Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender▼ | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

23 Sep 2022

MATEdb, a data repository of high-quality metazoan transcriptome assemblies to accelerate phylogenomic studiesRosa Fernandez, Vanina Tonzo, Carolina Simon Guerrero, Jesus Lozano-Fernandez, Gemma I Martinez-Redondo, Pau Balart-Garcia, Leandro Aristide, Klara Eleftheriadi, Carlos Vargas-Chavez https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.18.500182MATEdb: a new phylogenomic-driven database for MetazoaRecommended by Samuel Abalde based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

The development (and standardization) of high-throughput sequencing techniques has revolutionized evolutionary biology, to the point that we almost see as normal fine-detail studies of genome architecture evolution (Robert et al., 2022), adaptation to new habitats (Rahi et al., 2019), or the development of key evolutionary novelties (Hilgers et al., 2018), to name three examples. One of the fields that has benefited the most is phylogenomics, i.e. the use of genome-wide data for inferring the evolutionary relationships among organisms. Dealing with such amount of data, however, has come with important analytical and computational challenges. Likewise, although the steady generation of genomic data from virtually any organism opens exciting opportunities for comparative analyses, it also creates a sort of “information fog”, where it is hard to find the most appropriate and/or the higher quality data. I have personally experienced this not so long ago, when I had to spend several weeks selecting the most complete transcriptomes from several phyla, moving back and forth between the NCBI SRA repository and the relevant literature. In an attempt to deal with this issue, some research labs have committed their time and resources to the generation of taxa- and topic-specific databases (Lathe et al., 2008), such as MolluscDB (Liu et al., 2021), focused on mollusk genomics, or EukProt (Richter et al., 2022), a protein repository representing the diversity of eukaryotes. A new database that promises to become an important resource in the near future is MATEdb (Fernández et al., 2022), a repository of high-quality genomic data from Metazoa. MATEdb has been developed from publicly available and newly generated transcriptomes and genomes, prioritizing quality over quantity. Upon download, the user has access to both raw data and the related datasets: assemblies, several quality metrics, the set of inferred protein-coding genes, and their annotation. Although it is clear to me that this repository has been created with phylogenomic analyses in mind, I see how it could be generalized to other related problems such as analyses of gene content or evolution of specific gene families. In my opinion, the main strengths of MATEdb are threefold:

On a negative note, I see two main drawbacks. First, as of today (September 16th, 2022) this database is in an early stage and it still needs to incorporate a lot of animal groups. This has been discussed during the revision process and the authors are already working on it, so it is only a matter of time until all major taxa are represented. Second, there is a scalability issue. In its current format it is not possible to select the taxa of interest and the full database has to be downloaded, which will become more and more difficult as it grows. Nonetheless, with the appropriate resources it would be easy to find a better solution. There are plenty of examples that could serve as inspiration, so I hope this does not become a big problem in the future. Altogether, I and the researchers that participated in the revision process believe that MATEdb has the potential to become an important and valuable addition to the metazoan phylogenomics community. Personally, I wish it was available just a few months ago, it would have saved me so much time. References Fernández R, Tonzo V, Guerrero CS, Lozano-Fernandez J, Martínez-Redondo GI, Balart-García P, Aristide L, Eleftheriadi K, Vargas-Chávez C (2022) MATEdb, a data repository of high-quality metazoan transcriptome assemblies to accelerate phylogenomic studies. bioRxiv, 2022.07.18.500182, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.18.500182 Hilgers L, Hartmann S, Hofreiter M, von Rintelen T (2018) Novel Genes, Ancient Genes, and Gene Co-Option Contributed to the Genetic Basis of the Radula, a Molluscan Innovation. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 35, 1638–1652. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy052 Lathe W, Williams J, Mangan M, Karolchik, D (2008). Genomic data resources: challenges and promises. Nature Education, 1(3), 2. Liu F, Li Y, Yu H, Zhang L, Hu J, Bao Z, Wang S (2021) MolluscDB: an integrated functional and evolutionary genomics database for the hyper-diverse animal phylum Mollusca. Nucleic Acids Research, 49, D988–D997. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa918 Rahi ML, Mather PB, Ezaz T, Hurwood DA (2019) The Molecular Basis of Freshwater Adaptation in Prawns: Insights from Comparative Transcriptomics of Three Macrobrachium Species. Genome Biology and Evolution, 11, 1002–1018. https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evz045 Richter DJ, Berney C, Strassert JFH, Poh Y-P, Herman EK, Muñoz-Gómez SA, Wideman JG, Burki F, Vargas C de (2022) EukProt: A database of genome-scale predicted proteins across the diversity of eukaryotes. bioRxiv, 2020.06.30.180687, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.30.180687 Robert NSM, Sarigol F, Zimmermann B, Meyer A, Voolstra CR, Simakov O (2022) Emergence of distinct syntenic density regimes is associated with early metazoan genomic transitions. BMC Genomics, 23, 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-022-08304-2 | MATEdb, a data repository of high-quality metazoan transcriptome assemblies to accelerate phylogenomic studies | Rosa Fernandez, Vanina Tonzo, Carolina Simon Guerrero, Jesus Lozano-Fernandez, Gemma I Martinez-Redondo, Pau Balart-Garcia, Leandro Aristide, Klara Eleftheriadi, Carlos Vargas-Chavez | <p style="text-align: justify;">With the advent of high throughput sequencing, the amount of genomic data available for animals (Metazoa) species has bloomed over the last decade, especially from transcriptomes due to lower sequencing costs and ea... |  | Bioinformatics, Evolutionary genomics, Functional genomics | Samuel Abalde | 2022-07-20 07:30:39 | View | |

