increase the per-base accuracy. PacBio’s IsoSeq was used to sequence RNA from a variety of tissues as direct evidence for annotating genes. The reconstructed genome is 902 Mb in size and has high contiguity (N50=14.5 Mb; 660 scaffolds, 90% of the genome covered by the 83 longest scaffolds) and completeness (98% BUSCO completeness). The new genome is used to assess the phylogenetic position of P. miles, explore gene synteny against zebrafish, look at orthogroup expansion and contraction patterns in Perciformes, as well as to investigate the evolution of toxins in scorpaenid fish (2). In addition to its value for better understanding the evolution of scorpaenid and teleost fishes, this new genome is also an important resource for monitoring its invasiveness through the Mediterranean Sea (3) and the Atlantic Ocean, in the latter case forming the invasive lionfish complex with P. volitans (4). REFERENCES 1. Kitsoulis CV, Papadogiannis V, Kristoffersen JB, Kaitetzidou E, Sterioti E, Tsigenopoulos CS, Manousaki T. (2023) Near-chromosome level genome assembly of devil firefish, Pterois miles. BioRxiv, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.01.10.523469 2. Kiriake A, Shiomi K. (2011) Some properties and cDNA cloning of proteinaceous toxins from two species of lionfish (Pterois antennata and Pterois volitans). Toxicon, 58(6-7):494–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2011.08.010 3. Katsanevakis S, et al. (2020) Un- published Mediterranean records of marine alien and cryptogenic species. BioInvasions Records, 9:165–182. https://doi.org/10.3391/bir.2020.9.2.01 4. Lyons TJ, Tuckett QM, Hill JE. (2019) Data quality and quantity for invasive species: A case study of the lionfishes. Fish and Fisheries, 20:748–759. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12374 | Near-chromosome level genome assembly of devil firefish, *Pterois miles* | Christos V. Kitsoulis, Vasileios Papadogiannis, Jon B. Kristoffersen, Elisavet Kaitetzidou, Aspasia Sterioti, Costas S. Tsigenopoulos, Tereza Manousaki | <p style="text-align: justify;">Devil firefish (<em>Pterois miles</em>), a member of Scorpaenidae family, is one of the most successful marine non-native species, dominating around the world, that was rapidly spread into the Mediterranean Sea, thr... |  | Evolutionary genomics | Iker Irisarri | 2023-01-17 12:37:20 | View |