Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract▼ | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

01 May 2024

Evolution of ion channels in cetaceans: A natural experiment in the tree of lifeCristóbal Uribe, Mariana F. Nery, Kattina Zavala, Gonzalo A. Mardones, Gonzalo Riadi & Juan C. Opazo https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.06.15.545160v8Positive selection acted upon cetacean ion channels during the aquatic transitionRecommended by Gavin Douglas based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

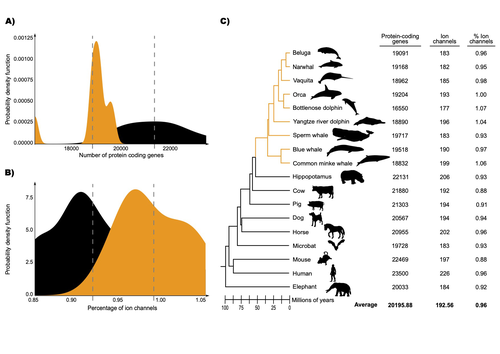

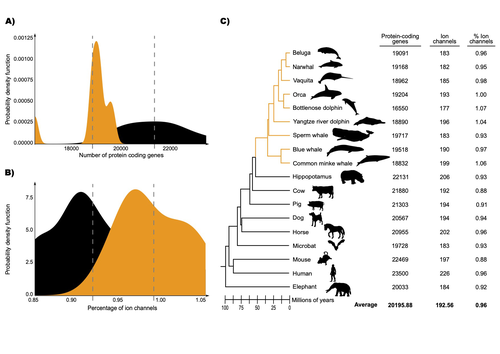

The transition of cetaceans (whales, dolphins, and porpoises) from terrestrial to aquatic lifestyles is a striking example of natural selection driving major phenotypic changes (Figure 1). For instance, cetaceans have evolved the ability to withstand high pressure and to store oxygen for long periods, among other adaptations (Das et al. 2023). Many phenotypic changes, such as shifts in organ structure, have been well-characterized through fossils (Thewissen et al. 2009). Although such phenotypic transitions are now well understood, we have only a partial understanding of the underlying genetic mechanisms. Scanning for signatures of adaptation in genes related to phenotypes of interest is one approach to better understand these mechanisms. This was the focus of Uribe and colleagues’ (2024) work, who tested for such signatures across cetacean protein-coding genes.

Figure 1: The skeletons of Ambulocetus (an early whale; top) and Pakicetus (the earliest known cetacean, which lived about 50 million years ago; bottom). Copyright: J. G. M. Thewissen. Displayed here with permission from the copyright holder.