16 Dec 2022

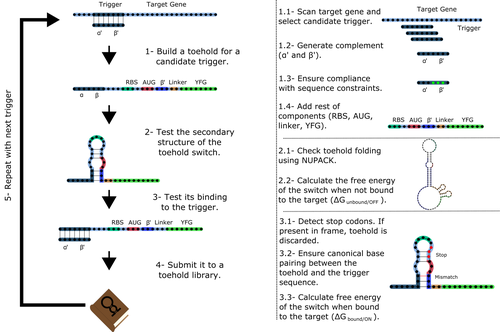

Toeholder: a Software for Automated Design and In Silico Validation of Toehold RiboswitchesAngel F. Cisneros, François D. Rouleau, Carla Bautista, Pascale Lemieux, Nathan Dumont-Leblond https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.09.467922A novel approach for engineering biological systems by interfacing computer science with synthetic biologyRecommended by Sahar Melamed based on reviews by Wim Wranken and 1 anonymous reviewerBiological systems depend on finely tuned interactions of their components. Thus, regulating these components is critical for the system's functionality. In prokaryotic cells, riboswitches are regulatory elements controlling transcription or translation. Riboswitches are RNA molecules that are usually located in the 5′-untranslated region of protein-coding genes. They generate secondary structures leading to the regulation of the expression of the downstream protein-coding gene (Kavita and Breaker, 2022). Riboswitches are very versatile and can bind a wide range of small molecules; in many cases, these are metabolic byproducts from the gene’s enzymatic or signaling pathway. Their versatility and abundance in many species make them attractive for synthetic biological circuits. One class that has been drawing the attention of synthetic biologists is toehold switches (Ekdahl et al., 2022; Green et al., 2014). These are single-stranded RNA molecules harboring the necessary elements for translation initiation of the downstream gene: a ribosome-binding site and a start codon. Conformation change of toehold switches is triggered by an RNA molecule, which enables translation. To exploit the most out of toehold switches, automation of their design would be highly advantageous. Cisneros and colleagues (Cisneros et al., 2022) developed a tool, “Toeholder”, that automates the design of toehold switches and performs in silico tests to select switch candidates for a target gene. Toeholder is an open-source tool that provides a comprehensive and automated workflow for the design of toehold switches. While web tools have been developed for designing toehold switches (To et al., 2018), Toeholder represents an intriguing approach to engineering biological systems by coupling synthetic biology with computational biology. Using molecular dynamics simulations, it identified the positions in the toehold switch where hydrogen bonds fluctuate the most. Identifying these regions holds great potential for modifications when refining the design of the riboswitches. To be effective, toehold switches should provide a strong ON signal and a weak OFF signal in the presence or the absence of a target, respectively. Toeholder nicely ranks the candidate toehold switches based on experimental evidence that correlates with toehold performance (based on good ON/OFF ratios). Riboswitches are highly appealing for a broad range of applications, including pharmaceutical and medical purposes (Blount and Breaker, 2006; Giarimoglou et al., 2022; Tickner and Farzan, 2021), thanks to their adaptability and inexpensiveness. The Toeholder tool developed by Cisneros and colleagues is expected to promote the implementation of toehold switches into these various applications. References Blount KF, Breaker RR (2006) Riboswitches as antibacterial drug targets. Nature Biotechnology, 24, 1558–1564. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt1268 Cisneros AF, Rouleau FD, Bautista C, Lemieux P, Dumont-Leblond N, ULaval 2019 T iGEM (2022) Toeholder: a Software for Automated Design and In Silico Validation of Toehold Riboswitches. bioRxiv, 2021.11.09.467922, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.09.467922 Ekdahl AM, Rojano-Nisimura AM, Contreras LM (2022) Engineering Toehold-Mediated Switches for Native RNA Detection and Regulation in Bacteria. Journal of Molecular Biology, 434, 167689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2022.167689 Giarimoglou N, Kouvela A, Maniatis A, Papakyriakou A, Zhang J, Stamatopoulou V, Stathopoulos C (2022) A Riboswitch-Driven Era of New Antibacterials. Antibiotics, 11, 1243. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11091243 Green AA, Silver PA, Collins JJ, Yin P (2014) Toehold Switches: De-Novo-Designed Regulators of Gene Expression. Cell, 159, 925–939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.002 Kavita K, Breaker RR (2022) Discovering riboswitches: the past and the future. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2022.08.009 Tickner ZJ, Farzan M (2021) Riboswitches for Controlled Expression of Therapeutic Transgenes Delivered by Adeno-Associated Viral Vectors. Pharmaceuticals, 14, 554. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14060554 To AC-Y, Chu DH-T, Wang AR, Li FC-Y, Chiu AW-O, Gao DY, Choi CHJ, Kong S-K, Chan T-F, Chan K-M, Yip KY (2018) A comprehensive web tool for toehold switch design. Bioinformatics, 34, 2862–2864. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty216 | Toeholder: a Software for Automated Design and In Silico Validation of Toehold Riboswitches | Angel F. Cisneros, François D. Rouleau, Carla Bautista, Pascale Lemieux, Nathan Dumont-Leblond | <p>Abstract: Synthetic biology aims to engineer biological circuits, which often involve gene expression. A particularly promising group of regulatory elements are riboswitches because of their versatility with respect to their targets, but e... |  | Bioinformatics | Sahar Melamed | 2022-02-16 14:40:13 | View | |

22 Nov 2023

The slow evolving genome of the xenacoelomorph worm Xenoturbella bockiPhilipp H. Schiffer, Paschalis Natsidis, Daniel J. Leite, Helen Robertson, François Lapraz, Ferdinand Marlétaz, Bastian Fromm, Liam Baudry, Fraser Simpson, Eirik Høye, Anne-C. Zakrzewski, Paschalia Kapli, Katharina J. Hoff, Steven Mueller, Martial Marbouty, Heather Marlow, Richard R. Copley, Romain Koszul, Peter Sarkies, Maximilian J. Telford https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.24.497508Genomic idiosyncrasies of Xenoturbella bocki: morphologically simple yet genetically complexRecommended by Rosa Fernández based on reviews by Christopher Laumer and 1 anonymous reviewerXenoturbella is a genus of morphologically simple bilaterians inhabiting benthic environments. Until very recently, only one species was known from the genus, Xenoturbella bocki Westblad 1949 [1]. Less than a decade ago, five more species were discovered (X. churro, X. monstrosa, X. profunda, X. hollandorum [2] and X. japonica [3]). These enigmatic animals lack an anus, a coelom, reproductive organs, nephrocytes and a centralized nervous system [1]. The systematic classification of the genus has substantially changed in the last decades, with first being considered as its own phylum (Xenoturbellida) and then being clustered together with acoels and nemertodermatids into the phylum Xenacoelomorpha [4,5]. The phylogenetic position of the xenacoelomorphs has been recalcitrant to resolution, with its position ranging from being the sister group to Nephrozoa (ie, protostomes and deuterostomes [6]) to the sister group to Ambulacraria (ie, Hemichordata and Echinodermata) in a clade called Xenambulacraria [4]. Recent studies based on expanded datasets and more refined analyses support either topology [7,8]. Either way, it is clear that additional studies on Xenoturbella could provide important insights into the origins of bilaterian traits such as the anus, the nephrons and the evolution of a centralized nervous system.

In any case, we are approaching a qualitative jump in how we understand phylogenomics thanks to efforts derived from the availability of chromosome-level genome assemblies for a growing number of species. Exciting times are ahead for us, evolutionary biologists, to explore what high-quality genomes - in combination with multiomics datasets - will reveal about animal evolution. I am personally really looking forward to it. References 1. Westblad E. (1949). Xenoturbella bocki n.g., n.sp., a peculiar, primitive Turbellarian type. Arkiv för Zoologi 1, 3-29 (1949). 2. Rouse, G. W., Wilson, N. G., Carvajal, J. I. & Vrijenhoek, R. C. New deep-sea species of Xenoturbella and the position of Xenacoelomorpha. Nature 530, 94–97 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16545 3. Nakano, H. et al. Correction to: A new species of Xenoturbella from the western Pacific Ocean and the evolution of Xenoturbella. BMC Evol. Biol. 18, 1–2 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-018-1190-5https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-018-1190-5 4. Philippe, H. et al. Acoelomorph flatworms are deuterostomes related to Xenoturbella. Nature 470, 255–258 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09676 5. Hejnol, A. et al. Assessing the root of bilaterian animals with scalable phylogenomic methods. Proc. Biol. Sci. 276, 4261–4270 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2009.0896 6. Cannon, J. T. et al. Xenacoelomorpha is the sister group to Nephrozoa. Nature 530, 89–93 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16520 7. Laumer, C. E. et al. Revisiting metazoan phylogeny with genomic sampling of all phyla. Proc. Biol. Sci. 286, 20190831 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2019.0831 8. Philippe, H. et al. Mitigating anticipated effects of systematic errors supports sister-group relationship between Xenacoelomorpha and Ambulacraria. Curr. Biol. 29, 1818–1826.e6 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.04.009 9. Schiffer, P. H., Natsidis, P., Leite D. J., Robertson, H., Lapraz, F., Marlétaz, F., Fromm, B., Baudry, L., Simpson, F., Høye, E., Zakrzewski, A-C., Kapli, P., Hoff, K. J., Mueller, S., Marbouty, M., Marlow, H., Copley, R. R., Koszul, R., Sarkies, P. & Telford, M .J. The slow evolving genome of the xenacoelomorph worm Xenoturbella bocki. bioRxiv (2023), ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.24.497508 10. Suga, H. et al. The Capsaspora genome reveals a complex unicellular prehistory of animals. Nat. Commun. 4, 2325 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3325 11. Fernández, R. & Gabaldón, T. Gene gain and loss across the metazoan tree of life. Nat Ecol Evol 4, 524–533 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-019-1069-x | The slow evolving genome of the xenacoelomorph worm *Xenoturbella bocki* | Philipp H. Schiffer, Paschalis Natsidis, Daniel J. Leite, Helen Robertson, François Lapraz, Ferdinand Marlétaz, Bastian Fromm, Liam Baudry, Fraser Simpson, Eirik Høye, Anne-C. Zakrzewski, Paschalia Kapli, Katharina J. Hoff, Steven Mueller, Martial... | <p style="text-align: justify;">The evolutionary origins of Bilateria remain enigmatic. One of the more enduring proposals highlights similarities between a cnidarian-like planula larva and simple acoel-like flatworms. This idea is based in part o... |  | Evolutionary genomics | Rosa Fernández | 2022-11-01 12:31:53 | View | |