The authors were specifically interested in investigating the evolution of ion channels, as these proteins play fundamental roles in physiological processes. An important aspect of their work was to develop a bioinformatic pipeline to identify orthologous ion channel genes across a set of genomes. After applying their bioinformatic workflow to 18 mammalian species (including nine cetaceans), they conducted tests to find out whether these genes showed signatures of positive selection in the cetacean lineage. For many ion channel genes, elevated ratios of non-synonymous to synonymous substitution rates were detected (for at least a subset of sites, and not necessarily the entire coding region of the genes). The genes concerned were enriched for several functions, including heart and nervous system-related phenotypes. One top gene hit among the putatively selected genes was SCN5A, which encodes a sodium channel expressed in the heart. Interestingly, the authors noted a specific amino acid replacement, which is associated with sensitivity to the toxin tetrodotoxin in other lineages. This substitution appears to have occurred in the common ancestor of toothed whales, and then was reversed in the ancestor of bottlenose dolphins. The authors describe known bottlenose dolphin interactions with toxin-producing pufferfish that could result in high tetrodotoxin exposure, and thus perhaps higher selection for tetrodotoxin resistance. Although this observation is intriguing, the authors emphasize it requires experimental confirmation. The authors also recapitulated the previously described observation (Yim et al. 2014; Huelsmann et al. 2019) that cetaceans have fewer protein-coding genes compared to terrestrial mammals, on average. This signal has previously been hypothesized to partially reflect adaptive gene loss. For example, specific gene loss events likely decreased the risk of developing blood clots while diving (Huelsmann et al. 2019). Uribe and colleagues also considered overall gene turnover rate, which encompasses gene copy number variation across lineages, and found the cetacean gene turnover rate to be three times higher than that of terrestrial mammals. Finally, they found that cetaceans have a higher proportion of ion channel genes (relative to all protein-coding genes in a genome) compared to terrestrial mammals. Similar investigations of the relative non-synonymous to synonymous substitution rates across cetacean and terrestrial mammal orthologs have been conducted previously, but these have primarily focused on dolphins as the sole cetacean representative (McGowen et al. 2012; Nery et al. 2013; Sun et al. 2013). These projects have also been conducted across a large proportion of orthologous genes, rather than a subset with a particular function. Performing proteome-wide investigations can be valuable in that they summarize the genome-wide signal, but can suffer from a high multiple testing burden. More generally, investigating a more targeted question, such as the extent of positive selection acting on ion channels in this case, or on genes potentially linked to cetaceans’ increased brain sizes (McGowen et al. 2011) or hypoxia tolerance (Tian et al. 2016), can be easier to interpret, as opposed to summarizing broader signals. However, these smaller-scale studies can also experience a high multiple testing burden, especially as similar tests are conducted across numerous studies, which often is not accounted for (Ioannidis 2005). In addition, integrating signals across the entire genome will ultimately be needed given that many genetic changes undoubtedly underlie cetaceans’ phenotypic diversification. As highlighted by the fact that past genome-wide analyses have produced some differing biological interpretations (McGowen et al. 2012; Nery et al. 2013; Sun et al. 2013), this is not a trivial undertaking. Nonetheless, the work performed in this preprint, and in related research, is valuable for (at least) three reasons. First, although it is a challenging task, a better understanding of the genetic basis of cetacean phenotypes could have benefits for many aspects of cetacean biology, including conservation efforts. In addition, the remarkable phenotypic shifts in cetaceans make the question of what genetic mechanisms underlie these changes intrinsically interesting to a wide audience. Last, since the cetacean fossil record is especially well-documented (Thewissen et al. 2009), cetaceans represent an appealing system to validate and further develop statistical methods for inferring adaptation from genetic data. Uribe and colleagues’ (2024) analyses provide useful insights relevant to each of these points, and have generated intriguing hypotheses for further investigation.

Das, K., Sköld, H., Lorenz, A., Parmentier, E. 2023. Who are the marine mammals? In: “Marine Mammals: A Deep Dive into the World of Science”. Brennecke, D., Knickmeier, K., Pawliczka, I., Siebert, U., Wahlberg, M (editors). Springer, Cham. p. 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-06836-2_1 Huelsmann, M., Hecker, N., Springer, M., S., Gatesy, J., Sharma, V., Hiller, M. 2019. Genes lost during the transition from land to water in cetaceans highlight genomic changes associated with aquatic adaptations. Science Advances. 5(9):eaaw6671. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aaw6671 Ioannidis, J., P., A. 2005. Why most published research findings are false. PLOS Medicine. 2(8):e124. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124 McGowen MR, Montgomery SH, Clark C, Gatesy J. 2011. Phylogeny and adaptive evolution of the brain-development gene microcephalin (MCPH1) in cetaceans. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 11(1):98. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-11-98 McGowen MR, Grossman LI, Wildman DE. 2012. Dolphin genome provides evidence for adaptive evolution of nervous system genes and a molecular rate slowdown. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 279(1743):3643–3651. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.0869 Nery, M., F., González, D., J., Opazo, J., C. 2013. How to make a dolphin: molecular signature of positive selection in cetacean genome. PLOS ONE. 8(6):e65491. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0065491 Sun, Y.-B., Zhou, W.-P., Liu, H.-Q., Irwin, D., M., Shen, Y.-Y., Zhang, Y.-P. 2013. Genome-wide scans for candidate genes involved in the aquatic adaptation of dolphins. Genome Biology and Evolution. 5(1):130–139. https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evs123 Tian, R., Wang, Z., Niu, X., Zhou, K., Xu, S., Yang, G. 2016. Evolutionary genetics of hypoxia tolerance in cetaceans during diving. Genome Biology and Evolution. 8(3):827–839. https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evw037 Thewissen, J., G., M., Cooper, L., N., George, J., C., Bajpai, S. 2009. From land to water: the origin of whales, dolphins, and porpoises. Evolution: Education and Outreach. 2(2):272–288. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12052-009-0135-2 Uribe, C., Nery, M., Zavala, K., Mardones, G., Riadi, G., Opazo, J. 2024. Evolution of ion channels in cetaceans: A natural experiment in the tree of life. bioRxiv, ver. 8 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.15.545160 Yim, H.-S., Cho, Y., S., Guang, X., Kang, S., G., Jeong, J.-Y., Cha, S.-S., Oh, H.-M., Lee, J.-H., Yang, E., C., Kwon, K., K., et al. 2014. Minke whale genome and aquatic adaptation in cetaceans. Nature Genetics. 46(1):88–92. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2835

| Evolution of ion channels in cetaceans: A natural experiment in the tree of life | Cristóbal Uribe, Mariana F. Nery, Kattina Zavala, Gonzalo A. Mardones, Gonzalo Riadi & Juan C. Opazo | <p>Cetaceans could be seen as a natural experiment within the tree of life in which a mammalian lineage changed from terrestrial to aquatic habitats. This shift involved extensive phenotypic modifications, which represent an opportunity to explore... |  | Evolutionary genomics | Gavin Douglas | 2023-07-04 20:53:46 | View | |

06 Feb 2024

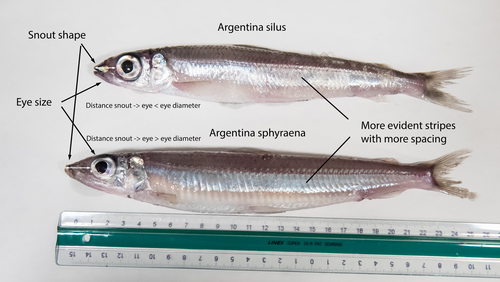

The need of decoding life for taking care of biodiversity and the sustainable use of nature in the Anthropocene - a Faroese perspectiveSvein-Ole Mikalsen, Jari í Hjøllum, Ian Salter, Anni Djurhuus, Sunnvør í Kongsstovu https://doi.org/10.32942/X21S4CWhy sequence everything? A raison d’être for the Genome Atlas of Faroese EcologyRecommended by Stephen Richards based on reviews by Tereza Manousaki and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Tereza Manousaki and 1 anonymous reviewer

When discussing the Earth BioGenome Project with scientists and potential funding agencies, one common question is: why sequence everything? Whether sequencing a subset would be more optimal is not an unreasonable question given what we know about the mathematics of importance and Pareto’s 80:20 principle, that 80% of the benefits can come from 20% of the effort. However, one must remember that this principle is an observation made in hindsight and selecting the most effective 20% of experiments is difficult. As an example, few saw great applied value in comparative genomic analysis of the archaea Haloferax mediterranei, but this enabled the discovery of CRISPR/Cas9 technology (1). When discussing whether or not to sequence all life on our planet, smaller countries such as the Faroe Islands are seldom mentioned.

1 Mojica, F. J., Díez-Villaseñor, C. S., García-Martínez, J. & Soria, E. Intervening sequences of regularly spaced prokaryotic repeats derive from foreign genetic elements. J Mol Evol 60, 174-182 (2005). 2 Mikalsen, S-O., Hjøllum, J. í., Salter, I., Djurhuus, A. & Kongsstovu, S. í. The need of decoding life for taking care of biodiversity and the sustainable use of nature in the Anthropocene – a Faroese perspective. EcoEvoRxiv (2024), ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.32942/X21S4C | The need of decoding life for taking care of biodiversity and the sustainable use of nature in the Anthropocene - a Faroese perspective | Svein-Ole Mikalsen, Jari í Hjøllum, Ian Salter, Anni Djurhuus, Sunnvør í Kongsstovu | <p>Biodiversity is under pressure, mainly due to human activities and climate change. At the international policy level, it is now recognised that genetic diversity is an important part of biodiversity. The availability of high-quality reference g... |  | ERGA, ERGA Pilot, Population genomics, Vertebrates | Stephen Richards | 2023-07-31 16:59:33 | View | |