08 Apr 2022

POSTPRINT

Phylogenetics in the Genomic EraCéline Scornavacca, Frédéric Delsuc, Nicolas Galtier https://hal.inria.fr/PGE/“Phylogenetics in the Genomic Era” brings together experts in the field to present a comprehensive synthesisRecommended by Robert Waterhouse and Karen MeusemannE-book: Phylogenetics in the Genomic Era (Scornavacca et al. 2021) This book was not peer-reviewed by PCI Genomics. It has undergone an internal review by the editors. Accurate reconstructions of the relationships amongst species and the genes encoded in their genomes are an essential foundation for almost all evolutionary inferences emerging from downstream analyses. Molecular phylogenetics has developed as a field over many decades to build suites of models and methods to reconstruct reliable trees that explain, support, or refute such inferences. The genomic era has brought new challenges and opportunities to the field, opening up new areas of research and algorithm development to take advantage of the accumulating large-scale data. Such ‘big-data’ phylogenetics has come to be known as phylogenomics, which broadly aims to connect molecular and evolutionary biology research to address questions centred on relationships amongst taxa, mechanisms of molecular evolution, and the biological functions of genes and other genomic elements. This book brings together experts in the field to present a comprehensive synthesis of Phylogenetics in the Genomic Era, covering key conceptual and methodological aspects of how to build accurate phylogenies and how to apply them in molecular and evolutionary research. The paragraphs below briefly summarise the five constituent parts of the book, highlighting the key concepts, methods, and applications that each part addresses. Being organised in an accessible style, while presenting details to provide depth where necessary, and including guides describing real-world examples of major phylogenomic tools, this collection represents an invaluable resource, particularly for students and newcomers to the field of phylogenomics. Part 1: Phylogenetic analyses in the genomic era Modelling how sequences evolve is a fundamental cornerstone of phylogenetic reconstructions. This part of the book introduces the reader to phylogenetic inference methods and algorithmic optimisations in the contexts of Markov, Maximum Likelihood, and Bayesian models of sequence evolution. The main concepts and theoretical considerations are mapped out for probabilistic Markov models, efficient tree building with Maximum Likelihood methods, and the flexibility and robustness of Bayesian approaches. These are supported with practical examples of phylogenomic applications using the popular tools RAxML and PhyloBayes. By considering theoretical, algorithmic, and practical aspects, these chapters provide readers with a holistic overview of the challenges and recent advances in developing scalable phylogenetic analyses in the genomic era. Part 2: Data quality, model adequacy This part focuses on the importance of considering the appropriateness of the evolutionary models used and the accuracy of the underlying molecular and genomic data. Both these aspects can profoundly affect the results when applying current phylogenomic methods to make inferences about complex biological and evolutionary processes. A clear example is presented for methods for building multiple sequence alignments and subsequent filtering approaches that can greatly impact phylogeny inference. The importance of error detection in (meta)barcode sequencing data is also highlighted, with solutions offered by the MACSE_BARCODE pipeline for accurate taxonomic assignments. Orthology datasets are essential markers for phylogenomic inferences, but the overview of concepts and methods presented shows that they too face challenges with respect to model selection and data quality. Finally, an innovative approach using ancestral gene order reconstructions provides new perspectives on how to assess gene tree accuracy for phylogenomic analyses. By emphasising through examples the importance of using appropriate evolutionary models and assessing input data quality, these chapters alert readers to key limitations that the field as a whole strives to address. Part 3: Resolving phylogenomic conflicts Conflicting phylogenetic signals are commonplace and may derive from statistical or systematic bias. This part of the book addresses possible causes of conflict, discordance between gene trees and species trees and how processes that lead to such conflicts can be described by phylogenetic models. Furthermore, it provides an overview of various models and methods with examples in phylogenomics including their pros and cons. Outlined in detail is the multispecies coalescent model (MSC) and its applications in phylogenomics. An interesting aspect is that different phylogenetic signals leading to conflict are in fact a key source of information rather than a problem that can – and should – be used to point to events like introgression or hybridisation, highlighting possible future trends in this research area. Last but not least, this part of the book also addresses inferring species trees by concatenating single multiple sequence alignments (gene alignments) versus inferring the species tree based on ensembles of single gene trees pointing out advantages and disadvantages of both approaches. As an important take home message from these chapters, it is recommended to be flexible and identify the most appropriate approach for each dataset to be analysed since this may tremendously differ depending on the dataset, setting, taxa, and phylogenetic level addressed by the researcher. Part 4: Functional evolutionary genomics In this part of the book the focus shifts to functional considerations of phylogenomics approaches both in terms of molecular evolution and adaptation and with respect to gene expression. The utility of multi-species analysis is clearly presented in the context of annotating functional genomic elements through quantifying evolutionary constraint and protein-coding potential. An historical perspective on characterising rates of change highlights how phylogenomic datasets help to understand the modes of molecular evolution across the genome, over time, and between lineages. These are contextualised with respect to the specific aim of detecting signatures of adaptation from protein-coding DNA alignments using the example of the MutSelDP-ω∗ model. This is extended with the presentation of the generally rare case of adaptive sequence convergence, where consideration of appropriate models and knowledge of gene functions and phenotypic effects are needed. Constrained or relaxed, selection pressures on sequence or copy-number affect genomic elements in different ways, making the very concept of function difficult to pin down despite it being fundamental to relate the genome to the phenotype and organismal fitness. Here gene expression provides a measurable intermediate, for which the Expression Comparison tool from the Bgee suite allows exploration of expression patterns across multiple animal species taking into account anatomical homology. Overall, phylogenomics applications in functional evolutionary genomics build on a rich theoretical history from molecular analyses where integration with knowledge of gene functions is challenging but critical. Part 5: Phylogenomic applications Rather than attempting to review the full extent of applications linked to phylogenomics, this part of the book focuses on providing detailed specific insights into selected examples and methods concerning i) estimating divergence times, and ii) species delimitation in the era of ‘omics’ data. With respect to estimating divergence times, an exemplary overview is provided for fossil data recovered from geological records, either using fossil data as calibration points with an extant-species-inferred phylogeny, or using a fossilised birth-death process as a mechanistic model that accounts for lineage diversification. Included is a tutorial for a joint approach to infer phylogenies and estimate divergence times using the RevBayes software with various models implemented for different applications and datasets incorporating molecular and morphological data. An interesting excursion is outlined focusing on timescale estimates with respect to viral evolution introducing BEAGLE, a high-performance likelihood-calculation platform that can be used on multi-core systems. As a second major subject, species delimitation is addressed since currently the increasing amount of available genomic data enables extensive inferences, for instance about the degree of genetic isolation among species and ancient and recent introgression events. Describing the history of molecular species delimitation up to the current genomic era and presenting widely used computational methods incorporating single- and multi-locus genomic data, pros and cons are addressed. Finally, a proposal for a new method for delimiting species based on empirical criteria is outlined. In the closing chapter of this part of the book, BPP (Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo program) for analysing multi-locus sequence data under the multispecies coalescent (MSC) model with and without introgression is introduced, including a tutorial. These examples together provide accessible details on key conceptual and methodological aspects related to the application of phylogenetics in the genomic era. References Scornavacca C, Delsuc F, Galtier N (2021) Phylogenetics in the Genomic Era. https://hal.inria.fr/PGE/ | Phylogenetics in the Genomic Era | Céline Scornavacca, Frédéric Delsuc, Nicolas Galtier | <p style="text-align: justify;">Molecular phylogenetics was born in the middle of the 20th century, when the advent of protein and DNA sequencing offered a novel way to study the evolutionary relationships between living organisms. The first 50 ye... |  | Bacteria and archaea, Bioinformatics, Evolutionary genomics, Functional genomics, Fungi, Plants, Population genomics, Vertebrates, Viruses and transposable elements | Robert Waterhouse | 2022-03-15 17:43:52 | View | |

18 Jul 2022

CulebrONT: a streamlined long reads multi-assembler pipeline for prokaryotic and eukaryotic genomesJulie Orjuela, Aurore Comte, Sébastien Ravel, Florian Charriat, Tram Vi, Francois Sabot, Sébastien Cunnac https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.19.452922A flexible and reproducible pipeline for long-read assembly and evaluationRecommended by Raúl Castanera based on reviews by Benjamin Istace and Valentine MurigneuxThird-generation sequencing has revolutionised de novo genome assembly. Thanks to this technology, genome reference sequences have evolved from fragmented drafts to gapless, telomere-to-telomere genome assemblies. Long reads produced by Oxford Nanopore and PacBio technologies can span structural variants and resolve complex repetitive regions such as centromeres, unlocking previously inaccessible genomic information. Nowadays, many research groups can afford to sequence the genome of their working model using long reads. Nevertheless, genome assembly poses a significant computational challenge. Read length, quality, coverage and genomic features such as repeat content can affect assembly contiguity, accuracy, and completeness in almost unpredictable ways. Consequently, there is no best universal software or protocol for this task. Producing a high-quality assembly requires chaining several tools into pipelines and performing extensive comparisons between the assemblies obtained by different tool combinations to decide which one is the best. This task can be extremely challenging, as the number of tools available rises very rapidly, and thorough benchmarks cannot be updated and published at such a fast pace. In their paper, Orjuela and collaborators present CulebrONT [1], a universal pipeline that greatly contributes to overcoming these challenges and facilitates long-read genome assembly for all taxonomic groups. CulebrONT incorporates six commonly used assemblers and allows to perform assembly, circularization (if needed), polishing, and evaluation in a simple framework. One important aspect of CulebrONT is its modularity, which allows the activation or deactivation of specific tools, giving great flexibility to the user. Nevertheless, possibly the best feature of CulebrONT is the opportunity to benchmark the selected tool combinations based on the excellent report generated by the pipeline. This HTML report aggregates the output of several tools for quality evaluation of the assemblies (e.g. BUSCO [2] or QUAST [3]) generated by the different assemblers, in addition to the running time and configuration parameters. Such information is of great help to identify the best-suited pipeline, as exemplified by the authors using four datasets of different taxonomic origins. Finally, CulebrONT can handle multiple samples in parallel, which makes it a good solution for laboratories looking for multiple assemblies on a large scale. References 1. Orjuela J, Comte A, Ravel S, Charriat F, Vi T, Sabot F, Cunnac S (2022) CulebrONT: a streamlined long reads multi-assembler pipeline for prokaryotic and eukaryotic genomes. bioRxiv, 2021.07.19.452922, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.19.452922 2. Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM (2015) BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics, 31, 3210–3212. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351 3. Gurevich A, Saveliev V, Vyahhi N, Tesler G (2013) QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics, 29, 1072–1075. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086 | CulebrONT: a streamlined long reads multi-assembler pipeline for prokaryotic and eukaryotic genomes | Julie Orjuela, Aurore Comte, Sébastien Ravel, Florian Charriat, Tram Vi, Francois Sabot, Sébastien Cunnac | <p style="text-align: justify;">Using long reads provides higher contiguity and better genome assemblies. However, producing such high quality sequences from raw reads requires to chain a growing set of tools, and determining the best workflow is ... |  | Bioinformatics | Raúl Castanera | Valentine Murigneux | 2022-02-22 16:21:25 | View |

22 May 2023

Genetic bases of resistance to the rice hoja blanca disease deciphered by a QTL approachAlexander Silva, Maria Elker Montoya, Constanza Quintero, Juan Cuasquer, Joe Tohme, Eduardo Graterol, Maribel Cruz, Mathias Lorieux https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.07.515427Scoring symptoms of a plant viral diseaseRecommended by Olivier Panaud based on reviews by Grégoire Aubert and Valérie GeffroyThe paper from Silva et al. (2023) provides new insights into the genetic bases of natural resistance of rice to the Rice Hoja Blanca (RHB) disease, one of its most serious diseases in tropical countries of the American continent and the Caribbean. This disease is caused by the Rice Hoja Blanca Virus, or RHBV, the vector of which is the planthopper insect Tagosodes orizicolus Müir. It is responsible for serious damage to the rice crop (Morales and Jennings 2010). The authors take a Quantitative Trait Loci (QTL) detection approach to find genomic regions statistically associated with the resistant phenotype. To this aim, they use four resistant x susceptible crosses (the susceptible parent being the same in all four crosses) to maximize the chances to find new QTLs. The F2 populations derived from the crosses are genotyped using Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) extracted from whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data of the resistant parents, and the F3 families derived from the F2 individuals are scored for disease symptoms. For this, they use a computer-aided image analysis protocol that they designed so they can estimate the severity of the damages in the plant. They find several new QTLs, some being apparently more associated with disease severity, others with disease incidence. They also find that a previously identified QTL of Oryza sativa ssp. japonica origin is also present in the indica cluster (Romero et al. 2014). Finally, they discuss the candidate genes that could underlie the QTLs and provide a simple model for resistance. It has to be noted that scoring symptoms of a viral disease such as RHB is very challenging. It requires maintaining populations of viruliferous insect vectors, mastering times and conditions for infestation by nymphs, and precise symptom scoring. It also requires the preparation of segregating populations, their genotyping with enough genetic markers, and mastering QTL detection methods. All these aspects are present in this work. In particular, the phenotyping of symptom severity implemented using computer-aided image processing represents an impressive, enormous amount of work. From the genomics side, the fine-scale genotyping is based on the WGS of the parental lines (resistant and susceptible), followed by the application of suitable bioinformatic tools for SNP extraction and primers prediction that can be used on their Fluidigm platform. It also required implementing data correction algorithms to achieve precise genetic maps in the four crosses. The QTL detection itself required careful statistical pre-processing of phenotypic data. The authors then used a combination of several QTL detection methods, including an original meta-QTL method they developed in the software MapDisto. The authors then perform a very complete and convincing analysis of candidate genes, which includes genes already identified for a similar disease (RSV) on chromosome 11 of rice. What remains to elucidate is whether the candidate genes are actually involved or not in the disease resistance process. The team has already started implementing gene knockout strategies to study some of them in more detail. It will be interesting to see whether those genes act against the virus itself, or against the insect vector. Overall the work is of high quality and represents an important advance in the knowledge of disease resistance. In addition, it has many implications for crop breeding, allowing the setup of large-scale, marker-assisted strategies, for new resistant elite varieties of rice. References Morales F and Jennings P (2010) Rice hoja blanca: a complex plant-virus-vector pathosystem. CAB Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1079/PAVSNNR20105043 Romero LE, Lozano I, Garavito A, et al (2014) Major QTLs control resistance to Rice hoja blanca virus and its vector Tagosodes orizicolus. G3 | Genes, Genomes, Genetics 4:133–142. https://doi.org/10.1534/g3.113.009373 Silva A, Montoya ME, Quintero C, Cuasquer J, Tohme J, Graterol E, Cruz M, Lorieux M (2023) Genetic bases of resistance to the rice hoja blanca disease deciphered by a QTL approach. bioRxiv, 2022.11.07.515427, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.07.515427 | Genetic bases of resistance to the rice hoja blanca disease deciphered by a QTL approach | Alexander Silva, Maria Elker Montoya, Constanza Quintero, Juan Cuasquer, Joe Tohme, Eduardo Graterol, Maribel Cruz, Mathias Lorieux | <p style="text-align: justify;">Rice hoja blanca (RHB) is one of the most serious diseases in rice growing areas in tropical Americas. Its causal agent is Rice hoja blanca virus (RHBV), transmitted by the planthopper <em>Tagosodes orizicolus </em>... |  | Functional genomics, Plants | Olivier Panaud | 2022-11-09 09:13:30 | View | |