06 Apr 2021

Evidence for shared ancestry between Actinobacteria and Firmicutes bacteriophagesMatthew Koert, Júlia López-Pérez, Courtney Mattson, Steven M. Caruso, Ivan Erill https://doi.org/10.1101/842583Viruses of bacteria: phages evolution across phylum boundariesRecommended by Denis Tagu based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersBacteria and phages have coexisted and coevolved for a long time. Phages are bacteria-infecting viruses, with a symbiotic status sensu lato, meaning they can be pathogenic, commensal or mutualistic. Thus, the association between bacteria phages has probably played a key role in the high adaptability of bacteria to most - if not all – of Earth’s ecosystems, including other living organisms (such as eukaryotes), and also regulate bacterial community size (for instance during bacterial blooms). As genetic entities, phages are submitted to mutations and natural selection, which changes their DNA sequence. Therefore, comparative genomic analyses of contemporary phages can be useful to understand their evolutionary dynamics. International initiatives such as SEA-PHAGES have started to tackle the issue of history of phage-bacteria interactions and to describe the dynamics of the co-evolution between bacterial hosts and their associated viruses. Indeed, the understanding of this cross-talk has many potential implications in terms of health and agriculture, among others. The work of Koert et al. (2021) deals with one of the largest groups of bacteria (Actinobacteria), which are Gram-positive bacteria mainly found in soil and water. Some soil-born Actinobacteria develop filamentous structures reminiscent of the mycelium of eukaryotic fungi. In this study, the authors focused on the Streptomyces clade, a large genus of Actinobacteria colonized by phages known for their high level of genetic diversity. The authors tested the hypothesis that large exchanges of genetic material occurred between Streptomyces and diverse phages associated with bacterial hosts. Using public datasets, their comparative phylogenomic analyses identified a new cluster among Actinobacteria–infecting phages closely related to phages of Firmicutes. Moreover, the GC content and codon-usage biases of this group of phages of Actinobacteria are similar to those of Firmicutes. This work demonstrates for the first time the transfer of a bacteriophage lineage from one bacterial phylum to another one. The results presented here suggest that the age of the described transfer is probably recent since several genomic characteristics of the phage are not fully adapted to their new hosts. However, the frequency of such transfer events remains an open question. If frequent, such exchanges would mean that pools of bacteriophages are regularly fueled by genetic material coming from external sources, which would have important implications for the co-evolutionary dynamics of phages and bacteria. References Koert, M., López-Pérez, J., Courtney Mattson, C., Caruso, S. and Erill, I. (2021) Evidence for shared ancestry between Actinobacteria and Firmicutes bacteriophages. bioRxiv, 842583, version 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Genomics. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/842583 | Evidence for shared ancestry between Actinobacteria and Firmicutes bacteriophages | Matthew Koert, Júlia López-Pérez, Courtney Mattson, Steven M. Caruso, Ivan Erill | <p>Bacteriophages typically infect a small set of related bacterial strains. The transfer of bacteriophages between more distant clades of bacteria has often been postulated, but remains mostly unaddressed. In this work we leverage the sequencing ... |  | Evolutionary genomics | Denis Tagu | 2019-12-10 15:26:31 | View | |