19 Jul 2021

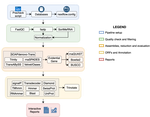

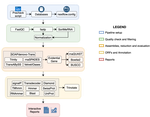

TransPi - a comprehensive TRanscriptome ANalysiS PIpeline for de novo transcriptome assemblyRamon E Rivera-Vicens, Catalina Garcia-Escudero, Nicola Conci, Michael Eitel, Gert Wörheide https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.18.431773TransPI: A balancing act between transcriptome assemblersRecommended by Oleg Simakov based on reviews by Gustavo Sanchez and Juan Daniel Montenegro CabreraEver since the introduction of the first widely usable assemblers for transcriptomic reads (Huang and Madan 1999; Schulz et al. 2012; Simpson et al. 2009; Trapnell et al. 2010, and many more), it has been a technical challenge to compare different methods and to choose the “right” or “best” assembly. It took years until the first widely accepted set of benchmarks beyond raw statistical evaluation became available (e.g., Parra, Bradnam, and Korf 2007; Simão et al. 2015). However, an approach to find the right balance between the number of transcripts or isoforms vs. evolutionary completeness measures has been lacking. This has been particularly pronounced in the field of non-model organisms (i.e., wild species that lack a genomic reference). Often, studies in this area employed only one set of assembly tools (the most often used to this day being Trinity, Haas et al. 2013; Grabherr et al. 2011). While it was relatively straightforward to obtain an initial assembly, its validation, annotation, as well its application to the particular purpose that the study was designed for (phylogenetics, differential gene expression, etc) lacked a clear workflow. This led to many studies using a custom set of tools with ensuing various degrees of reproducibility. TransPi (Rivera-Vicéns et al. 2021) fills this gap by first employing a meta approach using several available transcriptome assemblers and algorithms to produce a combined and reduced transcriptome assembly, then validating and annotating the resulting transcriptome. Notably, TransPI performs an extensive analysis/detection of chimeric transcripts, the results of which show that this new tool often produces fewer misassemblies compared to Trinity. TransPI not only generates a final report that includes the most important plots (in clickable/zoomable format) but also stores all relevant intermediate files, allowing advanced users to take a deeper look and/or experiment with different settings. As running TransPi is largely automated (including its installation via several popular package managers), it is very user-friendly and is likely to become the new "gold standard" for transcriptome analyses, especially of non-model organisms. References Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, Amit I, Adiconis X, Fan L, Raychowdhury R, Zeng Q, Chen Z, Mauceli E, Hacohen N, Gnirke A, Rhind N, di Palma F, Birren BW, Nusbaum C, Lindblad-Toh K, Friedman N, Regev A (2011) Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nature Biotechnology, 29, 644–652. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.1883 Haas BJ, Papanicolaou A, Yassour M, Grabherr M, Blood PD, Bowden J, Couger MB, Eccles D, Li B, Lieber M, MacManes MD, Ott M, Orvis J, Pochet N, Strozzi F, Weeks N, Westerman R, William T, Dewey CN, Henschel R, LeDuc RD, Friedman N, Regev A (2013) De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nature Protocols, 8, 1494–1512. https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2013.084 Huang X, Madan A (1999) CAP3: A DNA Sequence Assembly Program. Genome Research, 9, 868–877. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.9.9.868 Parra G, Bradnam K, Korf I (2007) CEGMA: a pipeline to accurately annotate core genes in eukaryotic genomes. Bioinformatics, 23, 1061–1067. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btm071 Rivera-Vicéns RE, Garcia-Escudero CA, Conci N, Eitel M, Wörheide G (2021) TransPi – a comprehensive TRanscriptome ANalysiS PIpeline for de novo transcriptome assembly. bioRxiv, 2021.02.18.431773, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.18.431773 Schulz MH, Zerbino DR, Vingron M, Birney E (2012) Oases: robust de novo RNA-seq assembly across the dynamic range of expression levels. Bioinformatics, 28, 1086–1092. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bts094 Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM (2015) BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics, 31, 3210–3212. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351 Simpson JT, Wong K, Jackman SD, Schein JE, Jones SJM, Birol İ (2009) ABySS: A parallel assembler for short read sequence data. Genome Research, 19, 1117–1123. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.089532.108 Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, Salzberg SL, Wold BJ, Pachter L (2010) Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nature Biotechnology, 28, 511–515. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.1621 | TransPi - a comprehensive TRanscriptome ANalysiS PIpeline for de novo transcriptome assembly | Ramon E Rivera-Vicens, Catalina Garcia-Escudero, Nicola Conci, Michael Eitel, Gert Wörheide | <p style="text-align: justify;">The use of RNA-Seq data and the generation of de novo transcriptome assemblies have been pivotal for studies in ecology and evolution. This is distinctly true for non-model organisms, where no genome information is ... |  | Bioinformatics, Evolutionary genomics | Oleg Simakov | 2021-02-18 20:56:08 | View | |

09 Aug 2023

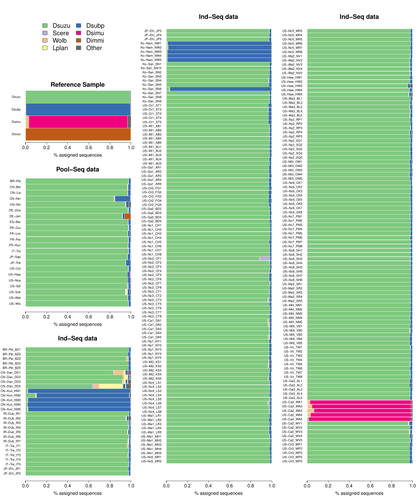

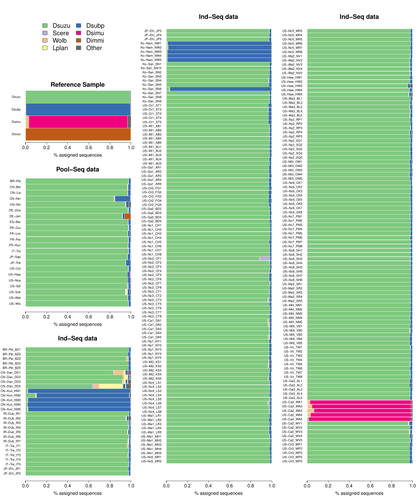

Efficient k-mer based curation of raw sequence data: application in Drosophila suzukiiGautier Mathieu https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.18.537389Decontaminating reads, not contigsRecommended by Nicolas Galtier based on reviews by Marie Cariou and Denis BaurainContamination, the presence of foreign DNA sequences in a sample of interest, is currently a major problem in genomics. Because contamination is often unavoidable at the experimental stage, it is increasingly recognized that the processing of high-throughput sequencing data must include a decontamination step. This is usually performed after the many sequence reads have been assembled into a relatively small number of contigs. Dubious contigs are then discarded based on their composition (e.g. GC-content) or because they are highly similar to a known piece of DNA from a foreign species. Here [1], Mathieu Gautier explores a novel strategy consisting in decontaminating reads, not contigs. Why is this promising? Assembly programs and algorithms are complex, and it is not easy to predict, or monitor, how they handle contaminant reads. Ideally, contaminant reads will be assembled into obvious contaminant contigs. However, there might be more complex situations, such as chimeric contigs with alternating genuine and contaminant segments. Decontaminating at the read level, if possible, should eliminate such unfavorable situations where sequence information from contaminant and target samples are intimately intertwined by an assembler. To achieve this aim, Gautier proposes to use methods initially designed for the analysis of metagenomic data. This is pertinent since the decontamination process involves considering a sample as a mixture of different sources of DNA. The programs used here, CLARK and CLARK-L, are based on so-called k-mer analysis, meaning that the similarity between a read to annotate and a reference sequence is measured by how many sub-sequences (of length 31 base pairs for CLARK and 27 base pairs for CLARK-L) they share. This is notoriously more efficient than traditional sequence alignment algorithms when it comes to comparing a very large number of (most often unrelated) sequences. This is, therefore, a reference-based approach, in which the reads from a sample are assigned to previously sequenced genomes based on k-mer content. This original approach is here specifically applied to the case of Drosophila suzukii, an invasive pest damaging fruit production in Europe and America. Fortunately, Drosophila is a genus of insects with abundant genomic resources, including high-quality reference genomes in dozens of species. Having calibrated and validated his pipeline using data sets of known origins, Gautier quantifies in each of 258 presumed D. suzukii samples the proportion of reads that likely belong to other species of fruit flies, or to fruit fly-associated microbes. This proportion is close to one in 16 samples, which clearly correspond to mis-labelled individuals. It is non-negligible in another ~10 samples, which really correspond to D. suzukii individuals. Most of these reads of unexpected origin are contaminants and should be filtered out. Interestingly, one D. suzukii sample contains a substantial proportion of reads from the closely related D. subpulchera, which might instead reflect a recent episode of gene flow between these two species. The approach, therefore, not only serves as a crucial technical step, but also has the potential to reveal biological processes. Gautier's thorough, well-documented work will clearly benefit the ongoing and future research on D. suzuki, and Drosophila genomics in general. The author and reviewers rightfully note that, like any reference-based approach, this method is heavily dependent on the availability and quality of reference genomes - Drosophila being a favorable case. Building the reference database is a key step, and the interpretation of the output can only be made in the light of its content and gaps, as illustrated by Gautier's careful and detailed discussion of his numerous results. This pioneering study is a striking demonstration of the potential of metagenomic methods for the decontamination of high-throughput sequence data at the read level. The pipeline requires remarkably few computing resources, ensuring low carbon emission. I am looking forward to seeing it applied to a wide range of taxa and samples.

Reference [1] Gautier Mathieu. Efficient k-mer based curation of raw sequence data: application in Drosophila suzukii. bioRxiv, 2023.04.18.537389, ver. 2, peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.18.537389 | Efficient k-mer based curation of raw sequence data: application in *Drosophila suzukii* | Gautier Mathieu | <p>Several studies have highlighted the presence of contaminated entries in public sequence repositories, calling for special attention to the associated metadata. Here, we propose and evaluate a fast and efficient kmer-based approach to assess th... |  | Bioinformatics, Population genomics | Nicolas Galtier | 2023-04-20 22:05:13 | View | |

08 Nov 2022

Somatic mutation detection: a critical evaluation through simulations and reanalyses in oaksSylvain Schmitt, Thibault Leroy, Myriam Heuertz, Niklas Tysklind https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.11.462798How to best call the somatic mosaic tree?Recommended by Nicolas Bierne based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersAny multicellular organism is a molecular mosaic with some somatic mutations accumulated between cell lineages. Big long-lived trees have nourished this imaginary of a somatic mosaic tree, from the observation of spectacular phenotypic mosaics and also because somatic mutations are expected to potentially be passed on to gametes in plants (review in Schoen and Schultz 2019). The lower cost of genome sequencing now offers the opportunity to tackle the issue and identify somatic mutations in trees. However, when it comes to characterizing this somatic mosaic from genome sequences, things become much more difficult than one would think in the first place. What separates cell lineages ontogenetically, in cell division number, or in time? How to sample clonal cell populations? How do somatic mutations distribute in a population of cells in an organ or an organ sample? Should they be fixed heterozygotes in the sample of cells sequenced or be polymorphic? Do we indeed expect somatic mutations to be fixed? How should we identify and count somatic mutations? To date, the detection of somatic mutations has mostly been done with a single variant caller in a given study, and we have little perspective on how different callers provide similar or different results. Some studies have used standard SNP callers that assumed a somatic mutation is fixed at the heterozygous state in the sample of cells, with an expected allele coverage ratio of 0.5, and less have used cancer callers, designed to detect mutations in a fraction of the cells in the sample. However, standard SNP callers detect mutations that deviate from a balanced allelic coverage, and different cancer callers can have different characteristics that should affect their outcomes. In order to tackle these issues, Schmitt et al. (2022) conducted an extensive simulation analysis to compare different variant callers. Then, they reanalyzed two large published datasets on pedunculate oak, Quercus robur. The analysis of in silico somatic mutations allowed the authors to evaluate the performance of different variant callers as a function of the allelic fraction of somatic mutations and the sequencing depth. They found one of the seven callers to provide better and more robust calls for a broad set of allelic fractions and sequencing depths. The reanalysis of published datasets in oaks with the most effective cancer caller of the in silico analysis allowed them to identify numerous low-frequency mutations that were missed in the original studies. I recommend the study of Schmitt et al. (2022) first because it shows the benefit of using cancer callers in the study of somatic mutations, whatever the allelic fraction you are interested in at the end. You can select fixed heterozygotes if this is your ultimate target, but cancer callers allow you to have in addition a valuable overview of the allelic fractions of somatic mutations in your sample, and most do as well as SNP callers for fixed heterozygous mutations. In addition, Schmitt et al. (2022) provide the pipelines that allow investigating in silico data that should correspond to a given study design, encouraging to compare different variant callers rather than arbitrarily going with only one. We can anticipate that the study of somatic mutations in non-model species will increasingly attract attention now that multiple tissues of the same individual can be sequenced at low cost, and the study of Schmitt et al. (2022) paves the way for questioning and choosing the best variant caller for the question one wants to address. References Schoen DJ, Schultz ST (2019) Somatic Mutation and Evolution in Plants. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 50, 49–73. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110218-024955 Schmitt S, Leroy T, Heuertz M, Tysklind N (2022) Somatic mutation detection: a critical evaluation through simulations and reanalyses in oaks. bioRxiv, 2021.10.11.462798. ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.11.462798 | Somatic mutation detection: a critical evaluation through simulations and reanalyses in oaks | Sylvain Schmitt, Thibault Leroy, Myriam Heuertz, Niklas Tysklind | <p style="text-align: justify;">1. Mutation, the source of genetic diversity, is the raw material of evolution; however, the mutation process remains understudied, especially in plants. Using both a simulation and reanalysis framework, we set out ... |  | Bioinformatics, Plants | Nicolas Bierne | Anonymous, Anonymous | 2022-04-28 13:24:19 | View |