15 Mar 2024

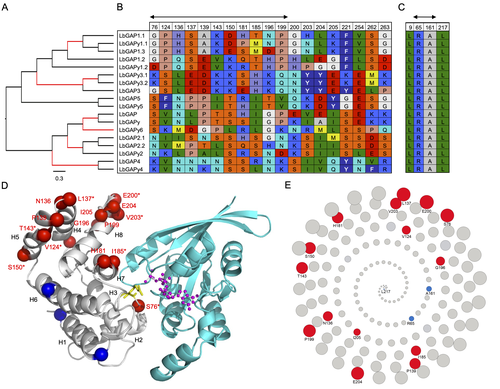

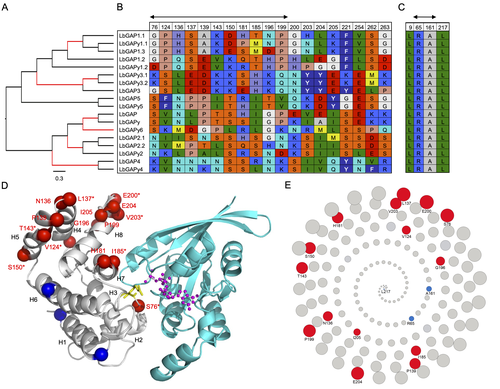

Convergent origin and accelerated evolution of vesicle-associated RhoGAP proteins in two unrelated parasitoid waspsDominique Colinet, Fanny Cavigliasso, Matthieu Leobold, Appoline Pichon, Serge Urbach, Dominique Cazes, Marine Poullet, Maya Belghazi, Anne-Nathalie Volkoff, Jean-Michel Drezen, Jean-Luc Gatti, and Marylène Poirié https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.05.543686Using transcriptomics and proteomics to understand the expansion of a secreted poisonous armoury in parasitoid wasps genomesRecommended by Ignacio Bravo based on reviews by Inacio Azevedo and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Inacio Azevedo and 2 anonymous reviewers

Parasitoid wasps lay their eggs inside another arthropod, whose body is physically consumed by the parasitoid larvae. Phylogenetic inference suggests that Parasitoida are monophyletic, and that this clade underwent a strong radiation shortly after branching off from the Apocrita stem, some 236 million years ago (Peters et al. 2017). The increase in taxonomic diversity during evolutionary radiations is usually concurrent with an increase in genetic/genomic diversity, and is often associated with an increase in phenotypic diversity. Gene (or genome) duplication provides the evolutionary potential for such increase of genomic diversity by neo/subfunctionalisation of one of the gene paralogs, and is often proposed to be related to evolutionary radiations (Ohno 1970; Francino 2005).

References

| Convergent origin and accelerated evolution of vesicle-associated RhoGAP proteins in two unrelated parasitoid wasps | Dominique Colinet, Fanny Cavigliasso, Matthieu Leobold, Appoline Pichon, Serge Urbach, Dominique Cazes, Marine Poullet, Maya Belghazi, Anne-Nathalie Volkoff, Jean-Michel Drezen, Jean-Luc Gatti, and Marylène Poirié | <p>Animal venoms and other protein-based secretions that perform a variety of functions, from predation to defense, are highly complex cocktails of bioactive compounds. Gene duplication, accompanied by modification of the expression and/or functio... |  | Evolutionary genomics | Ignacio Bravo | 2023-06-12 11:08:31 | View | |