12 Jul 2022

Chromosome-level genome assembly and annotation of two lineages of the ant Cataglyphis hispanica: steppingstones towards genomic studies of hybridogenesis and thermal adaptation in desert antsHugo Darras, Natalia de Souza Araujo, Lyam Baudry, Nadège Guiglielmoni, Pedro Lorite, Martial Marbouty, Fernando Rodriguez, Irina Arkhipova, Romain Koszul, Jean-François Flot, Serge Aron https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.07.475286A genomic resource for ants, and moreRecommended by Nadia Ponts based on reviews by Isabel Almudi and Nicolas NègreThe ant species Cataglyphis hispanica is remarkably well adapted to arid habitats of the Iberian Peninsula where two hybridogenetic lineages co-occur, i.e., queens mating with males from the other lineage produce only non-reproductive hybrid workers whereas reproductive males and females are produced by parthenogenesis (Lavanchy and Schwander, 2019). For these two reasons, the genomes of these lineages, Chis1 and Chis2, are potential gold mines to explore the genetic bases of thermal adaptation and the evolution of alternative reproductive modes. Nowadays, sequencing technology enables assembling all kinds of genomes provided genomic DNA can be extracted. More difficult to achieve is high-quality assemblies with just as high-quality annotations that are readily available to the community to be used and re-used at will (Byrne et al., 2019; Salzberg, 2019). The challenge was successfully completed by Darras and colleagues, the generated resource being fully available to the community, including scripts and command lines used to obtain the proposed results. The authors particularly describe that lineage Chis2 has 27 chromosomes, against 26 or 27 for lineage Chis1, with a Robertsonian translocation identified by chromosome conformation capture (Duan et al., 2010, 2012) in the two Queens sequenced. Transcript-supported gene annotation provided 11,290 high-quality gene models. In addition, an ant-tailored annotation pipeline identified 56 different families of repetitive elements in both Chis1 and Chis2 lineages of C. hispanica spread in a little over 15 % of the genome. Altogether, the genomes of Chis1 and Chis2 are highly similar and syntenic, with some level of polymorphism raising questions about their evolutionary story timeline. In particular, the uniform distribution of polymorphisms along the genomes shakes up a previous hypothesis of hybridogenetic lineage pairs determined by ancient non-recombining regions (Linksvayer, Busch and Smith, 2013). I recommend this paper because the science behind is both solid and well-explained. The provided resource is of high quality, and accompanied by a critical exploration of the perspectives brought by the results. These genomes are excellent resources to now go further in exploring the possible events at the genome level that accompanied the remarkable thermal adaptation of the ants Cataglyphis, as well as insights into the genetics of hybridogenetic lineages. Beyond the scientific value of the resources and insights provided by the work performed, I also recommend this article because it is an excellent example of Open Science (Allen and Mehler, 2019; Sarabipour et al., 2019), all data methods and tools being fully and easily accessible to whoever wants/needs it. References Allen C, Mehler DMA (2019) Open science challenges, benefits and tips in early career and beyond. PLOS Biology, 17, e3000246. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000246 Byrne A, Cole C, Volden R, Vollmers C (2019) Realizing the potential of full-length transcriptome sequencing. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 374, 20190097. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0097 Darras H, de Souza Araujo N, Baudry L, Guiglielmoni N, Lorite P, Marbouty M, Rodriguez F, Arkhipova I, Koszul R, Flot J-F, Aron S (2022) Chromosome-level genome assembly and annotation of two lineages of the ant Cataglyphis hispanica: stepping stones towards genomic studies of hybridogenesis and thermal adaptation in desert ants. bioRxiv, 2022.01.07.475286, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.07.475286 Duan Z, Andronescu M, Schutz K, Lee C, Shendure J, Fields S, Noble WS, Anthony Blau C (2012) A genome-wide 3C-method for characterizing the three-dimensional architectures of genomes. Methods, 58, 277–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.06.018 Duan Z, Andronescu M, Schutz K, McIlwain S, Kim YJ, Lee C, Shendure J, Fields S, Blau CA, Noble WS (2010) A three-dimensional model of the yeast genome. Nature, 465, 363–367. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08973 Lavanchy G, Schwander T (2019) Hybridogenesis. Current Biology, 29, R9–R11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2018.11.046 Linksvayer TA, Busch JW, Smith CR (2013) Social supergenes of superorganisms: Do supergenes play important roles in social evolution? BioEssays, 35, 683–689. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.201300038 Salzberg SL (2019) Next-generation genome annotation: we still struggle to get it right. Genome Biology, 20, 92. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-019-1715-2 Sarabipour S, Debat HJ, Emmott E, Burgess SJ, Schwessinger B, Hensel Z (2019) On the value of preprints: An early career researcher perspective. PLOS Biology, 17, e3000151. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000151 | Chromosome-level genome assembly and annotation of two lineages of the ant Cataglyphis hispanica: steppingstones towards genomic studies of hybridogenesis and thermal adaptation in desert ants | Hugo Darras, Natalia de Souza Araujo, Lyam Baudry, Nadège Guiglielmoni, Pedro Lorite, Martial Marbouty, Fernando Rodriguez, Irina Arkhipova, Romain Koszul, Jean-François Flot, Serge Aron | <p style="text-align: justify;"><em>Cataglyphis</em> are thermophilic ants that forage during the day when temperatures are highest and sometimes close to their critical thermal limit. Several Cataglyphis species have evolved unusual reproductive ... |  | Evolutionary genomics | Nadia Ponts | Nicolas Nègre, Isabel Almudi | 2022-01-13 16:47:30 | View |