16 Dec 2022

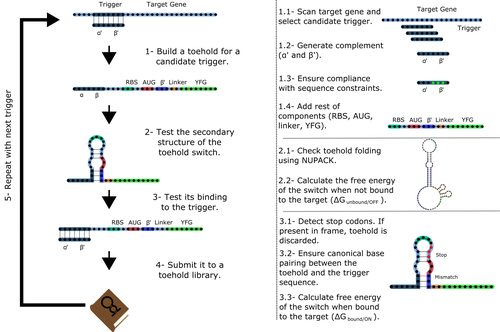

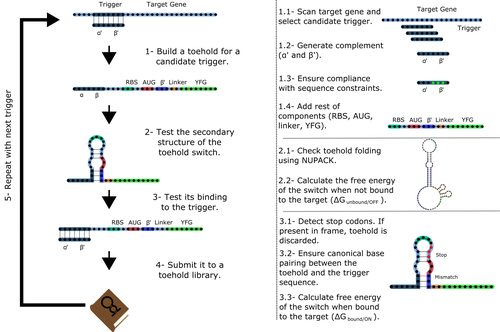

Toeholder: a Software for Automated Design and In Silico Validation of Toehold RiboswitchesAngel F. Cisneros, François D. Rouleau, Carla Bautista, Pascale Lemieux, Nathan Dumont-Leblond https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.09.467922A novel approach for engineering biological systems by interfacing computer science with synthetic biologyRecommended by Sahar Melamed based on reviews by Wim Wranken and 1 anonymous reviewerBiological systems depend on finely tuned interactions of their components. Thus, regulating these components is critical for the system's functionality. In prokaryotic cells, riboswitches are regulatory elements controlling transcription or translation. Riboswitches are RNA molecules that are usually located in the 5′-untranslated region of protein-coding genes. They generate secondary structures leading to the regulation of the expression of the downstream protein-coding gene (Kavita and Breaker, 2022). Riboswitches are very versatile and can bind a wide range of small molecules; in many cases, these are metabolic byproducts from the gene’s enzymatic or signaling pathway. Their versatility and abundance in many species make them attractive for synthetic biological circuits. One class that has been drawing the attention of synthetic biologists is toehold switches (Ekdahl et al., 2022; Green et al., 2014). These are single-stranded RNA molecules harboring the necessary elements for translation initiation of the downstream gene: a ribosome-binding site and a start codon. Conformation change of toehold switches is triggered by an RNA molecule, which enables translation. To exploit the most out of toehold switches, automation of their design would be highly advantageous. Cisneros and colleagues (Cisneros et al., 2022) developed a tool, “Toeholder”, that automates the design of toehold switches and performs in silico tests to select switch candidates for a target gene. Toeholder is an open-source tool that provides a comprehensive and automated workflow for the design of toehold switches. While web tools have been developed for designing toehold switches (To et al., 2018), Toeholder represents an intriguing approach to engineering biological systems by coupling synthetic biology with computational biology. Using molecular dynamics simulations, it identified the positions in the toehold switch where hydrogen bonds fluctuate the most. Identifying these regions holds great potential for modifications when refining the design of the riboswitches. To be effective, toehold switches should provide a strong ON signal and a weak OFF signal in the presence or the absence of a target, respectively. Toeholder nicely ranks the candidate toehold switches based on experimental evidence that correlates with toehold performance (based on good ON/OFF ratios). Riboswitches are highly appealing for a broad range of applications, including pharmaceutical and medical purposes (Blount and Breaker, 2006; Giarimoglou et al., 2022; Tickner and Farzan, 2021), thanks to their adaptability and inexpensiveness. The Toeholder tool developed by Cisneros and colleagues is expected to promote the implementation of toehold switches into these various applications. References Blount KF, Breaker RR (2006) Riboswitches as antibacterial drug targets. Nature Biotechnology, 24, 1558–1564. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt1268 Cisneros AF, Rouleau FD, Bautista C, Lemieux P, Dumont-Leblond N, ULaval 2019 T iGEM (2022) Toeholder: a Software for Automated Design and In Silico Validation of Toehold Riboswitches. bioRxiv, 2021.11.09.467922, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Genomics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.09.467922 Ekdahl AM, Rojano-Nisimura AM, Contreras LM (2022) Engineering Toehold-Mediated Switches for Native RNA Detection and Regulation in Bacteria. Journal of Molecular Biology, 434, 167689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2022.167689 Giarimoglou N, Kouvela A, Maniatis A, Papakyriakou A, Zhang J, Stamatopoulou V, Stathopoulos C (2022) A Riboswitch-Driven Era of New Antibacterials. Antibiotics, 11, 1243. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11091243 Green AA, Silver PA, Collins JJ, Yin P (2014) Toehold Switches: De-Novo-Designed Regulators of Gene Expression. Cell, 159, 925–939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.002 Kavita K, Breaker RR (2022) Discovering riboswitches: the past and the future. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2022.08.009 Tickner ZJ, Farzan M (2021) Riboswitches for Controlled Expression of Therapeutic Transgenes Delivered by Adeno-Associated Viral Vectors. Pharmaceuticals, 14, 554. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14060554 To AC-Y, Chu DH-T, Wang AR, Li FC-Y, Chiu AW-O, Gao DY, Choi CHJ, Kong S-K, Chan T-F, Chan K-M, Yip KY (2018) A comprehensive web tool for toehold switch design. Bioinformatics, 34, 2862–2864. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty216 | Toeholder: a Software for Automated Design and In Silico Validation of Toehold Riboswitches | Angel F. Cisneros, François D. Rouleau, Carla Bautista, Pascale Lemieux, Nathan Dumont-Leblond | <p>Abstract: Synthetic biology aims to engineer biological circuits, which often involve gene expression. A particularly promising group of regulatory elements are riboswitches because of their versatility with respect to their targets, but e... |  | Bioinformatics | Sahar Melamed | 2022-02-16 14:40:13 | View |